It’s just a ribbon. If you glance at a Chile South America map, that’s the first thing you notice—a thin, precarious strip of land pinned between the jagged Andes and the Pacific Ocean. It looks like an afterthought. It looks like someone drew a line down the coast and just decided that everything to the left belonged to Santiago.

But honestly? That map is lying to you.

Maps are flat, and Chile is anything but. It is a vertical obsession. Stretching over 4,000 kilometers from the desert that hasn't seen rain in decades to the glacial fjords of the south, Chile is a geographical freak of nature. You can’t just look at a map of South America and "get" Chile. You have to understand how that geography dictates every single thing about the people who live there.

The Atacama: A Map of Mars on Earth

Start at the top. The northern part of the Chile South America map is dominated by the Atacama Desert. People call it the driest place on Earth, but that doesn't really capture the vibe. It’s a place where NASA tests Mars rovers because the soil chemistry is basically identical to what we find on the Red Planet.

Look at the town of San Pedro de Atacama. It’s a tiny oasis surrounded by salt flats and volcanoes. If you’re looking at a topographical map, you’ll see the "Puna de Atacama," a high-altitude plateau. It’s brutal. The air is so thin it feels like you’re breathing through a straw, and the sun is so intense it feels personal.

Experts like Dr. Chris McKay from NASA’s Ames Research Center have spent years studying this specific patch of the map because it’s the closest thing we have to an alien world. There are spots in the Atacama where rain has never been recorded in human history. Not once. Yet, when you zoom into the map, you see these ancient geoglyphs—huge drawings in the sand like the "Gigante de Atacama"—left by cultures that somehow thrived in this impossible dryness.

Why the Middle is Where the Heart Is

Most people live in the middle. If you look at a population density overlay on a Chile South America map, there’s a massive bulge around Santiago and Valparaíso. This is the Mediterranean zone. It’s weirdly similar to California or central Italy.

✨ Don't miss: Things to do in Hanover PA: Why This Snack Capital is More Than Just Pretzels

This is where the wine comes from.

If you’re driving through the Maipo or Colchagua valleys, the map shows a narrow corridor. To your right, the Andes are a constant, looming wall of granite. To your left, the Coastal Range (Cordillera de la Costa) keeps the ocean mist at bay. This creates a "closet" effect where the climate is perfectly regulated. It’s why Chilean Cabernet is famous globally; the geography acts like a natural greenhouse.

But here’s the thing: Santiago is a basin. Because of how it sits on the map—trapped between two mountain ranges—the city struggles with "thermal inversion." Basically, the smog gets stuck. In the winter, the map looks beautiful with snow-capped peaks, but the air quality can be rough. It’s the price you pay for living in one of the most dramatically situated capitals in the world.

The Shattered South: Where the Map Breaks

Go south of the Biobío River, and the Chile South America map starts to fall apart. Literally. The solid coastline of the north and center dissolves into a chaotic mess of islands, channels, and peninsulas.

This is Patagonia.

This is where the "Carretera Austral" lives. It’s a road that shouldn’t exist. Pinochet started building it in the 70s for strategic reasons, but it’s basically a 1,200-kilometer engineering nightmare through rainforests and over glaciers. When you look at the map of the Aysén region, you realize there aren't many roads. Most travel happens by ferry.

🔗 Read more: Hotels Near University of Texas Arlington: What Most People Get Wrong

The geography here is defined by "The Big Ice." The Northern and Southern Patagonian Ice Fields are the largest masses of ice outside of the poles. If you zoom in on a satellite map of the Bernardo O'Higgins National Park, it looks like a white smear. That’s ice thousands of years old, calving into turquoise lakes.

The Myth of Chiloé

Right where the mainland starts to crumble is the island of Chiloé. It has its own culture, its own myths, and even its own map of wooden churches—some of which are UNESCO World Heritage sites. The islanders, or Chilotes, historically felt more connected to the sea than to Santiago. In fact, until the mid-1800s, they were one of the last royalist strongholds during the wars of independence. The map tells you they are part of Chile, but the spirit is almost like a separate country.

The Andes: More Than Just a Border

You can’t talk about a Chile South America map without the mountains. The Andes are the spine. They aren't just a border with Argentina; they are a psychological barrier.

Chileans often refer to their country as a "geographic island."

Bound by the desert to the north.

The ice to the south.

The ocean to the west.

The mountains to the east.

This isolation has shaped the Chilean Spanish dialect—which is fast, full of slang (chilenismos), and often barely intelligible to other Spanish speakers. It’s the language of a people who were tucked away behind a 20,000-foot wall for centuries.

Geologically, the map is a ticking time bomb. Chile sits right on the "Ring of Fire." The Nazca Plate is constantly shoving itself under the South American Plate. This is why Chile has the most powerful earthquakes ever recorded. The 1960 Valdivia earthquake was a 9.5 on the Richter scale. The map changed that day—islands sank, new ones appeared, and rivers reversed their flow.

💡 You might also like: 10 day forecast myrtle beach south carolina: Why Winter Beach Trips Hit Different

Practical Insights for Navigating the Map

If you are planning to actually use a Chile South America map for travel or business, you need to understand the scale. Chile is longer than the distance from London to Baghdad. You cannot "do" Chile in a week.

- Distrust Travel Times: A 200-mile drive in the Atacama is not the same as a 200-mile drive in Patagonia. The former is a straight line through gravel; the latter involves three ferries and a prayer.

- Fly or Die: Unless you have months, you’ll be using the "domestic bridge." Santiago’s Arturo Merino Benítez (SCL) airport is the hub. To get from the north to the south, you almost always have to fly back to Santiago first. It’s a hub-and-spoke system that reflects the centralized nature of the country.

- The "T" Zone: When looking at maps for the central region, pay attention to the "Valparaíso-Santiago-Rancagua" triangle. This is the economic engine. Outside of this, things get rural and rugged very quickly.

- Altitude Awareness: If your map shows you heading east toward the Andes, check the contour lines. Places like the El Tatio Geysers are at 4,300 meters. If you don't acclimate, the map won't matter because you'll be too sick to see the sights.

The Secret Territories

Finally, look at the bottom right and far out into the ocean. Most people forget that the Chile South America map technically extends to Antarctica. Chile claims a massive wedge of the frozen continent, though international treaties keep things complicated.

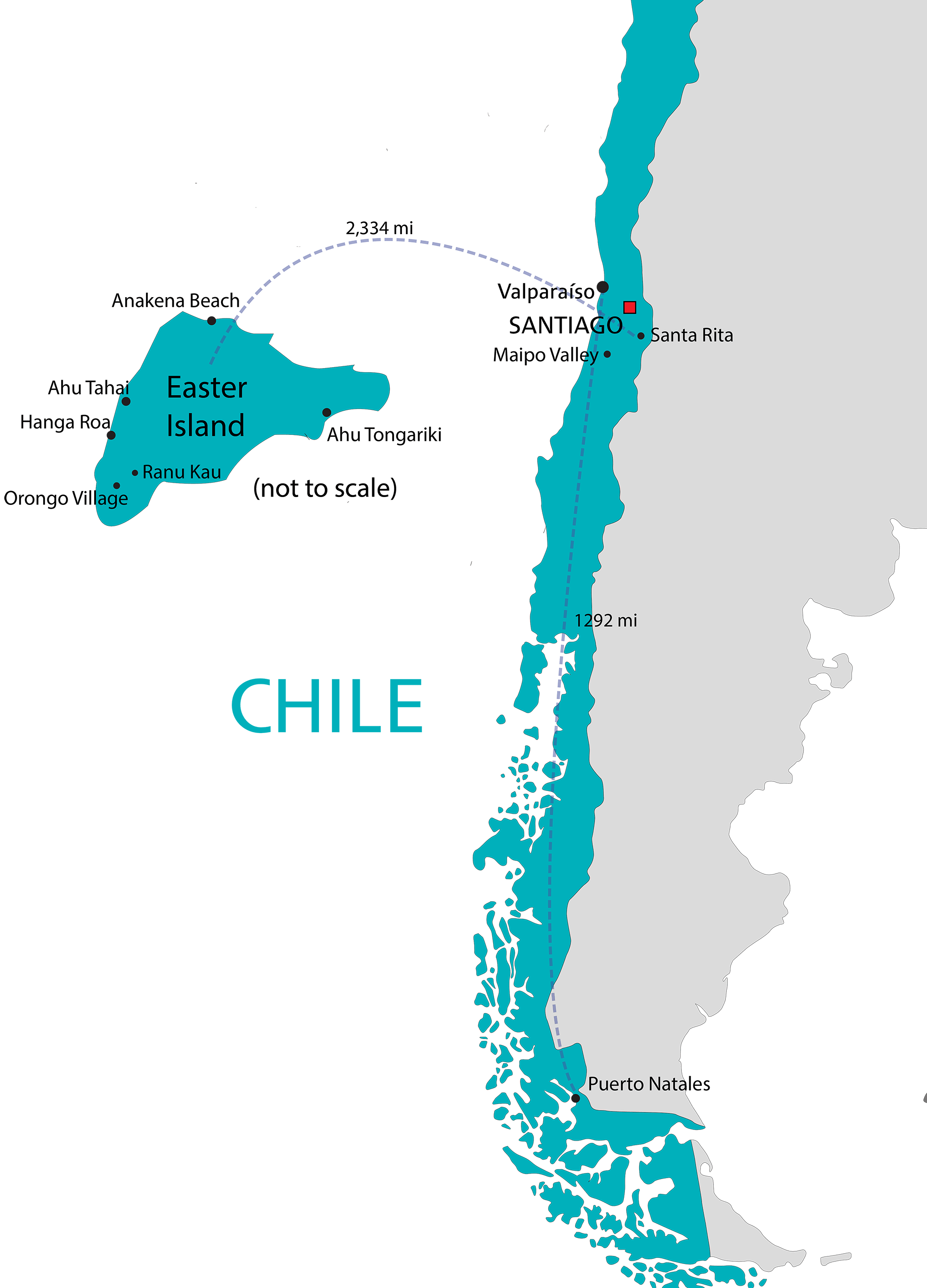

Then there’s Rapa Nui (Easter Island). It’s nearly 3,700 kilometers away from the coast. It’s just a speck on the map, a tiny volcanic triangle in the middle of the Pacific. It’s the most isolated inhabited island on the planet. Including it in the national map is a point of pride, even if it’s culturally closer to Tahiti than to Santiago.

Chile is a country of extremes that shouldn't work together, but somehow they do. It’s a geographic miracle held together by a shared sense of resilience.

Actionable Steps for Your Chilean Research

To truly understand the geography of this region, stop looking at flat 2D maps and start using 3D visualization tools.

- Use Google Earth Pro: Toggle the terrain layer to see the verticality of the Andes. It explains why some towns only a few miles apart are actually separated by a 10-hour drive.

- Check the Seismology Maps: Visit the Centro Sismológico Nacional to see a real-time map of tremors. It gives you a visceral sense of how active the land really is.

- Download Offline Maps: If you are heading to Patagonia (Magallanes or Aysén), do not rely on cellular data. The topography blocks signals, and "dead zones" cover about 80% of the southern hiking trails.

- Verify Border Crossings: If your map shows a road into Argentina, verify if the pass is open. High-altitude passes like Paso Los Libertadores close frequently in winter due to snow, rendering the map useless for cross-border travel.