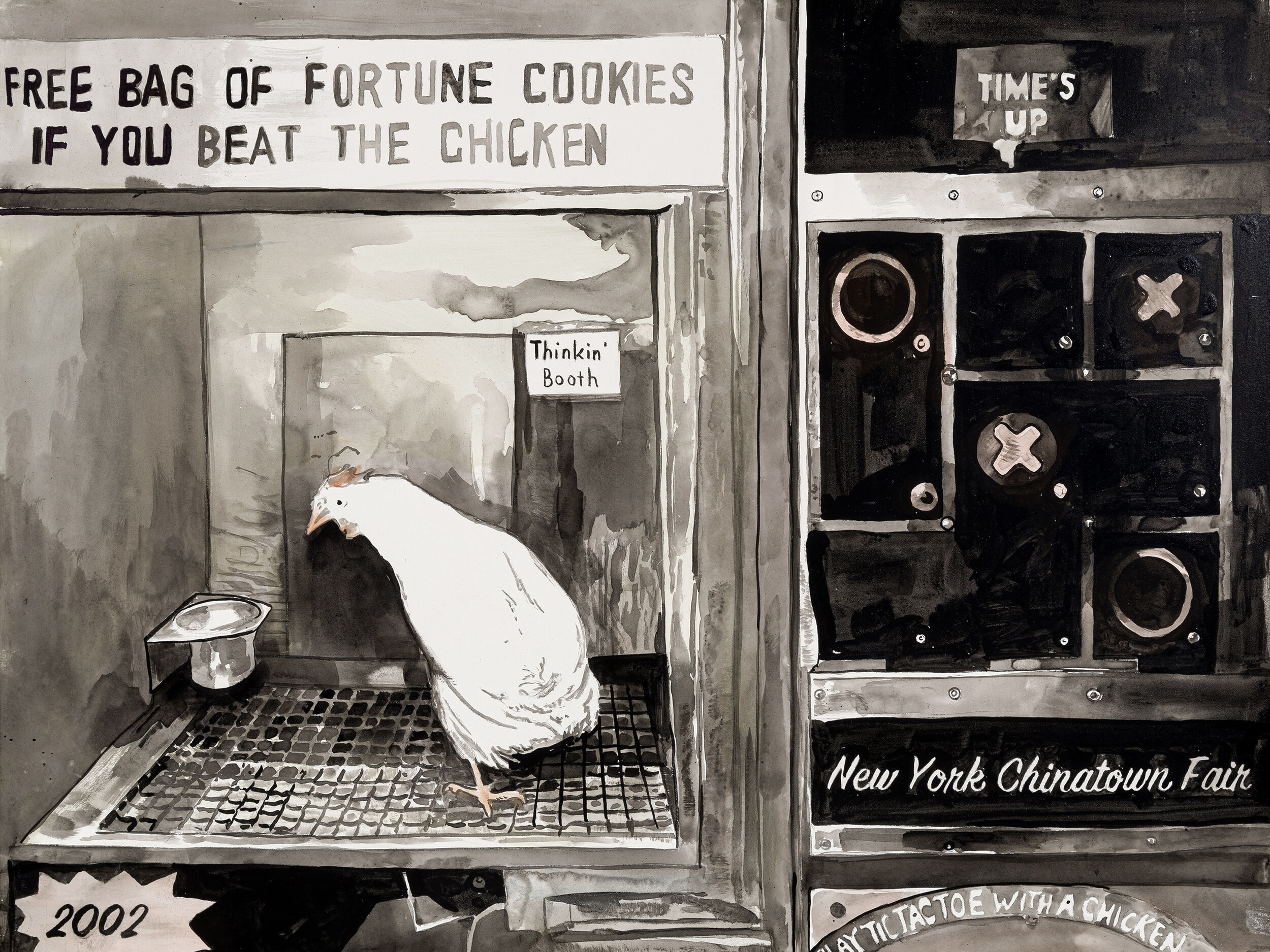

You're at the county fair, the air smells like deep-fried everything, and then you see it. A literal chicken inside a glass booth. It’s sitting there, looking slightly bored, waiting for you to drop a couple of bucks so it can beat you at a game of tic tac toe. It sounds ridiculous because it is. But then you play. And you lose.

Chicken tic tac toe isn't just a weird piece of Americana; it’s a masterclass in behavioral psychology and simple programming masked by feathers and birdseed. Most people think there's some secret "genius" bird behind the glass. Honestly, the bird is just hungry.

How does a creature with a brain the size of a bean outsmart a human being with a college degree? It's not because the chicken has a high IQ. It’s because the game is rigged by logic, not by the bird’s tactical brilliance.

The Science of Operant Conditioning

To understand why this works, you have to look back at the work of B.F. Skinner. He was the father of operant conditioning. Back in the mid-20th century, Skinner and his students—specifically Keller and Marian Breland—realized they could train animals to do almost anything if they broke the actions down into tiny, rewarded steps. This wasn't just about teaching a dog to sit. They were training pigeons to guide missiles and, eventually, chickens to play games.

The Brelands started a company called Animal Behavior Enterprises (ABE). They were the ones who truly commercialized the chicken tic tac toe machine. They knew that if a chicken pecked a specific spot and received a piece of grain, it would repeat that behavior until the end of time.

The bird isn't looking at your "X" and thinking about its "O." It’s waiting for a light to flash.

Inside those booths, there is a hidden console. When it’s the chicken's turn, a small light (invisible or barely noticeable to the player) illuminates a specific spot on the chicken's side of the board. The chicken pecks the light. A hopper releases a single kernel of corn. The chicken is happy. You, however, are frustrated because a farm animal just blocked your winning move.

Why You Can't Actually Win

Here is the kicker: even if the chicken was just pecking at random, you’d still probably struggle to win.

Tic tac toe is what mathematicians call a zero-sum game of "perfect information." This means if both players play perfectly, the game always ends in a draw. There are exactly 255,168 possible games, which sounds like a lot, but in computing terms, it’s nothing. The computer chip inside the chicken's booth is programmed with an unbeatable algorithm.

The computer makes the move. Then, it lights up the corresponding button for the chicken to peck. The chicken is essentially just the "click" on a mouse.

You aren't playing against a bird. You're playing against a hardcoded script that has been solved since the 1950s.

The Casino Mentality of the Fairground

Why do people keep playing? It’s the spectacle. There’s a certain "I can’t believe this" factor that draws a crowd. When a crowd forms, the pressure is on. You’re more likely to make a "blunder"—a technical term for a move that gives away a win—when people are watching you lose to a hen named Henrietta.

Psychologically, humans tend to anthropomorphize the bird. We see intent where there is only instinct. We think the chicken is "thinking." It’s not. It’s just waiting for the grain. This disconnect between what we see and what is actually happening is what makes chicken tic tac toe a staple of roadside attractions like Buckhorn Exchange in Denver or the various "Casino Chickens" that used to haunt the Las Vegas Strip.

The Life of a "Professional" Gamer Bird

A common concern involves the welfare of the birds. Are they stressed? Are they bored?

Most experts in animal behavior note that chickens are surprisingly social and active. In these machines, the "work" they do is essentially a foraging substitute. They peck, they eat. Most modern iterations of these machines (yes, they still exist) have strict regulations on how long a bird can be "on shift." Usually, they work for a few hours with access to water and then go back to a coop.

In fact, some trainers argue that the mental stimulation—even if it's just reacting to lights—is better than sitting in a cramped cage with nothing to do. It’s a job. A weird, corn-funded job.

How to Not Lose Your Dignity

If you find yourself standing in front of a chicken tic tac toe machine, you need to understand the goal. You cannot win. The computer won't let you. The best you can hope for is a draw.

To get a draw against the chicken, you have to follow the standard tic tac toe "draw script":

- Take the center: If the chicken doesn't take it first, you must.

- Corners are key: If you don't have the center, you need the corners to prevent a fork.

- Watch the "L" shapes: This is where most casual players fail. They allow the opponent to create two ways to win simultaneously.

If you play perfectly, you will tie the chicken. The machine will usually display a message like "TIE GAME - THE CHICKEN IS TOUGH!" and you’ll walk away with your pride intact, but without the $5 "I beat the chicken" T-shirt.

✨ Don't miss: Every Icon Skin in Fortnite: What Most People Get Wrong

The Cultural Impact of the Gaming Bird

It’s easy to dismiss this as low-brow entertainment, but it has seeped into pop culture in ways you might not realize. The chicken tic tac toe machine has appeared in movies, documentaries, and even inspired segments on The Late Show with David Letterman.

It represents a specific era of American ingenuity where we used high-level psychological theories to make a buck at a carnival. It’s the intersection of the Cold War-era obsession with "brainwashing" (conditioning) and the classic American hustle.

Today, you can find digital versions or "retro" machines at spots like the Pinball Hall of Fame. People still line up. Even in an age of 4K gaming and VR, there's something infinitely more compelling about a live animal participating in a human game.

What We Get Wrong About the "Smart" Chicken

The biggest misconception is that the chicken is being "taught" the rules of the game. It isn't. You could replace the tic tac toe board with a nuclear launch sequence, and as long as the chicken pecks the blinking light to get its corn, it would "play" that too.

The intelligence isn't in the bird; it's in the interface. The Brelands were geniuses because they realized the animal doesn't need to understand the "why"—it only needs to understand the "when."

💡 You might also like: Ashura the Hedgehog: What Really Happened with the Glitch Known as Sonic the Green Hedgehog

Moving Toward a Draw

Next time you see a chicken tic tac toe setup, don't go in expecting to win a prize. Go in to watch a living relic of behavioral science. Watch the way the bird's head moves—it’s scanning for that light. Notice the timing of the grain dispenser.

If you want to actually test your skills, you're better off playing a human. Humans make mistakes. Humans get distracted. Humans don't have a microchip in their brain telling them exactly where to move to ensure a stalemate.

Actionable Insights for Your Next Fair Visit:

- Acknowledge the script: Accept that the machine is programmed for a draw or a win. You are playing a computer, not a bird.

- Focus on the draw: Use a "center-first" strategy. If the chicken (computer) takes the center, you must take a corner.

- Observe the conditioning: Look for the light cues. It’s a great way to see B.F. Skinner’s theories in real-time action.

- Check the bird: If you're at a smaller, less-regulated fair, ensure the bird has access to water and looks healthy. Most reputable vendors take great care of their "athletes," but it's always good to be an informed consumer.

- Don't bet the house: It’s a novelty. Treat it as a $2 lesson in psychology, not a competitive e-sport.