You’ve probably seen the famous double helix. It’s everywhere. T-shirts, tattoos, movie intros—it’s the universal logo for "science." But honestly, most people treat DNA and RNA like magic spells rather than physical objects. If you actually look at the chemical structure of nucleic acids, you realize they aren't just abstract codes. They are physical, clunky, fascinatingly complex molecules that behave more like high-tech construction equipment than a simple library.

Life is messy.

When we talk about the chemical structure of nucleic acids, we are talking about two main players: Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and Ribonucleic acid (RNA). They share a blueprint, sure. But their differences are what make life possible. If DNA is the master hard drive kept in a climate-controlled room, RNA is the cheap, disposable USB stick you carry in your pocket that eventually loses its cap.

The basic anatomy of a nucleotide

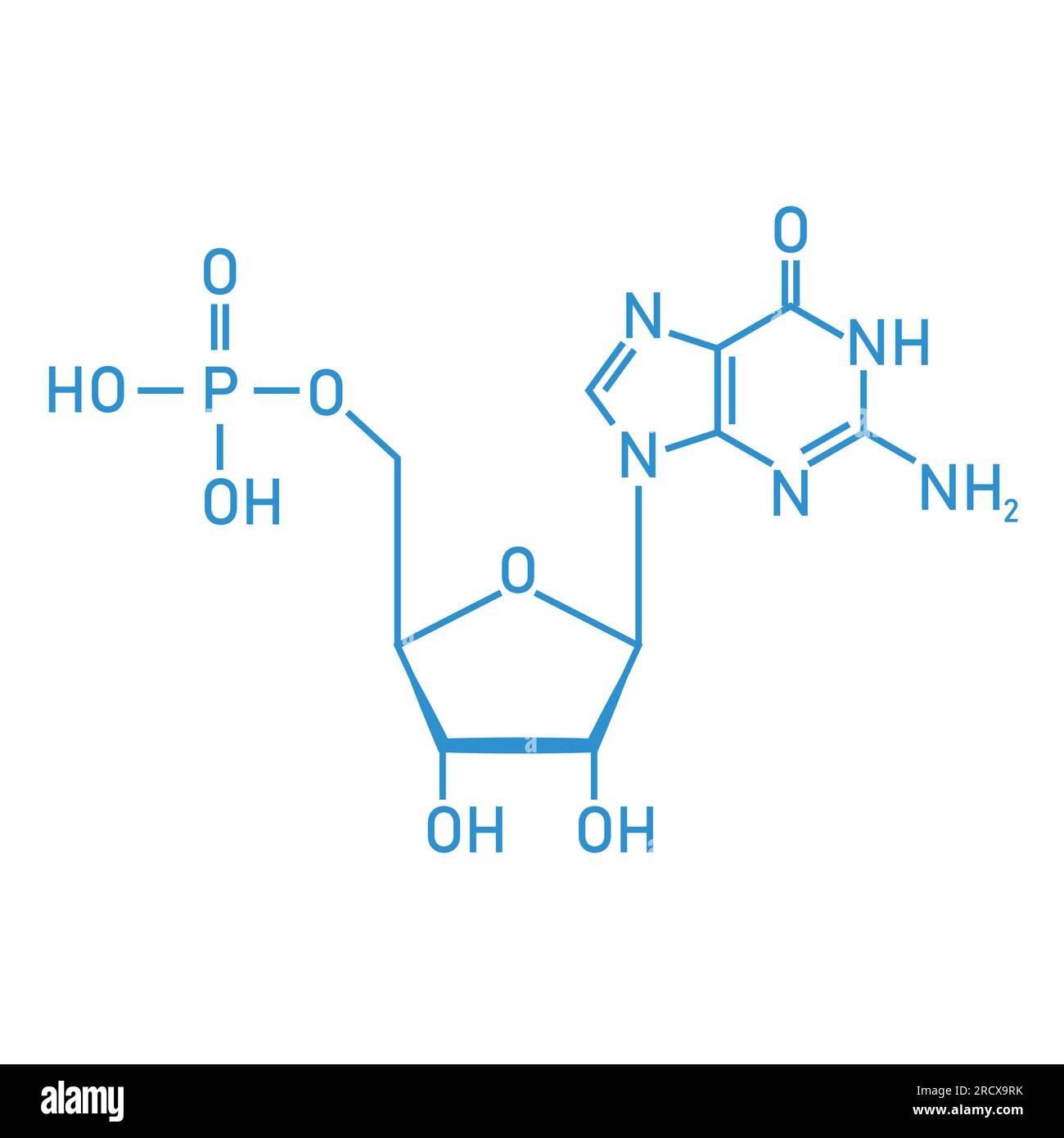

Every nucleic acid is a polymer. That’s just a fancy way of saying it’s a long chain of repeating units called nucleotides. Think of a nucleotide as a three-part kit. You’ve got a phosphate group, a five-carbon sugar, and a nitrogenous base. That’s it. That’s the whole ballgame.

The sugar is the anchor. In DNA, it’s deoxyribose. In RNA, it’s ribose. The only difference is one single oxygen atom. Seriously. DNA is missing an oxygen on the second carbon (hence "deoxy"). It seems like a tiny detail, but that missing oxygen makes DNA way more stable. RNA’s extra oxygen makes it chemically reactive and prone to falling apart. This is why forensic scientists can pull DNA from a 50,000-year-old woolly mammoth, but you can’t easily find RNA from last week’s lunch.

Nitrogenous Bases: The Alphabet of Life

The "bases" are where the information lives. They fall into two camps: Purines and Pyrimidines.

✨ Don't miss: High Protein in a Blood Test: What Most People Get Wrong

Purines are the big guys. Adenine (A) and Guanine (G). They have a double-ring structure. If you’re trying to remember them, just think "Pure As Gold." Pyrimidines—Cytosine (C), Thymine (T), and Uracil (U)—are smaller, single-ring structures.

- DNA uses A, G, C, and T.

- RNA swaps Thymine for Uracil.

Why the swap? It’s a quality control thing. Cytosine can sometimes decay into Uracil naturally. If DNA used Uracil, the cell wouldn't know if the Uracil was supposed to be there or if it was just a damaged Cytosine. By using Thymine, DNA has a built-in error correction system. It’s brilliant engineering by evolution.

Phosphodiester bonds and the sugar-phosphate backbone

The "sides" of the ladder are held together by phosphodiester bonds. This is a covalent bond between the 3' (three-prime) carbon of one sugar and the 5' (five-prime) carbon of the next. This gives nucleic acids directionality.

It’s like a one-way street.

Biologists are obsessed with 5' to 3' direction. Enzymes that read DNA, like DNA polymerase, can only move in one direction. If they try to go the other way, nothing happens. This directional nature of the chemical structure of nucleic acids is why DNA replication is such a headache for the cell, involving "leading" and "lagging" strands.

🔗 Read more: How to take out IUD: What your doctor might not tell you about the process

The Double Helix: More than just a pretty shape

In 1953, James Watson and Francis Crick (relying heavily on Rosalind Franklin’s X-ray diffraction data, which honestly doesn't get enough credit) figured out the double helix. The two strands run "anti-parallel." One goes 5' to 3', the other goes 3' to 5'.

They are held together by hydrogen bonds between the bases.

A pairs with T (two bonds).

G pairs with C (three bonds).

Because G-C pairs have three bonds, they are harder to pull apart. Areas of your genome with lots of Gs and Cs are like "molecular glue." Scientists actually measure the "melting temperature" of DNA—the heat required to unzip the strands—and it's directly tied to how many G-C pairs are in the sequence.

RNA is the weird cousin

While DNA stays in its tidy double helix, RNA is a wild card. Usually, it's single-stranded. But because it's single-stranded, it likes to fold back on itself. It forms loops, hairpins, and complex 3D shapes.

This is why RNA can act like an enzyme (ribozymes). DNA just sits there. RNA actually does things. Messenger RNA (mRNA) carries instructions, but Transfer RNA (tRNA) and Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) are the physical machinery that builds proteins.

💡 You might also like: How Much Sugar Are in Apples: What Most People Get Wrong

Why should you care about this structure?

It isn't just for textbooks. The chemical structure of nucleic acids is the foundation of modern medicine.

- CRISPR Gene Editing: This tech uses a piece of RNA to "guide" a protein to a specific DNA sequence. It works because the RNA base-pairs perfectly with the target DNA.

- mRNA Vaccines: The COVID-19 vaccines used synthetic mRNA. Because we understand the chemical structure—specifically how to modify the bases so the immune system doesn't destroy the RNA immediately—we could turn our cells into temporary vaccine factories.

- Chemotherapy: Many cancer drugs are "nucleoside analogs." They look like real nucleotides but have a slight chemical tweak. When cancer cells try to use them to build new DNA, the "fake" nucleotide jams the machinery and kills the cell.

How to use this knowledge

If you're looking to apply this understanding of the chemical structure of nucleic acids to your life or studies, start with the basics of molecular biology. Understanding the "Central Dogma"—DNA makes RNA makes Protein—is much easier when you visualize the physical molecules.

- Support your DNA repair: While you can't "change" your sequence, you can support the enzymes that maintain it. Micronutrients like folate and B12 are essential for synthesizing new nucleotides.

- Understand your labs: If you ever get a genetic test (like 23andMe), you're looking at SNPs (Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms). That's just a fancy way of saying one "letter" in your chemical structure is different from the "standard" version.

- Keep up with mRNA tech: This isn't just for vaccines anymore. Research is exploding into using mRNA to treat heart disease and rare genetic disorders by "teaching" the body to make missing proteins.

The complexity of these molecules is staggering. We are essentially walking, talking chemical reactions powered by the most sophisticated data storage system in the known universe. By looking at the atoms—the oxygens, the nitrogens, the phosphates—we move past the "magic" and start to see the actual mechanics of being alive.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge:

- Study the "Chargaff’s Rules": Look up Erwin Chargaff’s work to see how the 1:1 ratio of A-T and G-C was discovered before we even had a picture of DNA.

- Explore Epigenetics: Learn how "methyl groups" (just a carbon and three hydrogens) can attach to the DNA backbone to turn genes on or off without changing the sequence itself.

- Look into Ribozymes: Investigate how RNA molecules can act as catalysts, which supports the "RNA World" hypothesis—the idea that RNA, not DNA, was the original spark of life.