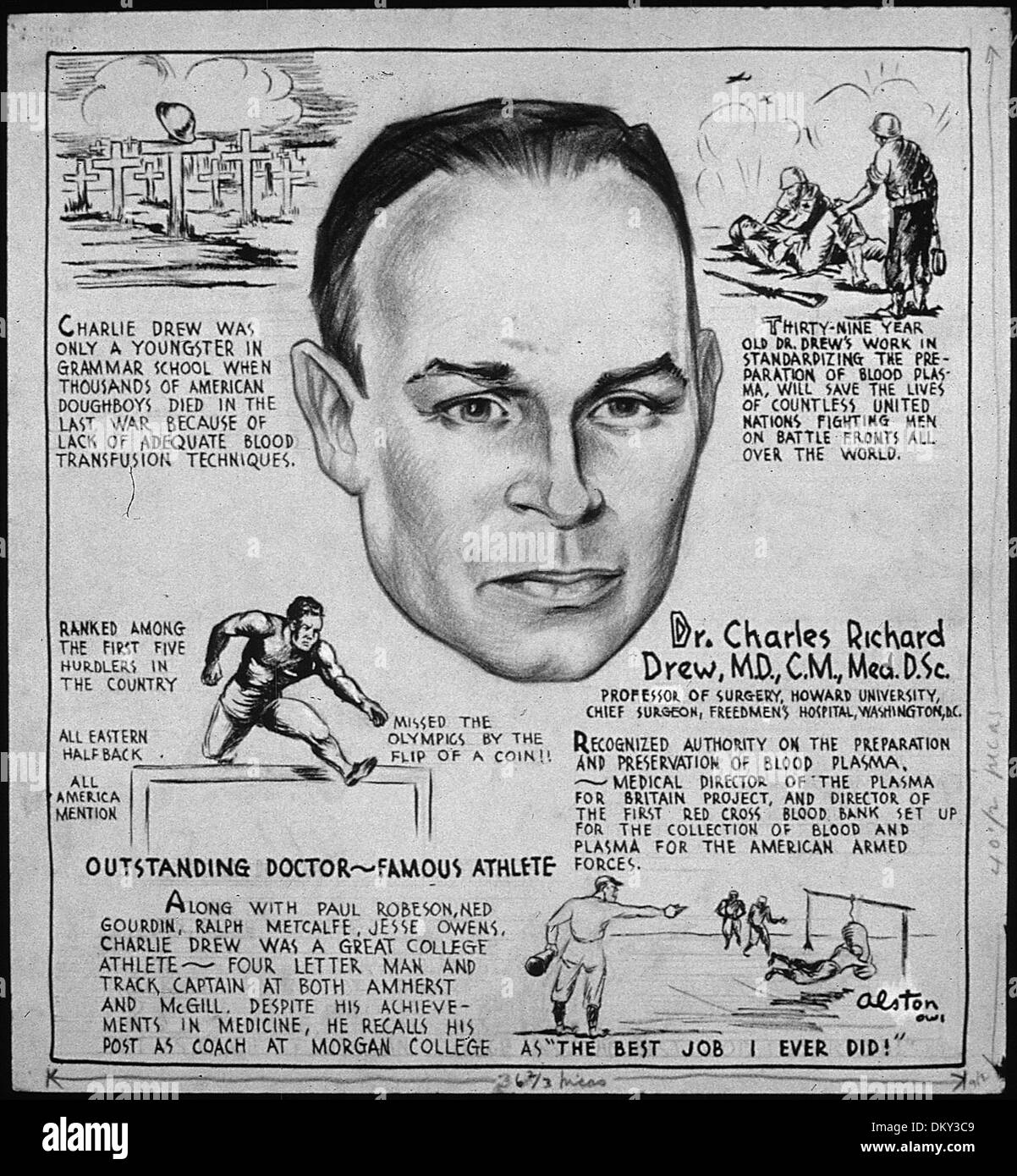

If you’ve ever seen a "bloodmobile" parked outside a local library or office building, you’re looking at a ghost of 1940s innovation. Most people know Dr. Charles Richard Drew as the man who "invented" blood banks. That’s a bit of a simplification, honestly. People were messing around with blood transfusions long before he arrived on the scene. But Drew? He was the one who figured out how to make it work at a scale that could actually save a literal army.

He’s a legend. But he’s also a man whose real story is often buried under a very famous, very persistent myth about how he died.

The Breakthrough: Why Plasma Was the Secret Sauce

Before the 1940s, if you needed blood, you basically needed a donor in the next room. Whole blood is finicky. It spoils fast. Even refrigerated, you only had a few days before it became useless.

Charles Richard Drew realized the problem wasn't the blood itself—it was the cells.

While working on his doctorate at Columbia University—where he became the first African American to earn a Doctor of Medical Science degree—he obsessed over plasma. Plasma is the liquid part of blood. It doesn't have the red cells that carry oxygen, but it does have the proteins and clotting factors needed to treat shock.

The big win? * Plasma can be kept for much longer than whole blood.

- It can be dried into a powder.

- It can be given to anyone, regardless of their blood type.

Basically, Drew turned a perishable medical product into a shelf-stable commodity. This wasn't just "science"; it was logistics. When World War II kicked off, the "Blood for Britain" project needed exactly that kind of logistics. Drew was the guy who standardized the whole thing: the sterile needles, the refrigerated trucks, the testing for bacteria. He shipped over 5,000 liters of plasma across the Atlantic while London was being bombed.

👉 See also: Nuts Are Keto Friendly (Usually), But These 3 Mistakes Will Kick You Out Of Ketosis

The Red Cross Resignation: A Matter of Science (and Dignity)

You’d think a guy who just saved thousands of Allied soldiers would be treated like a hero without any "buts."

Not in 1941.

After his success with Britain, the American Red Cross tapped Drew to lead a new national blood program. But then the U.S. War Department dropped a bombshell: they ordered that blood from Black donors be segregated from blood from white donors. At first, they didn't even want Black donors at all.

It was a slap in the face.

Drew didn't just get angry; he used his expertise to point out how stupid the policy was. He famously argued that there is absolutely no scientific difference between the blood of different races. "It is fundamentally wrong for any great nation to willfully discriminate against such a large group of its people," he later said.

He resigned in 1942. He couldn't lead a system that ignored the very science he had perfected. He went back to Howard University to do what he felt was his "real" work: training the next generation of Black surgeons so they could break the same barriers he had spent his life smashing.

✨ Don't miss: That Time a Doctor With Measles Treating Kids Sparked a Massive Health Crisis

The Car Accident: Debunking the Hospital Myth

If you’ve heard about Charles Richard Drew, you’ve probably heard the tragic story of his death. The story goes like this: Drew was in a car accident in rural North Carolina, he was rushed to a white-only hospital, and he died because they refused to give him a blood transfusion.

It’s a powerful, poetic sort of tragedy. It feels like the kind of cosmic irony history loves.

But it’s not true.

On April 1, 1950, Drew was driving to a medical conference at the Tuskegee Institute. He was exhausted. He’d performed surgeries all day before hitting the road. He dozed off, the car flipped, and he suffered massive internal injuries.

He was taken to Alamance General Hospital. Despite being a segregated hospital in the Jim Crow South, the white doctors on duty actually recognized him. They knew who he was. They worked on him for over an hour. They even gave him a transfusion of the very plasma he helped pioneer.

His injuries were just too severe. His brain was damaged, and his chest was crushed.

🔗 Read more: Dr. Sharon Vila Wright: What You Should Know About the Houston OB-GYN

The myth started because, at the time, Black people were frequently turned away from hospitals. It was a common horror. People assumed that’s what happened to Drew because it happened to so many others. But according to the doctors who were in the car with him—John Ford and Walter Johnson—the hospital did everything they could.

Why He Still Matters (Beyond the Science)

Drew wasn't just a "blood guy." He was an athlete first—a star at Amherst College—and he brought that competitive, team-oriented energy to medicine. He was obsessed with excellence because he knew that for a Black doctor in the 1940s, "average" wasn't an option.

His real legacy isn't just the bloodmobile or the plasma powder. It’s the surgeons he trained at Howard. He knew that one man could only do so much, but a whole generation of elite surgeons could change the face of American healthcare.

Actionable Insights from Drew’s Career

If we look at how Drew operated, there are a few things anyone can take away:

- Systematize the Chaos: Drew didn't just "discover" plasma storage; he created the process for it. He standardized the bottles, the temperatures, and the transport. Success usually lies in the workflow, not just the idea.

- Stick to the Data: When the Red Cross tried to segregate blood, Drew didn't just argue from a place of emotion—though he had every right to. He argued from a place of biological fact. It’s much harder to ignore an expert who has the data on their side.

- Invest in Others: Drew left the "fame" of the National Blood Bank to go back to teaching. He knew his "greatest and most lasting" contribution would be the people he mentored.

If you want to honor his legacy today, don't just remember the "blood bank" factoid. Support programs that bridge the gap for minority students in STEM. Or, more simply: go give blood. The system that allows you to do that in twenty minutes at a local van exists because a guy in 1940 decided that "it can't be stored" wasn't a good enough answer.

To truly understand the depth of his impact, look into the history of Freedmen’s Hospital (now Howard University Hospital). It was the epicenter where Drew proved that medical excellence knows no racial boundary. You can also visit the Charles Richard Drew Memorial Bridge in Washington, D.C., or read his original 1940 dissertation, Banked Blood, which remains a foundational text in transfusion medicine.