Honestly, if you’ve ever seen a bloodmobile parked outside a local library or donated a pint at a Red Cross drive, you’re looking at the living legacy of Charles Richard Drew. He basically invented the playbook for how we move life-saving fluid from one person’s arm to another’s across hundreds of miles. But the story most people know—the one about the "Father of Blood Banking"—is often buried under half-truths and one massive, persistent myth about how he died.

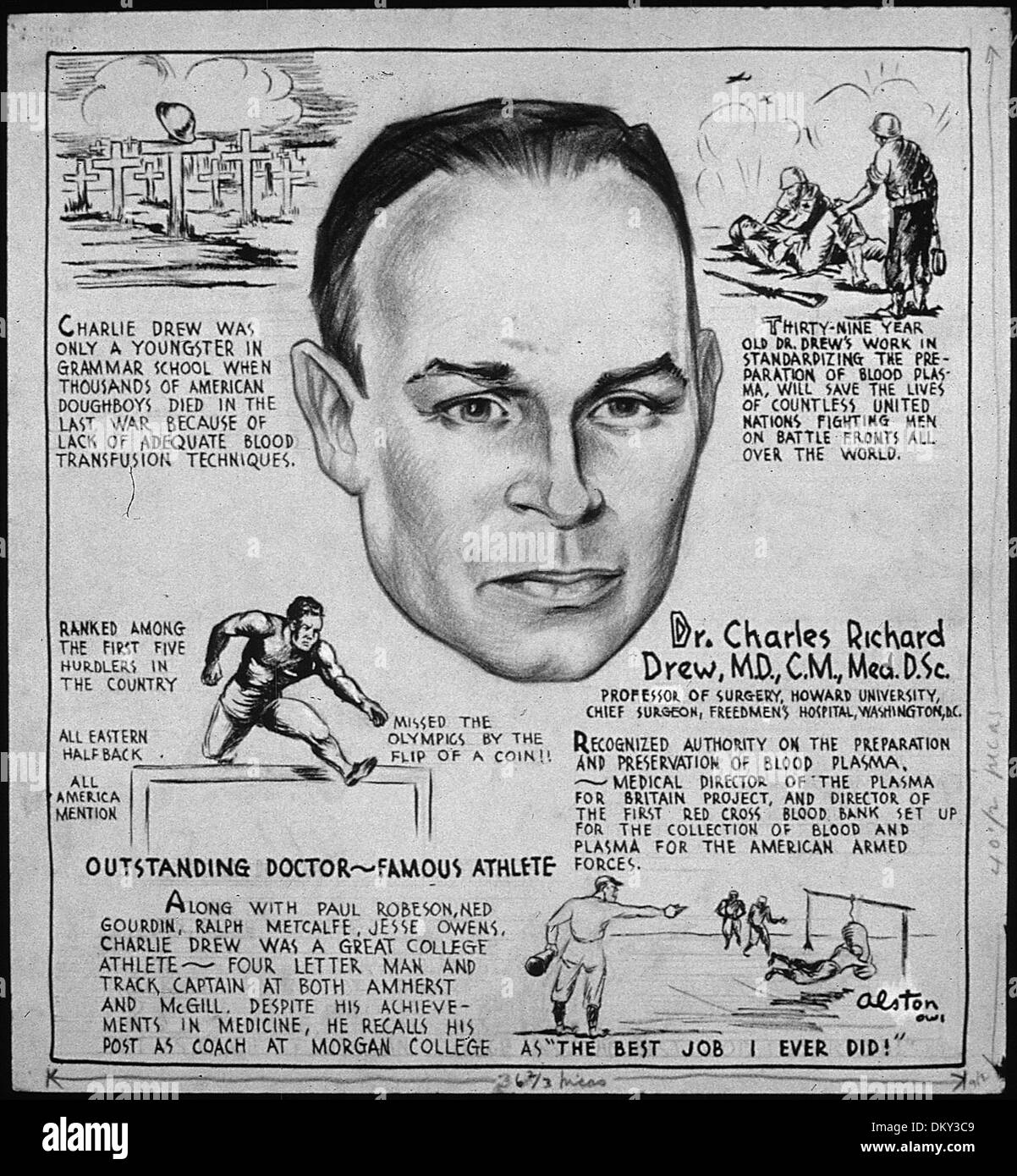

He wasn't just a guy in a lab coat. He was an All-American athlete who could outrun almost anyone on a track. He was a surgeon who fought a system that told him his own blood wasn't "pure" enough to be mixed with others. Most importantly, he was a scientist who realized that if you want to save a soldier bleeding out on a battlefield in 1940, you don't send whole blood. You send plasma.

The Plasma Breakthrough: Why Charles Richard Drew Changed Everything

Before the late 1930s, blood transfusions were a logistical nightmare. Whole blood has a shelf life of maybe a week before it starts to go bad. You couldn't exactly ship it across the Atlantic to a war zone.

While working on his doctorate at Columbia University—becoming the first African American to earn a Doctor of Medical Science there—Drew focused on a simple but radical idea. Blood plasma (the liquid part of blood without the red cells) is way more stable than whole blood.

- Shelf life: Plasma could be stored for months, not days.

- Universal use: Unlike whole blood, which requires matching types (A, B, AB, O), plasma can be given to anyone in an emergency.

- Dehydration: He figured out you could even dry plasma into a powder and reconstitute it later.

This wasn't just a "neat discovery." It was the difference between life and death for thousands of Allied soldiers during the "Blood for Britain" project. Drew organized the whole thing. He standardized how blood was collected, tested for bacteria, and processed. He basically created the first large-scale industrial blood bank from scratch.

Resigning in Protest: The Red Cross Controversy

You'd think a man who saved the British army would be treated like a hero at home. Kinda. In 1941, the American Red Cross appointed him as the first medical director of their new national blood bank program.

📖 Related: Dr. Sharon Vila Wright: What You Should Know About the Houston OB-GYN

Then things got ugly.

The U.S. military ordered the Red Cross to exclude Black donors entirely. Later, they "softened" the policy to allow Black donors but insisted the blood be segregated by race.

Dr. Drew didn't just disagree; he was livid. He knew better than anyone that there is zero scientific difference between the blood of a Black person and a white person. Race is a social construct; biology doesn't care.

"It is fundamentally wrong for any great nation to willfully discriminate against such a large group of its people... They need the blood." — Charles Richard Drew

He didn't stick around to oversee a system built on bad science and bigoted logic. He resigned. He went back to Howard University to do what he felt was even more important: training the next generation of elite Black surgeons. He wanted to make sure that even if the system was broken, the doctors coming out of it were undeniable.

👉 See also: Why Meditation for Emotional Numbness is Harder (and Better) Than You Think

What Really Happened: Debunking the Death Myth

If you've heard the story that Charles Richard Drew bled to death because a "whites-only" hospital refused to treat him, you’ve heard a myth.

It’s a story that feels true because, in 1950, that did happen to many Black Americans. It’s a powerful, tragic irony—the man who invented the blood bank dying because he couldn't get blood. Even the show MASH* repeated it in an episode.

But it’s not what happened.

On April 1, 1950, Drew was driving to a medical conference at Tuskegee Institute. He fell asleep at the wheel in North Carolina. The car flipped. His injuries were catastrophic—his leg was nearly severed, and his chest was crushed.

When he was taken to Alamance General Hospital, the white doctors on duty actually knew who he was. They worked desperately to save him. They gave him transfusions. They consulted with his companions. But the damage was too far gone. His family even wrote letters later thanking the hospital staff for the care they provided.

✨ Don't miss: Images of Grief and Loss: Why We Look When It Hurts

The myth likely persists because a young Black veteran named Maltheus Avery died under those exact circumstances (denied care at a white hospital) just months later in the same area. Over time, the stories merged in the public consciousness.

The Modern Impact of Drew’s Work

We still use the "bloodmobile" concept he pioneered. He was the one who realized you had to go to the donors, not wait for them to come to you.

Why his legacy matters in 2026:

- Emergency Medicine: His work on treating "shock" with fluid replacement is the bedrock of every ER in the world.

- Standardization: Every time a blood bag is scanned and tracked, that's the evolution of the "Blood for Britain" logistics.

- Education: As a professor at Howard, he didn't just teach; he fought for Black doctors to be admitted to the American Medical Association (AMA) and other specialty boards.

Actionable Insights for Today

If you want to honor Dr. Drew's legacy beyond just reading a history article, there are real things you can do that directly relate to his life's work.

- Check Blood Supply Realities: Don't just donate when there's a disaster. Blood banks need a "constant" flow because red cells still only last about 42 days.

- Support Health Equity: Dr. Drew’s biggest frustration was the "unscientific" barriers in medicine. Support organizations like the National Medical Association (NMA), which was founded because Black doctors were originally excluded from the AMA.

- Encourage Diversity in STEM: Drew believed that "excellence of performance will transcend artificial barriers." Mentoring students from underrepresented backgrounds in medicine is the most "Dr. Drew" thing you can do.

Charles Richard Drew was a man who lived at the intersection of brilliant science and a deeply flawed society. He chose to lead with the science and fight the flaws. Every time a life is saved by a transfusion today, his work is the silent engine behind it.