Charles Reade was a bit of a madman. Honestly, if you walked into his home in the mid-1800s, you wouldn't find a peaceful study with a quill and a nice view of a garden. Instead, you'd likely trip over massive stacks of oversized scrapbooks—huge, towering things filled with newspaper clippings, police reports, and medical journals. He called them his "indices." This wasn't a hobby. It was an obsession. For the The Cloister and the Hearth author, fiction wasn't just about telling a story; it was about proving a point with the cold, hard weight of facts.

He didn't care about being "literary." He cared about being right.

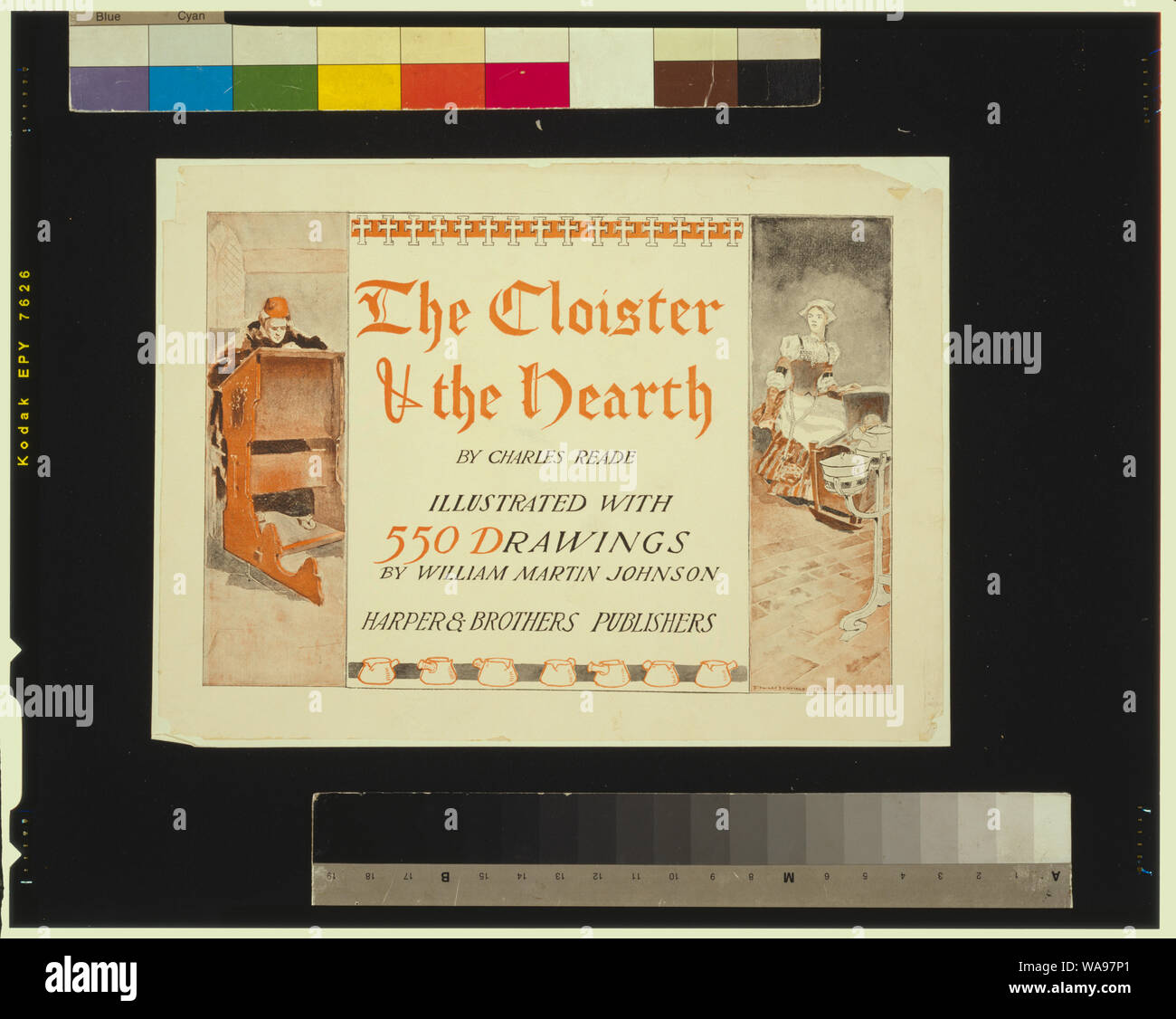

Most people today know Reade, if they know him at all, for The Cloister and the Hearth. It’s often called one of the greatest historical novels ever written, but the man behind it was a bundle of contradictions. He was a fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford, yet he spent his time fighting for the rights of prisoners and mental health patients. He was a lawyer who never really practiced law but used his legal mind to tear down the Victorian establishment. He was a playwright who wanted to be Shakespeare but ended up being the king of the "sensation novel."

Why Charles Reade Wrote Like a Private Investigator

When you sit down to read Reade, you notice something weird immediately. He doesn't sound like Dickens or George Eliot. There’s a frantic, almost cinematic energy to his prose. That’s because he didn't just sit and dream. He researched.

Take The Cloister and the Hearth. It’s set in the 15th century and follows the parents of the Great Erasmus, but Reade treated it like a contemporary investigation. He spent years digging through old chronicles. He wanted to know exactly what a roadside inn in 1470 smelled like. He wanted to know the specific weight of a crossbow. This "Matter-of-Fact Romance," as he called it, was his attempt to bridge the gap between dry history and visceral human emotion.

He had this theory that truth was stranger than fiction. It sounds like a cliché now, but Reade lived it. He once wrote, "I have no secrets of my own. I only tell what I have seen, or what I have read in the records of the world."

It worked.

But it also made him a lot of enemies. Critics hated him. They called his work "industrial" and "sensational." They weren't entirely wrong. Reade loved a good cliffhanger. He loved a villain you could hiss at. But underneath the melodrama was a radical empathy that most of his peers lacked. He wasn't just entertaining the middle class; he was trying to wake them up.

🔗 Read more: Curtain Bangs on Fine Hair: Why Yours Probably Look Flat and How to Fix It

The Scandalous Success of The Cloister and the Hearth

Originally, the book wasn't even a book. It started as a shorter serial titled A Good Fight in the magazine Once a Week. But Reade had a massive falling out with the publishers. He was notoriously prickly about his "artistic integrity" (which usually meant he wanted more money or more control). He pulled the story, expanded it massively, and turned it into the four-volume epic we know today.

It's a long read. It's dense. But it’s surprisingly modern in its pacing. You’ve got Gerard, the young artist, trekking across Europe, dodging bandits, dealing with corrupt monks, and falling in love with Margaret. It’s a road movie in parchment and ink.

What makes it stick, though, is the central conflict: the battle between the "cloister" (the restrictive, often hypocritical religious life) and the "hearth" (the warmth of domestic love and family). Reade was obsessed with this tension. He lived his own version of it, too. He never married, but he lived for years with an actress named Laura Seymour. It was a "scandalous" arrangement for the time, and it probably informed a lot of the yearning you see in his characters.

Breaking Down Reade’s Greatest Hits

The Cloister and the Hearth is the masterpiece, sure. But Reade was a prolific machine. He didn't just do history.

- Hard Cash: This was basically an exposé of the private asylum system. Reade was furious about how easy it was for greedy relatives to lock "annoying" family members away in madhouses. He used real cases he’d documented in those massive scrapbooks.

- It Is Never Too Late to Mend: This one took on the prison system. It was so brutal and so accurate that it actually led to real-world debates about prison reform. He showed the "crushing" of souls under the silent system. It’s dark stuff.

- Griffith Gaunt: A story of jealousy and bigamy. It caused a huge stir in America and England because it was seen as "immoral." Reade, of course, defended it by saying he was just reporting on human nature.

The Beef with the Critics

Reade didn't take criticism well. At all.

When a critic panned his work, Reade didn't just ignore it. He sued. Or he wrote long, scathing letters to the editor. He once kept a "Black List" of critics he felt had wronged him. He was convinced that there was a conspiracy among the "anonymuncules" (his word for anonymous critics) to keep him down.

There’s a funny story about him getting so angry at a review that he printed a pamphlet just to call the reviewer a liar. He was the 19th-century version of a celebrity who spends all day arguing with trolls on social media.

💡 You might also like: Bates Nut Farm Woods Valley Road Valley Center CA: Why Everyone Still Goes After 100 Years

But here’s the thing: he was often right. He saw that the Victorian literary world was a bit of a "boy's club." He was an outsider who forced his way in through sheer volume and research. He didn't care about flowery metaphors if a plain sentence could do the job of exposing a corrupt jailer.

The Scrapbook Method: Genius or Madness?

Let’s talk about those scrapbooks again because they are the key to understanding him. Reade didn't trust his memory. He didn't even trust his imagination. He trusted the archive.

He would spend hours cutting out snippets from the Times or the Police Gazette. If he was writing about a shipwreck, he made sure he had three different accounts of real shipwrecks to pull from. This gives his writing a "gritty" feel. It’s textured. You can almost feel the grime of the London streets or the cold stone of the monastery.

Some called it "plagiarism." Reade called it "evidence."

What Most People Get Wrong About Reade

A lot of people think of him as just another dusty Victorian novelist. Someone to be assigned in a grad school seminar and then forgotten. That’s a mistake. Reade was a populist. He wanted to be read by everyone—from the scholars at Oxford to the miners in Australia.

He wasn't trying to create "Art" with a capital A. He was trying to create a mirror.

He also wasn't a stuffy moralist. While he cared about reform, he also loved a good explosion, a dramatic rescue, and a tragic misunderstanding. He was a man of the theater. He wrote dozens of plays, and he often structured his novels like stage dramas. You can see it in the dialogue; it’s snappy. It moves.

📖 Related: Why T. Pepin’s Hospitality Centre Still Dominates the Tampa Event Scene

Why You Should Care Today

We live in an age of "true crime" and "investigative journalism." In a way, Charles Reade was the grandfather of that style. He pioneered the idea that fiction could be a weapon for social change based on documented reality.

If you pick up The Cloister and the Hearth, don't look at it as a history lesson. Look at it as a survival story. It’s about two people trying to find a tiny bit of happiness in a world that wants to put them in boxes. Whether that box is a monk’s cell or a social class, the struggle is the same.

Reade’s life was a fight. He fought for his books, he fought for his friends, and he fought for people who couldn't fight for themselves. He was loud, he was arrogant, and he was often exhausting. But he was never boring.

The Real Legacy of Charles Reade

When he died in 1884, he had "Author, Dramatist, and Journalist" put on his tombstone. He wanted to be remembered for the work. And while the scrapbooks are gone and the critics are forgotten, the story of Gerard and Margaret remains.

It remains because Reade understood one fundamental truth: facts provide the skeleton, but empathy provides the heart.

Actionable Steps for Exploring Reade’s World

If you’re looking to dive into the work of this Victorian powerhouse, don't just start anywhere. Here is the best way to tackle his massive bibliography without getting overwhelmed.

- Start with the "Road Movie": Get a copy of The Cloister and the Hearth. Don't try to rush it. Read it for the atmosphere. Pay attention to how Reade describes the different countries Gerard travels through; he’s trying to show you the birth of the modern world.

- Look for the Social Novels: If you like "social justice" themes, move on to It Is Never Too Late to Mend. It’s a tough read because of the prison scenes, but it’s a masterclass in how to use fiction to highlight systemic abuse.

- Visit the Sources: For the truly nerdy, look up the life of Erasmus. Seeing how Reade took the bare bones of a historical figure's parentage and turned it into a 500-page epic is a fascinating lesson in creative adaptation.

- Check Out His Contemporaries: Compare Reade to Wilkie Collins. Both wrote "sensation novels," but where Collins focused on mystery and psychology, Reade focused on the physical world and social institutions. It’s a great way to see the two sides of 19th-century popular fiction.

- Analyze the "Matter-of-Fact" Style: Next time you read a modern thriller that uses real-world news events as a backdrop, think of Reade. He was the one who proved that the "real" could be just as exciting as the "imagined."

Charles Reade didn't want to be a statue in a park. He wanted to be a voice in your head, reminding you that the world is complicated, unfair, and deeply beautiful. He succeeded.