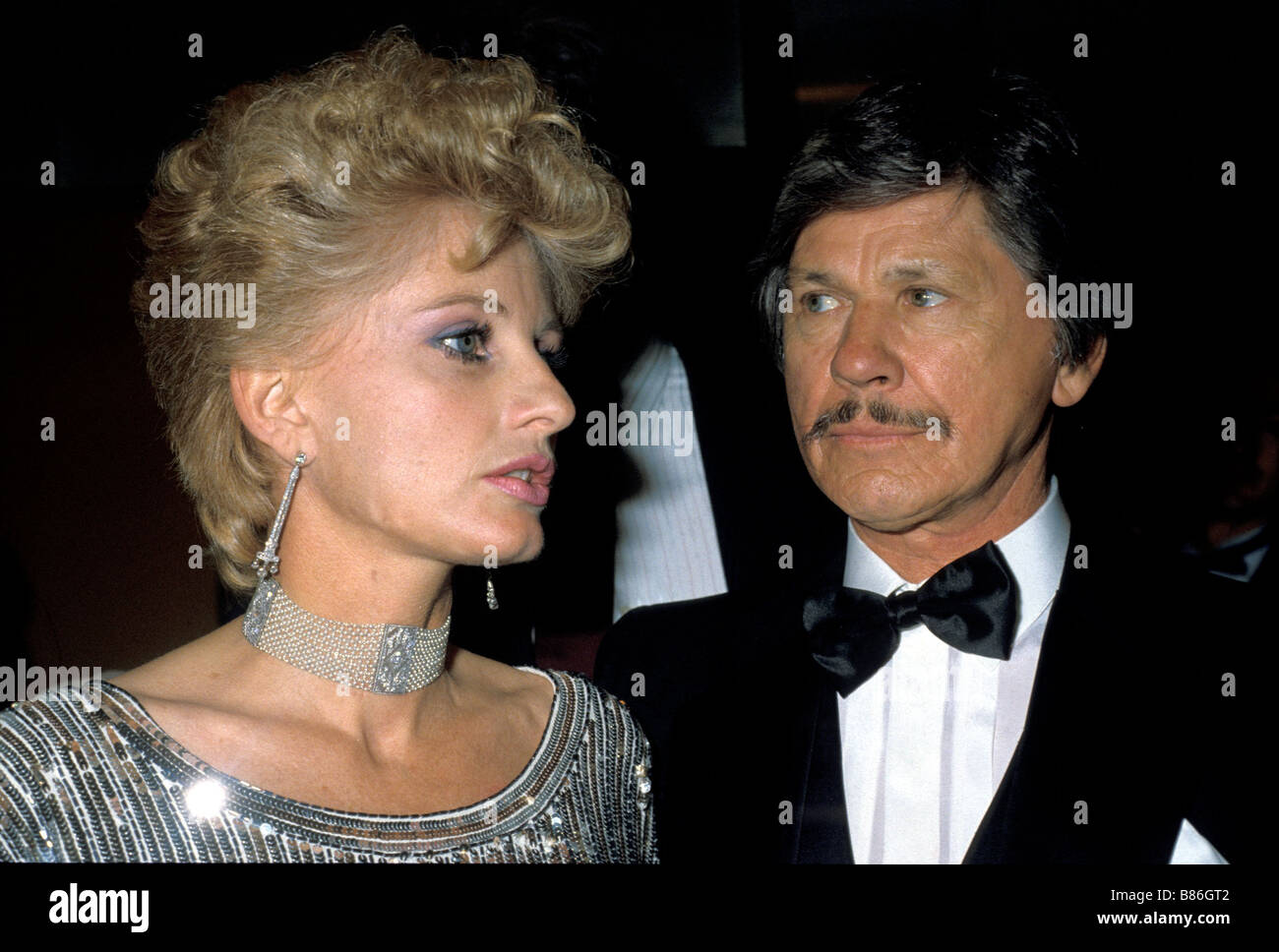

Hollywood loves a scandal. But usually, the scandal burns out after a few tabloid cycles and some messy court dates. With Charles Bronson and Jill Ireland, the drama was just the prologue. Most people remember them as the inseparable duo of 1970s action cinema—the craggy-faced tough guy and the elegant British blonde who seemed to be in every single movie together.

It was more than just a casting gimmick. Honestly, it was a survival tactic.

Their story didn't start with a meet-cute at a gala. It started with a threat. Or a promise, depending on how you view Charles Bronson’s legendary lack of a filter. In 1963, on the set of The Great Escape, Bronson looked at his co-star David McCallum—the heartthrob from The Man from U.N.C.L.E.—and basically told him, "I'm going to marry your wife."

He wasn't joking. He did exactly that.

The Heist of the Century (and the Heart)

You’ve got to understand who Charles Bronson was to get why this worked. He wasn't some smooth-talking Casanova. He was a former coal miner from Pennsylvania, one of 15 kids, a guy who grew up so poor he once had to wear his sister’s dress to school because there were no other clothes. He was hard.

Jill Ireland was different. She was a wine importer's daughter from London, a former dancer with a refined air that shouldn't have fit with Bronson’s "human cliff face" aesthetic.

💡 You might also like: Kellyanne Conway Age: Why Her 59th Year Matters More Than Ever

When they finally married in 1968, the industry expected a train wreck. Instead, they built a fortress. They had this massive, chaotic family—seven kids in total. This included children from their previous marriages, their biological daughter Zuleika, and their adopted daughter Katrina.

They didn't do the "Hollywood" thing where parents vanish to Europe for six months of filming. They moved the whole circus. If Charlie was filming a Western in Spain or a thriller in Italy, the kids, the nannies, and the luggage all went too. It was a traveling commune centered around two people who simply refused to be apart.

Why They Made 16 Movies Together

Critics hated it. They really did. If you look at reviews from the '70s and '80s, journalists were constantly groaning about Jill Ireland being "shoehorned" into Bronson’s projects. From The Valachi Papers to Death Wish II, if Bronson was the lead, Ireland was usually the love interest, the victim, or the mystery woman.

But here’s the thing: Bronson didn't care about the critics. He barely even liked acting. For him, movies were a paycheck to support his family, and he figured if he had to spend twelve hours a day on a set, he might as well spend them with his wife.

- The Power Dynamic: Bronson would often make Ireland’s casting a condition of his contract. No Jill, no Charlie.

- The Chemistry: In From Noon till Three (1976), they actually got to show some range. It’s a weird, satirical Western-comedy that subverts the whole "tough guy" trope. It’s probably the most "them" they ever were on screen.

- The Variety: They played everything from mobsters and their molls to a Secret Service agent and the First Lady in Assassination (1987), which was sadly her final film.

Was she a great actress? She was capable. Was she a great partner? According to everyone who knew them, she was the only person on earth who could truly handle Bronson’s moods. He was notoriously prickly, silent, and suspicious of outsiders. She was his bridge to the world.

📖 Related: Melissa Gilbert and Timothy Busfield: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

The Battle No Action Hero Could Win

The 1980s shifted from glamour to a brutal, public fight for life. In 1984, Jill was diagnosed with breast cancer.

This is where the "tough guy" image of Charles Bronson actually became real. He didn't just play a hero; he became a caregiver. He was devastated, but he stayed. He watched her undergo a radical mastectomy and grueling rounds of chemotherapy.

Ireland, ever the worker, didn't just retreat. She wrote. She became a spokesperson for the American Cancer Society and penned books like Life Wish. She was terrifyingly honest about the loss of her femininity, the fear of death, and the strain it put on her marriage.

Then came the second blow. Their adopted son, Jason McCallum, was spiraling into heroin addiction. Jill spent her remaining energy trying to save him, a struggle she detailed in her second book, Life Lines. She died in May 1990. Jason had died of an overdose just six months earlier.

The Aftermath and a Strange Final Tribute

Bronson was never the same. He eventually remarried, but the light had clearly gone out. When he died in 2003, a strange and touching detail emerged about their bond.

👉 See also: Jeremy Renner Accident Recovery: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

Jill had been cremated, and Charles had kept her ashes in a very specific place: a hollowed-out walking cane. He took it everywhere. When he was finally buried at Brownsville Cemetery in Vermont, that cane—and Jill’s ashes—were buried with him.

It’s easy to look back at their 16 films and see them as kitschy artifacts of a bygone era of machismo. But if you look closer, you see a couple that used the Hollywood machine to stay together against the odds. They weren't perfect, and their beginning was messy, but they ended as one of the few genuine partnerships the industry ever produced.

How to Explore the Bronson-Ireland Legacy

If you're looking to dive deeper into their work beyond the standard Death Wish sequels, start with these specific steps to get a real sense of their dynamic:

- Watch Hard Times (1975): This is arguably Bronson’s best film. Jill’s role is smaller, but the chemistry is quiet and grounded. It shows why they worked.

- Read Life Wish: It’s out of print but easy to find used. It’s a masterclass in celebrity vulnerability and still holds up as a powerful health memoir.

- Find From Noon till Three: It’s the hidden gem of their filmography. It’s funny, cynical, and lets both of them play against type in a way they never did again.

The Bronson-Ireland era wasn't just about movies; it was about two people who decided the world was too cold to face alone. They built their own world instead.