If you’ve ever sat in traffic on Franklin Street during a summer thunderstorm, you know that "sink or swim" vibe isn't just a metaphor. It’s reality. The sky turns a bruised purple, the drains start gurgling backward, and suddenly, the intersection near the Varsity Theatre looks more like a swimming pool than a road. Chapel Hill NC flooding isn't some rare "once in a lifetime" event anymore. It's basically a seasonal tradition at this point, but one that costs local businesses and homeowners millions of dollars.

Chapel Hill is built on a series of ridges and valleys. It’s literally in the name—it’s a hill. But those hills feed directly into a network of creeks that were never meant to handle the sheer volume of concrete we’ve poured over the last fifty years. When the rain hits the asphalt, it doesn't soak in. It sprints. It races down those hills and slams into the lowest points, usually right where people are trying to live or grab a coffee.

The Geography of a Bad Day: Where the Water Actually Goes

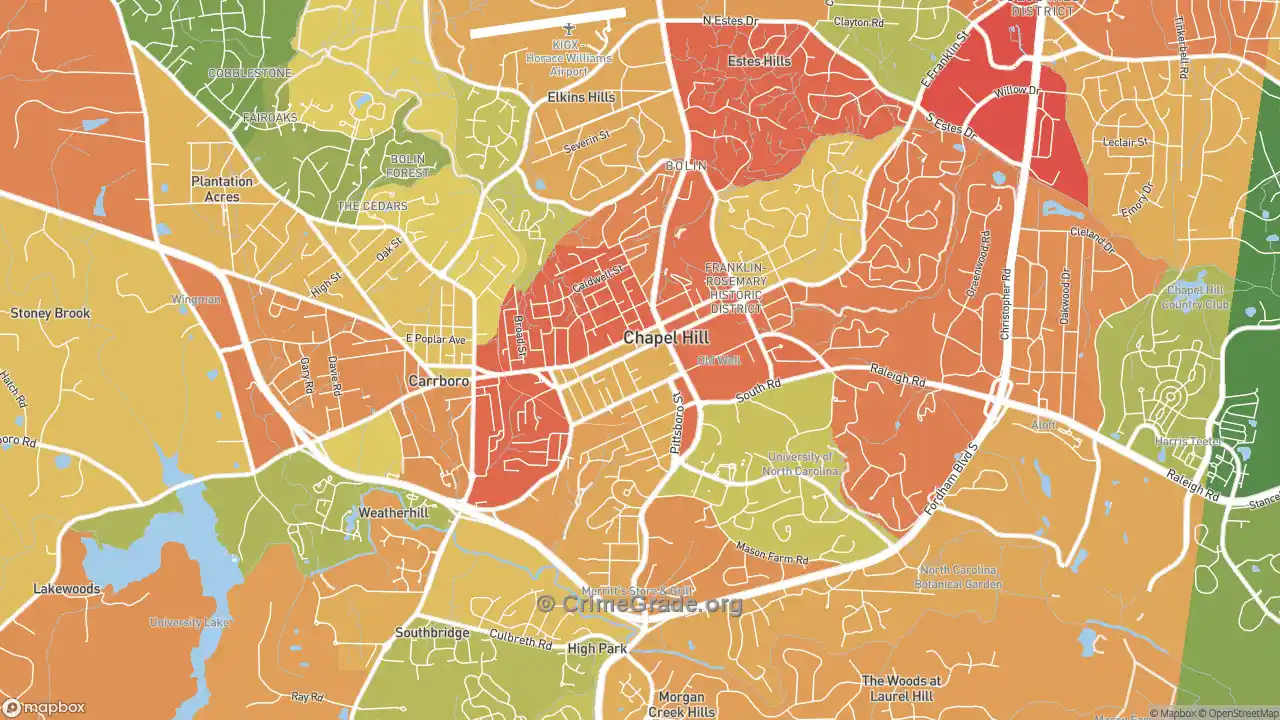

Most people think flooding is just about being near the ocean. Wrong. In a place like the Triangle, it’s all about topography and "impervious surfaces." Basically, that’s a fancy way of saying "stuff water can’t get through."

Take Bolin Creek. It’s beautiful for a Saturday morning hike, but it’s also a massive drainage pipe for the town. When a storm stalls over Orange County, Bolin Creek and Booker Creek act like overwhelmed gutters. You’ve probably seen the photos of Camelot Village. It’s arguably the most famous spot for Chapel Hill NC flooding. Why? Because it sits squarely in the floodplain of Booker Creek. When that creek rises, those apartments don't stand a chance. It’s a tragic, repetitive cycle that the Town Council has been trying to solve for decades with varying degrees of success.

It isn't just the creeks, though. It’s the infrastructure underneath your feet. Many of the pipes in the older parts of town—near UNC’s campus or the historic districts—were laid down when the population was a fraction of what it is today. They’re small. They’re old. Sometimes they’re partially blocked by decades of silt and debris. When you dump three inches of rain in an hour onto a system built for a 1950s drizzle, the math just doesn't work out.

The "Concrete Jungle" Effect

Every time a new apartment complex or parking deck goes up, the water has one less place to hide. Developers are now required to build retention ponds, which are those weird-looking dry pits you see behind shopping centers. They’re supposed to hold the water and let it out slowly. But here’s the thing: those ponds are designed based on historical data.

Climate change doesn't care about your history books.

🔗 Read more: How Did Black Men Vote in 2024: What Really Happened at the Polls

We are seeing "100-year floods" every five to ten years now. The data we used to build our drainage systems is increasingly obsolete. If you're living in Southern Village or near Eastgate Crossing, you’re essentially living in a target zone for the next big overflow.

Why Eastgate Crossing and Camelot Village are the Flashpoints

If you want to understand the stakes of Chapel Hill NC flooding, you have to look at Eastgate Crossing. It’s one of the busiest shopping centers in town. It’s also built on top of a swampy lowland where two creeks converge.

In 2013, and again during several tropical storms like Florence, Eastgate looked like a lake. Shop owners were literally rowing boats to get to their front doors. The town has spent a lot of money on the Lower Booker Creek Subwatershed Study to figure out how to stop this. They’ve talked about "wetland restoration" and "upsizing culverts." But those things take time and, more importantly, a staggering amount of taxpayer money.

The Human Cost of the Camelot Cycle

- Evacuations: Residents at Camelot Village have been evacuated by boat more times than most people have been to the beach.

- Insurance: If you live in these zones, flood insurance isn't just a suggestion; it’s a crushing monthly expense that keeps going up.

- Property Value: It’s hard to sell a condo when the disclosure form has to mention that the living room occasionally becomes a creek.

Honestly, it’s a mess. The town has even considered a "buyout" program, where they literally pay people to leave so they can tear the buildings down and let the land go back to being a natural floodplain. It’s a drastic move, but it might be the only permanent solution.

The UNC Factor: Can the University Save the Town?

The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill owns a massive amount of land. When UNC builds a new medical wing or a dorm, it changes the way water flows through the entire town. To their credit, the university has been aggressive about "green infrastructure."

You might have noticed permeable pavers around campus—those bricks with holes in them that let water soak into the ground. Or the cisterns hidden under the quads that catch rainwater to use for irrigation. These things help. They really do. But the university is an island in a sea of private development. Unless the town and the university are perfectly synced, one person's "green solution" just pushes the water onto someone else’s property.

💡 You might also like: Great Barrington MA Tornado: What Really Happened That Memorial Day

Small Scale vs. Large Scale

The town has a Stormwater Management Department. They’re the ones who have to deal with the angry phone calls when a basement floods in the Northside neighborhood. They focus on the little things:

- Clearing storm drains of autumn leaves.

- Fixing broken curbs.

- Ensuring construction sites have those black silt fences.

But these are band-aids. The real issue is the volume. Total, raw volume of water.

What Most People Get Wrong About Local Flooding

A common myth is that if you aren't in a "Flood Zone A" on a FEMA map, you’re safe. That’s just not true in Chapel Hill.

Because of the steep hills, we deal with something called "flash flooding." This isn't the slow rise of a river. This is a wall of water coming down a street because a culvert half a mile away got clogged with a discarded pizza box and some branches. You can be on high ground and still have your driveway washed away because the runoff from the neighbor's new patio had nowhere else to go.

The Hidden Threat: Saturated Ground

In North Carolina, we get "Precedential Rainfall." Basically, if it rains for three days straight, the red clay soil becomes like a soaked sponge. It can't hold another drop. Then, if a real storm hits on day four, 100% of that water stays on the surface. That’s when the Chapel Hill NC flooding gets dangerous. The ground gives up, and the water starts moving fast.

Practical Steps for Chapel Hill Residents

If you’re living here, you can’t just wait for the town to fix the entire drainage system. You have to be proactive. This isn't just about sandbags; it's about smart property management.

📖 Related: Election Where to Watch: How to Find Real-Time Results Without the Chaos

Check the Maps, but Don't Trust Them Blindly

Go to the Orange County GIS website. Look at the "Floodplain" layers. But also, look at the topography. If your house is at the bottom of a "V" shape on the map, you’re a drain. Even if FEMA says you’re fine, your backyard might say otherwise.

Redirect Your Downspouts

This sounds stupidly simple, but it’s the number one cause of wet basements. If your gutters dump water right next to your foundation, that water is going straight into your crawlspace. Buy those $10 plastic extensions and get the water at least six feet away from the house.

Plant a Rain Garden

If you have a soggy spot in your yard, don't fight it. Plant native NC grasses and shrubs that love "wet feet." Plants like Joe Pye Weed or River Birch can soak up hundreds of gallons of water that would otherwise head toward the street.

Get the Coverage

Most standard homeowners insurance does not cover flooding. You have to buy a separate policy through the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP). Even if you aren't in a high-risk zone, a "Preferred Risk Policy" is usually pretty cheap and can save you from financial ruin if a freak storm hits.

What to Watch in the Future

Keep an eye on the Town of Chapel Hill’s "Stormwater Capital Improvements Program." They have a list of projects—like the ones at Elliott Woods or Blue Meadow—that are designed to fix specific, chronic problem areas. If you live near one of these, go to the public meetings. Your input actually matters because you see how the water moves every time it pours.

The reality of Chapel Hill NC flooding is that it’s a permanent part of the landscape now. We can’t build our way out of it entirely, but we can definitely stop making it worse. It takes a mix of big-budget town engineering and individual homeowners making smart choices about their own plots of land.

Keep your gutters clean, watch the Bolin Creek water levels on the USGS gauges during storms, and maybe keep a pair of rubber boots in the trunk of your car. You're gonna need them.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Visit the NC Flood Risk Information System to see the specific risk level for your street address.

- Clear any debris from the storm drains near your house before a predicted heavy rain event to prevent street pooling.

- Contact the Chapel Hill Stormwater Management division if you notice significant erosion or standing water on public property that isn't draining after 48 hours.

- Inspect your crawlspace or basement for "efflorescence"—that white, powdery salt buildup—which is a surefire sign that water is seeping through your walls, even if you don't see a puddle.