You probably remember the "powerhouse of the cell" meme. Everyone knows mitochondria. But honestly? Centrioles in animal cells are the unsung heroes of your biological existence. They look like tiny pasta shapes—specifically rigatoni—floating near the nucleus, but without them, your body would basically fall apart at a microscopic level.

They’re small. They’re weird. And for a long time, biologists were kinda scratching their heads about whether they were even necessary for all life. It turns out, if you're an animal, they're non-negotiable.

What a Centriole in an Animal Cell Actually Does

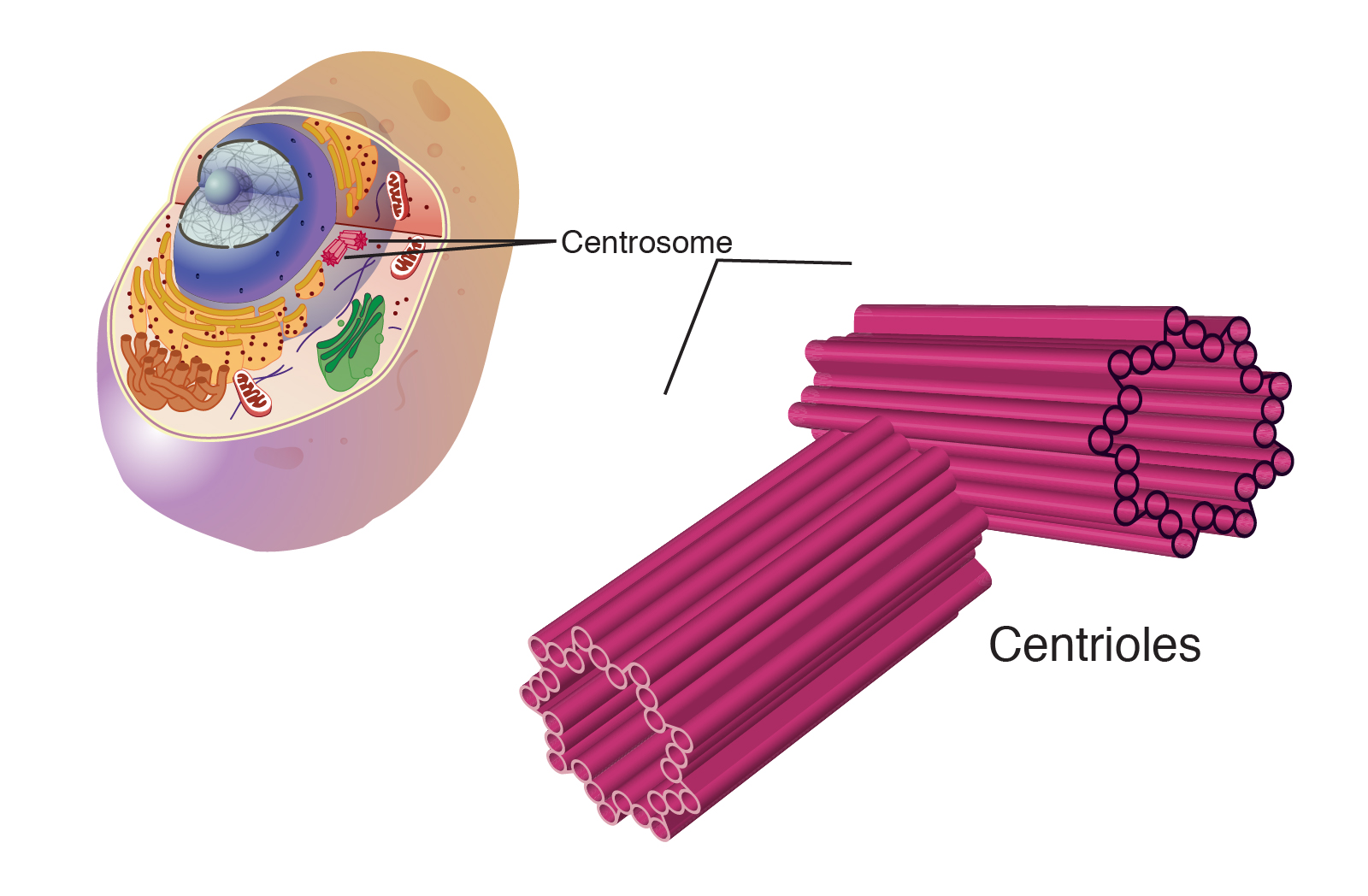

If you peek inside a typical animal cell, you’ll find two centrioles hanging out together. This duo is called a centrosome. Think of the centriole as the construction foreman of the cell. Their primary gig is organizing microtubules. These are the structural "beams" that give the cell its shape and act as a highway for moving stuff around.

But their big moment? Cell division.

When it's time for mitosis, these little barrels replicate and move to opposite ends of the cell. They start spinning out spindle fibers like a spider making a web. These fibers grab onto chromosomes and pull them apart so each new daughter cell gets the right amount of DNA. Without a functional centriole in an animal cell, this process gets messy. Fast. We’re talking about cells with the wrong number of chromosomes, which is a hallmark of cancer.

🔗 Read more: Can prenatal vitamins make your hair grow or is it just a myth?

The Architecture of a Microscopic Barrel

Nature loves the number nine. Every centriole is built from nine triplets of microtubules arranged in a perfect ring. It’s a geometric masterpiece. These microtubules are made of a protein called tubulin.

What’s fascinating is that they have a "mother" and a "daughter" centriole. The mother is older, obviously, and has these little appendages that the daughter lacks. This asymmetry isn't just for show; it helps the cell know which way is up. It’s a cellular compass. Researchers like Dr. Wallace Marshall at UCSF have spent years looking at how cells "count" and build these structures to such precise dimensions. It's not like the cell has a ruler. It's all chemical feedback loops.

Why Do Plants Get to Skip This?

This is where it gets spicy in the biology world. Most "higher" plants don’t have centrioles. They manage to divide just fine without them. So, why do we have them?

It boils down to motility. Centrioles are the base for cilia and flagella. Think about a sperm cell swimming or the tiny hairs in your lungs that clear out gunk. Those hairs are powered by a basal body, which is just a centriole that moved to the cell’s surface and started growing. Since plants don't usually have swimming sperm (with a few exceptions like mosses and ferns) or respiratory tracts, they evolved away from needing them. We didn't.

We need that specialized organization. Animal cells are more "squishy" and dynamic than plant cells with their rigid walls. We need the internal scaffolding that centrioles provide to keep things from collapsing during the violent physical act of splitting one cell into two.

When Centrioles Go Rogue: The Cancer Connection

In a healthy body, you have exactly two centrioles before they replicate for division. But in many cancer cells, you see way more. It’s called centrosome amplification.

Imagine trying to play a game of tug-of-war with three or four teams instead of two. The chromosomes get pulled in too many directions. Some get lost. Some get broken. This "chromosomal instability" allows cancer to evolve quickly and resist treatment.

Oncology researchers are currently looking at ways to target these extra centrioles. If we can find a drug that only kills cells with too many centrioles, we could theoretically wipe out cancer cells while leaving healthy ones alone. It's a "silver bullet" theory that's still in the works, but companies like Centrosome Therapeutics have poked at this for years.

✨ Don't miss: Can I Pee with a Tampon In? What Most People Get Wrong

The Mystery of De Novo Formation

For a long time, we thought centrioles could only come from other centrioles. Like a sourdough starter. You need a piece of the old one to make the new one.

Turns out, that's not strictly true.

If you laser-ablate (basically zap) the centrioles out of a cell, the cell can sometimes build new ones from scratch. This is called de novo formation. It’s a backup system. But it’s risky. Cells that make centrioles this way often mess up the count, leading back to those stability issues I mentioned earlier. It shows just how vital a centriole in an animal cell is—the cell will literally try to manifest them out of thin air if they go missing.

Moving Beyond the Textbook

Most people stop learning about centrioles after their 10th-grade biology quiz. That's a mistake. These structures are involved in signaling pathways that tell the cell when to grow and when to die. They are the "brains" of the cytoskeleton.

Recent studies have even linked centriole dysfunction to microcephaly and other developmental disorders. If the centrioles can't organize the microtubules properly during brain development, the stem cells can't divide enough to make a full-sized brain. It's a high-stakes job for a protein barrel that’s only 250 nanometers wide.

💡 You might also like: High Fiber Snack Foods Explained (Simply)

Quick Facts You Might Have Missed:

- Centrioles are almost always found in pairs at right angles to each other.

- They are absent in most fungi.

- The "9+0" or "9+3" arrangement refers to the specific count of microtubule bundles.

- They are roughly 0.2 micrometers in diameter. That's tiny. Like, "you need an electron microscope" tiny.

Actionable Steps for Further Exploration

If you're a student or just a science nerd, don't just take my word for it. The world of cell biology changes every time a better microscope is invented.

- Check out the Protein Atlas: Look up "Centriole" to see actual high-res imaging of where these proteins live in human tissue. It's way cooler than a drawing.

- Read up on Ciliopathies: If you want to see what happens when centrioles fail, look into diseases like Bardet-Biedl syndrome. It connects centriole health to everything from vision loss to kidney function.

- Follow Live-Cell Imaging: Search YouTube for "centrosome duplication live-cell imaging." Watching them spin out microtubules in real-time is honestly kind of hypnotic and makes the "static" textbook images feel prehistoric.

- Investigate Microtubule Inhibitors: If you're interested in medicine, look into how drugs like Taxol (used in chemotherapy) interact with the structures centrioles build. It’s a direct application of this "boring" biology.

Centrioles might not get the fame of DNA or the "cool factor" of CRISPR, but they are the literal anchors of animal life. They keep your cells organized, your DNA moving, and your body swimming. Pretty good for a bunch of protein tubes.