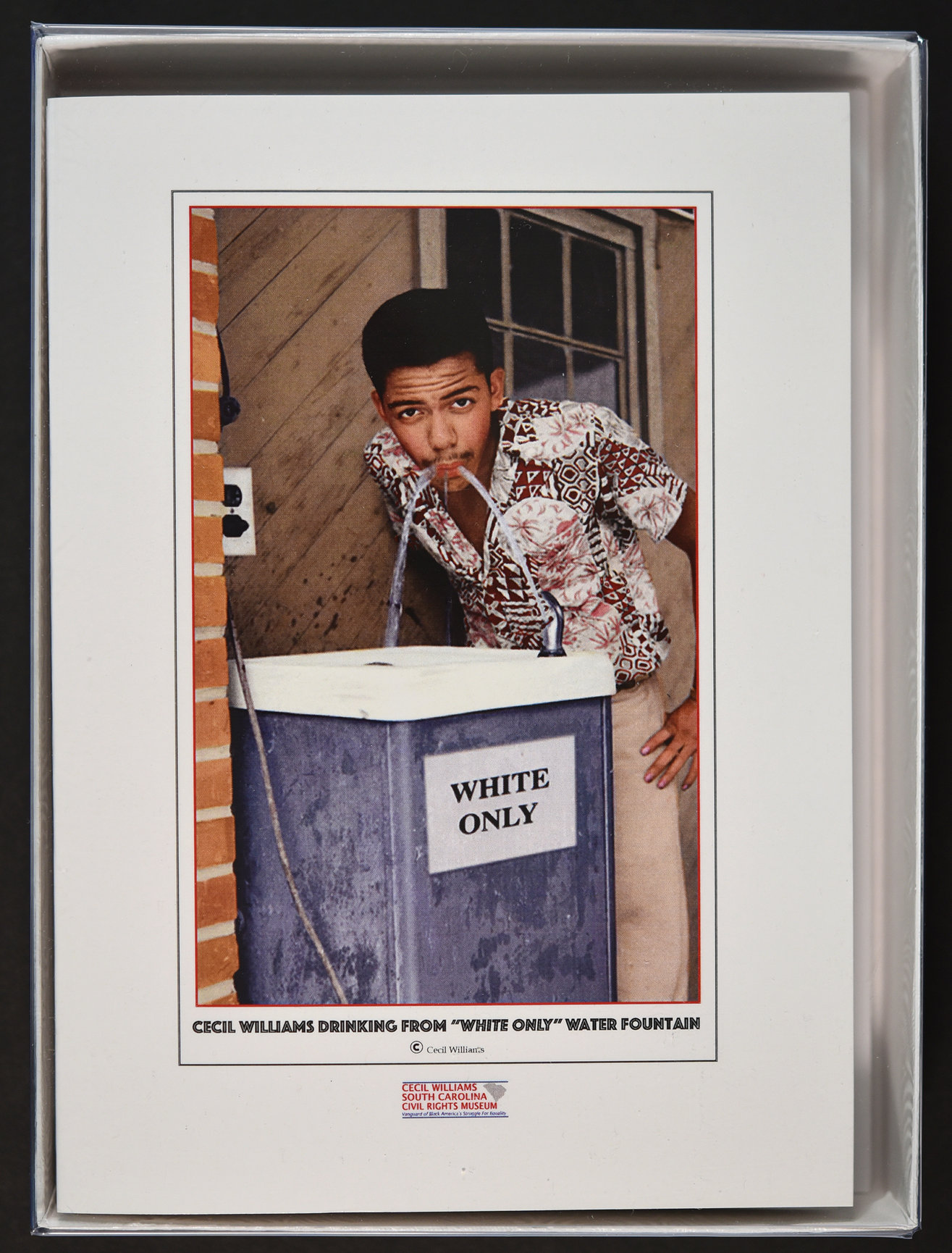

You’ve likely seen the photo. A young Black man in a sharp, unbuttoned Hawaiian shirt leans over a porcelain water fountain. His left hand, sporting a gold watch, rests coolly on his hip. Above the fountain, a crisp, professional-looking sign reads: WHITE ONLY.

It’s an image that stops your scroll. It feels modern, yet it’s from 1956. The man is Cecil Williams.

Most people assume this was a planned protest or a staged piece of activism meant for the front pages. Honestly, the truth is much more human. Cecil Williams was just thirsty.

The Story Behind the Cecil Williams Water Fountain Photo

It was a blistering summer day in South Carolina. Cecil Williams, then only 19 but already a veteran freelancer for Jet magazine, was driving back to Orangeburg with his friend Rendall Harper. They had been down on the coast, documenting the struggle to desegregate state beaches.

Basically, they were exhausted. They pulled into a service station on U.S. Route 21 near Walterboro.

✨ Don't miss: Candace Owens on Charlie Kirk: The Falling Out and the Theories That Split the Right

Williams didn't see a "Colored" fountain. He saw one fountain. It was marked for white people, but the station looked deserted, and his throat was parched. He didn't care about the rules in that moment; he just wanted a drink.

As he leaned in, the instinct of a photographer kicked in. He handed his camera to Harper. "Take this," he told him. Harper snapped the shot. Then they swapped places—Williams took a photo of Harper drinking, too.

Why the image looks "too good" to be true

If you spend any time on Reddit or history forums, you'll see people claiming the cecil williams water fountain photo is Photoshopped. They point to the "White Only" sign. It looks too clean. The lettering is too perfect.

But here’s the thing: it’s 100% real.

The reason it looks "fake" to modern eyes is often due to aggressive AI upscaling and colorization. People trying to "restore" the photo have smoothed out the grain, making the sign look like a digital overlay. In reality, those signs were mass-produced. They were off-the-shelf items for business owners, much like "No Smoking" signs are today.

Williams himself has addressed the skeptics. He’s explained that the station was unmanned at the moment, which is why he felt bold enough to do it. But he also admits it was dangerous. This was 1956. Emmett Till had been murdered just a year prior for far less.

🔗 Read more: What Really Happened With the Fatal Car Accident on Hwy 155 Today

A Life Behind the Lens

Cecil Williams wasn't just a guy at a fountain. He is a titan of civil rights documentation.

By the age of 14, he was the youngest photographer contributing to Jet. He wasn't just capturing moments; he was building an archive of a revolution. He was there for the prosecution of Briggs v. Elliott, the South Carolina case that helped pave the way for Brown v. Board of Education.

He photographed:

- Thurgood Marshall arriving in Charleston.

- The aftermath of the 1968 Orangeburg Massacre.

- The 1969 Charleston Hospital Strike.

- Personalities like Muhammad Ali and Jackie Robinson.

He wasn't just a witness. He was a target.

Williams grew up in a world where the library, the playground, and the dressing rooms were all off-limits. His parents were limited to being a teacher and a tailor because Jim Crow didn't allow for much else. He used his camera as a shield and a weapon.

The Fountain Today: A Legacy in Orangeburg

For decades, that photo sat undeveloped or tucked away. Williams didn't even publish it until 2006 in his book Out-of-the-Box in Dixie. He didn't think it was his most "important" work at the time. He was focused on the marches and the courtrooms.

But the internet changed that.

The image went viral because of its vibe. It’s not a photo of a victim; it’s a photo of a man reclaiming his dignity through a simple act of defiance. Today, that "forbidden" drink is a centerpiece of the Cecil Williams South Carolina Civil Rights Museum in Orangeburg.

💡 You might also like: Who Won the Presidential Debate Tonight? Why Nobody Can Agree

Visiting the Museum

The museum isn't a corporate, polished hall. It’s personal. It’s located at 1865 Lake Drive.

Inside, there is a physical replica of that water fountain. Visitors often stand behind it, mimicking Williams’ pose. It’s become a rite of passage for students and activists.

You can also buy high-quality prints of the original photo there. Williams, now in his late 80s, still works to preserve the million-plus images in his collection. He’s currently the Director of Historic Preservation at Claflin University, overseeing the digitization of their archives.

Actionable Insights for History Enthusiasts

If you're interested in the real history of the movement beyond the textbook highlights, here's how to engage with Cecil Williams' work:

- Visit the Museum: If you're near Orangeburg, go. It’s the only museum of its kind in the state.

- Look for the Book: Check out Injustice in Focus: The Civil Rights Photography of Cecil Williams by Claudia Smith Brinson. It’s the definitive biography and includes over 80 of his most vital shots.

- Verify the Source: When you see the water fountain photo online, look for the grain. If it looks like a 4K Pixar movie, it’s been over-processed. Seek out the original black-and-white versions to see the raw texture of 1956.

- Support the Archive: The museum is a 501(c)3. Preserving these physical negatives is expensive and vital for future generations.

The cecil williams water fountain story reminds us that history isn't always made of grand speeches. Sometimes, it’s just a thirsty teenager deciding that a sign isn't going to stop him from having a drink of water.

Check the museum's website for current exhibition hours and upcoming talks. Williams often participates in events, especially during Black History Month, and hearing the stories directly from the man who lived them is an experience you won't get from a screen.