When you look at a catholic church popes list, you aren't just looking at a directory of religious leaders. It is a messy, sprawling, and sometimes chaotic record of Western civilization itself. People often think the line is this perfect, unbroken chain of 266 men, all perfectly holy and sequentially sorted. Honestly, it's way more complicated than that. History is rarely as clean as a PDF download from the Vatican website.

Think about it. We have periods where there were two popes. Sometimes three. There were moments when the papacy was essentially bought by wealthy families in Rome, and other times when the "Pope" was a 20-year-old with zero interest in theology.

The total count is a bit of a headache

If you ask the Annuario Pontificio—the official papal yearbook—they’ll tell you Pope Francis is number 266. But that number is a bit of an "educated guess" in some places. Why? Because the early centuries are murky. St. Peter is obviously the starting point. Nobody disputes that. But the guys immediately after him, like Linus, Cletus, and Clement? We’re relying on early historians like Irenaeus and Eusebius, who were writing decades or even centuries after the fact.

The catholic church popes list has actually changed over time. For a long time, there was a Pope Stephen II who died three days after his election before he could be consecrated. He was on the list for centuries. Then, in 1961, the Vatican decided he shouldn't count because he hadn't undergone the proper ceremony. They bumped him off. Suddenly, every Stephen after him had to have their "number" adjusted in the history books. It’s a clerical nightmare.

The "Anti-Pope" problem

You can't talk about the list without talking about the guys who tried to steal the job. An "antipope" is someone who makes a significant claim to be the Bishop of Rome but isn't recognized by the Church as the legitimate one. During the Western Schism (1378–1417), the situation got so ridiculous that you had one pope in Rome, one in Avignon (France), and eventually a third one in Pisa.

Imagine being a peasant in the 1400s. You’re just trying to get to heaven, and you have three different men all claiming to be the Vicar of Christ and excommunicating each other. It was a total mess.

🔗 Read more: Marie Kondo The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up: What Most People Get Wrong

- Hippolytus of Rome is arguably the first antipope.

- He actually ended up being a saint because he reconciled with the real pope while they were both being worked to death in the Sardinian salt mines.

- Alexander VI (the Borgia pope) stayed on the legitimate list despite being... well, not exactly a "holy" man by most standards.

Legitimacy usually comes down to who was elected by the proper college of cardinals at the time, but in the first millennium, it was often about who had the support of the Roman mobs or the Byzantine Emperor.

Names and why they matter

Notice how nobody ever picks "Peter II"? It’s considered an unwritten rule. Out of respect for the first apostle, no pope has ever taken the name Peter. If a guy named Peter gets elected, he usually switches it up. Like Pope Sergius IV—his birth name was Pietro, but he changed it because he didn't want to be the guy to challenge the original.

John is the most popular name. There have been 21 Johns, but the numbering goes up to 23. Wait, what? Yeah, there was no John XX. It was a counting error in the middle ages that just never got fixed. Everyone just skipped it. And then there’s the "John XVI" who was an antipope, but they kept his number anyway for the next guy. It’s these little glitches that make the catholic church popes list feel human. It’s a record of people, and people make mistakes.

The era of the "Pornocracy"

This is a real term used by historians (the Saeculum obscurum). In the 10th century, the papacy was basically a puppet for the Theophylacti family. The list during this time is wild. You had Pope John XI, who was allegedly the illegitimate son of Pope Sergius III. You had violent deaths, backstabbing, and popes being thrown into dungeons.

If you think modern politics is toxic, read about the Cadaver Synod. Pope Stephen VI literally dug up the corpse of his predecessor, Pope Formosus, put the rotting body on a throne, and put it on trial. He found the corpse guilty, chopped off its blessing fingers, and threw it in the Tiber.

💡 You might also like: Why Transparent Plus Size Models Are Changing How We Actually Shop

Stephen was eventually strangled in prison. This is the stuff that makes the official list so fascinating. It isn't just a list of saints; it's a list of survivors, sinners, and occasional geniuses.

How the modern list is formed

Today, it's much more regulated. The Sede Vacante (the period when the chair is empty) triggers a Conclave. The doors are locked. Extra omnes. No phones, no internet, just a bunch of guys in red hats voting until white smoke appears.

But even recent history has its quirks.

- Pope John Paul I only lasted 33 days in 1978.

- His death was so sudden it sparked a million conspiracy theories, though it was almost certainly a heart attack.

- Then came John Paul II, the first non-Italian in 455 years.

- And then Benedict XVI, who did the unthinkable and resigned.

Benedict's resignation changed the list forever. It proved that the papacy isn't a life sentence if the person isn't physically up to the task anymore. It moved the office from a medieval kingship into a modern functional role.

The geographical shift

For most of the last millennium, the catholic church popes list was a list of Italians. Specifically, Italians from a few noble families. Medici, Borgia, Orsini. But if you look at the early list, it was global. You had Greeks, Syrians, and Africans like Pope Victor I or Pope Miltiades.

📖 Related: Weather Forecast Calumet MI: What Most People Get Wrong About Keweenaw Winters

We are seeing a return to that. Pope Francis, being from Argentina, represents a shift toward the Global South, where the majority of Catholics actually live today. The list is becoming less of a European "who's who" and more of a global representation.

What should you actually do with this information?

If you are researching the catholic church popes list for a project, or just because you’re a history nerd, don’t just look at the names. Look at the gaps. Look at the years 1268 to 1271—there was no pope for nearly three years because the cardinals couldn't agree. The locals eventually got so fed up they ripped the roof off the building and started rationing their food to "encourage" a decision.

Next steps for deeper research:

- Check the "Liber Pontificalis": This is the ancient "Book of the Popes." It’s the primary source for the early names, but keep in mind it’s biased and often legendary in its descriptions of the first few centuries.

- Cross-reference with Secular History: When you see a pope on the list, look at who was the Holy Roman Emperor or the King of France at the same time. The tensions between those two usually explain why certain popes were elected.

- Investigate the "Great Schism": If you want to see how the list was almost destroyed, read about the Council of Constance. It's the only reason we have a single, unified list today.

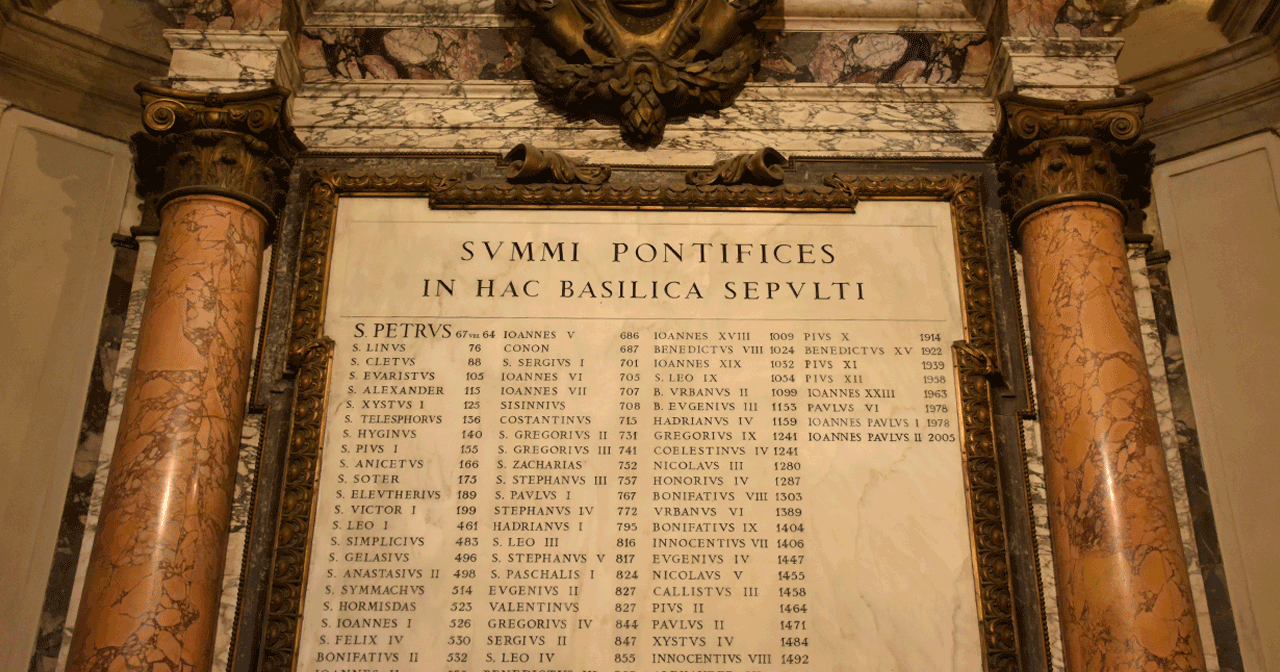

- Visit the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls: If you're ever in Rome, they have mosaic medallions of every single pope in a long line around the interior. There are only a few empty spots left. It’s a physical, visual version of the list that really puts the scale of 2,000 years into perspective.

The papacy is the oldest continuous institution in the Western world. Whether you're religious or not, the list is the backbone of history. It survived the fall of Rome, the Black Death, the Reformation, and two World Wars. It’s not just a list of names; it’s a timeline of how we got here.