Ever looked at a calico and wondered why they’re almost always girls? Or why your neighbor’s "black" cat suddenly looks rusty brown after a nap in the sun? It’s wild. Cat colors and patterns aren't just random splashes of paint; they’re a complex, beautiful map of genetics that has been shifting for thousands of years. Honestly, most of what we think we know about how a cat gets its coat is just scratching the surface.

Genetics is a messy business. You’ve got dominant genes, recessive ones, and "masking" genes that act like a coat of primer over a wall. Basically, every cat is technically a tabby under the hood. It sounds fake, but it's true. Whether you’re looking at a sleek midnight panther or a splotchy tortoiseshell, the blueprints for those stripes are tucked away in their DNA, even if you can’t see them.

The Secret Base Layer of All Cat Colors and Patterns

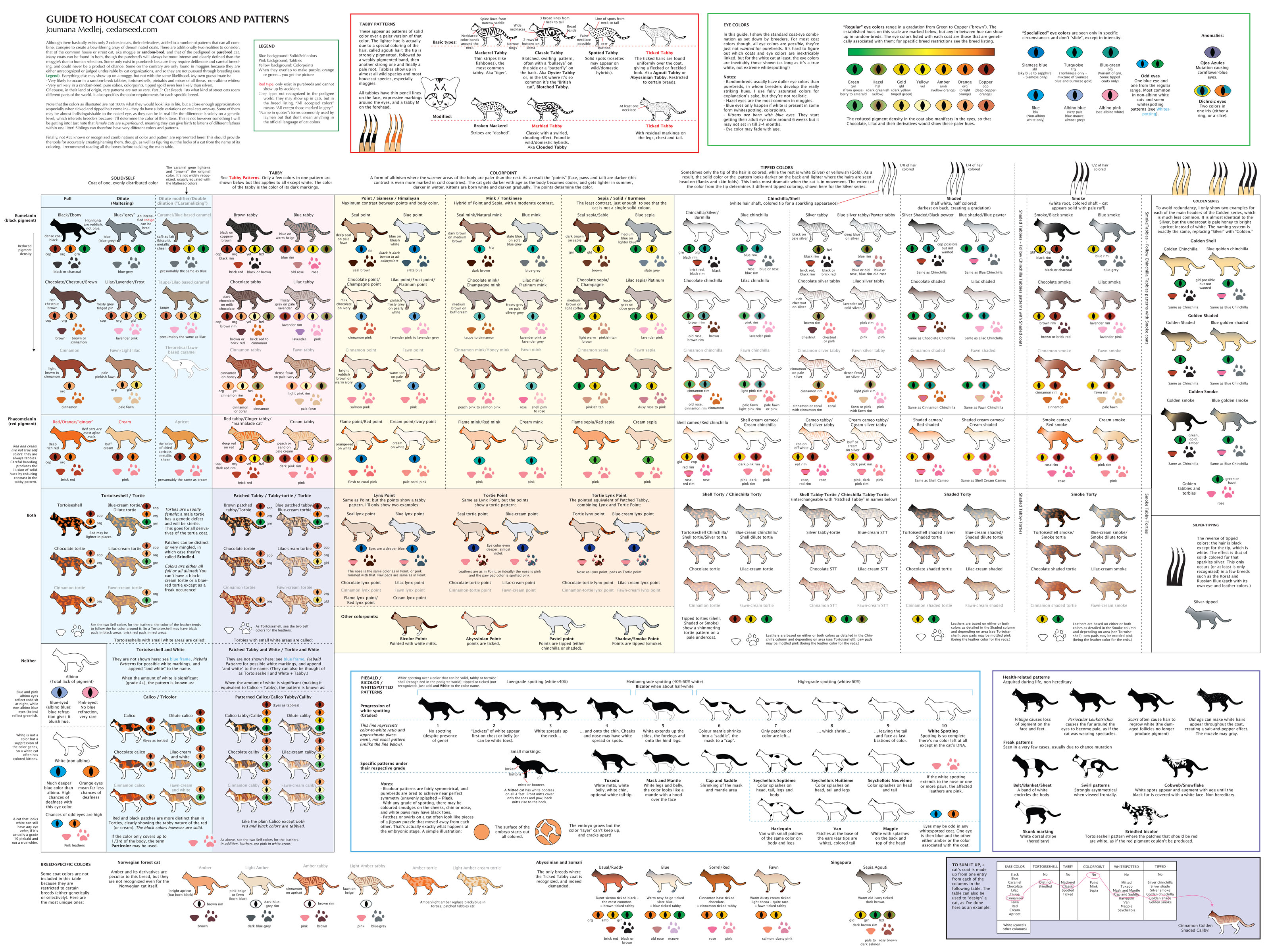

Let's get one thing straight right away: cats only really have two base colors. That’s it. Black and red. Every single variation you see—from the creamy lilac of a British Shorthair to the deep chocolate of a Havana Brown—is just a modification of those two pigments.

The pigment responsible for black is eumelanin. The one for red (or orange/ginger) is phaeomelanin. When you see a "blue" cat, like a Russian Blue or a Chartreux, you’re actually looking at a black cat whose pigment granules have been clumped together differently. This is caused by the dilution gene (d). It’s like taking a bucket of dark paint and stirring in a bunch of water; the color stays the same chemically, but it hits the eye differently.

Why the Ginger "M" Matters

If you have an orange cat, look at their forehead. You’ll see that "M" shape. This is the mark of the tabby. While some solid black cats can hide their tabby stripes (thanks to the non-agouti gene), the red pigment is stubborn. It refuses to be suppressed. This is why almost all orange cats show at least some faint stripes or "ghosting." They just can’t help it.

Interestingly, about 80% of orange tabby cats are male. This isn't a coincidence or a myth. The gene for "red" is carried on the X chromosome. Since males are XY, they only need one "red" gene from their mom to turn orange. Females are XX, so they need it from both parents. If they only get it from one, they end up as a tortoiseshell. It's a game of chromosomal loto.

The Chaos of White Spotting and Albinism

White isn't actually a "color" in the feline world. It’s more like a lack of color. When you see a cat with white paws (mittens) or a white chest (a locket), you’re seeing the work of the KIT gene. This gene determines how pigment cells migrate while the kitten is still a tiny embryo in the womb.

👉 See also: Why People That Died on Their Birthday Are More Common Than You Think

If the cells don’t make it all the way to the extremities, the cat ends up with white feet, a white tail tip, or a white snout.

- Van Pattern: This is the extreme end. The cat is almost entirely white, with color only on the head and tail.

- Bi-color: Roughly half and half. Think of the classic "tuxedo" cat.

- Mitted: Just the paws. Very common in Ragdolls.

Then there’s the Dominant White gene (W). This is a bit more intense. It essentially masks every other color the cat might have. A solid white cat could genetically be a black tabby, but the W gene acts like a heavy white tarp thrown over the whole thing. There’s a well-documented link between this gene and deafness, specifically in blue-eyed white cats. According to the Cornell Feline Health Center, about 65% to 85% of all-white cats with two blue eyes are deaf. If they have only one blue eye, they might only be deaf in the ear on that side.

Tabby Variations You Probably See Every Day

The "tabby" is the OG cat pattern. It’s the camouflage of the African Wildcat (Felis lybica), the ancestor of our couch-dwelling friends. But not all tabbies are created equal.

The Mackerel Tabby is what people usually call a "tiger cat." We’re talking thin, vertical stripes running down the sides. It’s the most common pattern in the global cat population.

Then you have the Clogged or Blotched Tabby, often called the "Classic" tabby. Instead of thin lines, they have thick swirls and "bullseye" marks on their flanks. It’s a mutation that became incredibly popular in the UK and Iran centuries ago.

The Ticked Tabby is the weirdest one. Think of an Abyssinian. At first glance, they don't look like tabbies at all. But if you look at an individual hair, it’s "agouti"—meaning it has bands of different colors on a single strand. They usually only have stripes on their face and maybe their legs.

✨ Don't miss: Marie Kondo The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up: What Most People Get Wrong

The Temperature-Sensitive "Pointed" Coats

This is where the science gets really cool. Siamese, Birman, and Himalayan cats have what we call "pointed" patterns. This is actually a form of partial albinism caused by a mutation in the tyrosinase gene.

This enzyme is temperature-sensitive. It only produces pigment in the cooler parts of the body. That’s why their ears, paws, and tails (the extremities) are dark, while their warm torso stays creamy or white.

If you were to shave a Siamese cat and put a cold pack on its back, the hair would technically grow back darker in that spot. (Please don't actually do that, though.) It’s also why Siamese kittens are born pure white; the womb is a consistent, cozy temperature, so the pigment never gets the signal to "turn on" until they hit the outside air.

Tortoiseshells, Calicos, and the Genetic "Off" Switch

People get confused between Torties and Calicos all the time. It’s simple:

- Tortoiseshells are a mix of black and red (or their diluted versions, blue and cream) swirled together. They have almost no white.

- Calicos are the same, but they have distinct white patches.

The presence of white actually changes how the other colors behave. In a tortoiseshell, the black and orange are finely brindled. But once you add the white spotting gene, it signals the other colors to "clump" together, resulting in those big, bold patches of orange and black.

This phenomenon is called X-inactivation or "Lyonization." Since females have two X chromosomes, the body has to "turn off" one in every cell to prevent a toxic overdose of gene products. In a calico, some cells turn off the "black" X, and others turn off the "orange" X. This happens randomly across the skin, creating a living, breathing mosaic.

🔗 Read more: Why Transparent Plus Size Models Are Changing How We Actually Shop

Rare Patterns Most People Never See

While we're all used to the neighborhood stray's markings, some patterns are incredibly rare.

The Lykoi (the "Werewolf Cat") has a unique "roan" coat, where white and colored hairs are interspersed, but it’s not due to the usual grey or dilute genes. It’s a natural mutation that affects the hair follicle, often leaving them with no undercoat and patchy fur around the eyes and muzzle.

Then there’s the Smoke pattern. A smoke cat looks solid until they move or you part their fur. The bottom half of the hair shaft is stark white, while the tip is deeply colored. It’s a stunning effect, often seen in Persians and Maine Coons, caused by the Inhibitor gene (I) which suppresses the development of pigment at the base of the hair.

Why Does My Black Cat Turn Brown?

This is a common "lifestyle" question for cat owners. If your black cat spends all day in the window, they might "rust." This is usually because the sun bleaches the eumelanin in their fur.

However, if your cat isn't a sunbather and they’re turning a dusty reddish-brown, it could be a nutritional issue. Specifically, a deficiency in tyrosine. This amino acid is required to create black pigment. Without enough of it in their diet, their coat can’t maintain its dark hue. It’s always worth checking the quality of their kibble if their color starts shifting unexpectedly.

How to Identify Your Own Cat's Pattern

Don't just say your cat is "grey." Be specific. Use the "Part-Color" rules. If they have white, they are a Bi-color. If they have three colors, they are a Calico or a "Tortie-and-white."

Check the tail. Is it ringed? That’s a tabby trait. Look at the nose leather. Is it pink, black, or "freckled"? Red cats often get black freckles (lentigo) on their noses and lips as they age. It’s totally harmless and just a quirk of the phaeomelanin pigment.

Actionable Steps for Future Cat Owners

- Check for Hearing: If you are adopting an all-white cat with blue eyes, perform a simple sound test (like clapping behind them) to see if they respond. Understanding their hearing status early helps you keep them safe, especially regarding outdoor access.

- Monitor Coat Changes: Sudden changes in coat color or texture in adult cats can signal health issues. "Rusting" can be a tyrosine deficiency, while a dull, greasy coat can indicate kidney issues or an inability to groom due to arthritis.

- Skin Protection: Light-colored cats, especially those with white ears and noses, are highly susceptible to squamous cell carcinoma (skin cancer). If your white-eared cat loves the sun, talk to your vet about pet-safe sunscreens or limiting their window time during peak UV hours.

- Genetic Testing: If you're genuinely curious about what lies beneath your cat's fur, kits like Basepaws or Wisdom Panel can identify the specific recessive genes your cat carries. This is particularly fun for "mystery" rescues.

- Grooming Specifics: Remember that different patterns often correlate with different fur types. Ticked coats (like Abyssinian) are often shorter and coarser, while the dilute colors (like "blue" or "lilac") can sometimes have a softer, plushier texture that matts differently than dense black fur.

Understanding the "why" behind your cat's look doesn't just make you a more informed owner; it connects you to the deep evolutionary history of a species that transitioned from desert hunters to our best friends. Every spot, stripe, and patch is a little piece of a genetic puzzle that started thousands of years ago.