The air was thick. Not just with the humid, pre-dawn fog of a Mississippi spring, but with the smell of coal smoke and the heavy vibration of a 4-6-0 Ten-Wheeler screaming down the tracks at speeds it was never really meant to hit. Most people know the name Casey Jones from the folk songs or the Grateful Dead lyrics, but the actual Casey Jones train crash wasn’t some psychedelic trip or a fictional moral tale. It was a terrifying, loud, and metallic mess that happened because a man was trying to do his job too well.

It was April 30, 1900. 3:52 a.m.

John Luther "Casey" Jones was pushing Engine No. 382 toward a curve near Vaughan, Mississippi. He was a legend for punctuality. Honestly, he was obsessed with it. That night, he was pulling the "Cannonball Express," and he was behind schedule. For a guy like Casey, being late was basically a sin. He had his hand on the throttle, eyes peering through the dark, trying to make up 75 minutes of lost time on a run from Memphis to Canton. He almost made it, too.

The Setup for Disaster at Vaughan Siding

Railroading in 1900 was a different beast. There were no digital sensors, no GPS, and no automatic braking systems. You had your watch, your orders, and your ears. Casey had just taken over the run as a favor for a sick friend, Sam Tate. He’d already put in a full shift, meaning he was likely exhausted, but he was "highballing"—railroad slang for going full tilt.

The math was working in his favor until it wasn't. He had managed to claw back almost all the lost time. As he approached Vaughan, he was only about two minutes behind. But there was a massive problem sitting right on the main line.

Three trains were already at the Vaughan station. Two freights, No. 72 and No. 83, were trying to get into a siding to let Casey pass. But the siding wasn't long enough. They were "sawing by"—a tedious process of moving trains back and forth to clear the main track. While they were doing this, an air hose broke on one of the freights. The brakes locked. Four cars of the other freight train were left dangling out onto the main line, right in Casey's path.

🔗 Read more: Map of the election 2024: What Most People Get Wrong

The Moment of Impact: "Jump, Sim, Jump!"

Sim Webb, Casey’s fireman, was the only other person in that cab. He was the one shoveling the coal, keeping the "old girl" hot so Casey could hit those 70-plus mph speeds. As they rounded the blind curve at Vaughan, the red lights of a caboose suddenly flared into view through the fog.

Webb saw it first.

He screamed at Casey. Casey stood up, grabbed the air brake, and threw it into emergency. He reversed the engine. He did everything the manual said to do, and then some. But physics is a cruel mistress when you're moving 100 tons of steel at high speed.

"Jump, Sim, jump!" Casey yelled.

Webb didn't argue. He braced himself and leaped into the darkness, hitting the ground and knocking himself unconscious. Casey stayed. He stayed with his hand on the brake and his other hand on the whistle cord, screaming a warning to anyone near the tracks.

💡 You might also like: King Five Breaking News: What You Missed in Seattle This Week

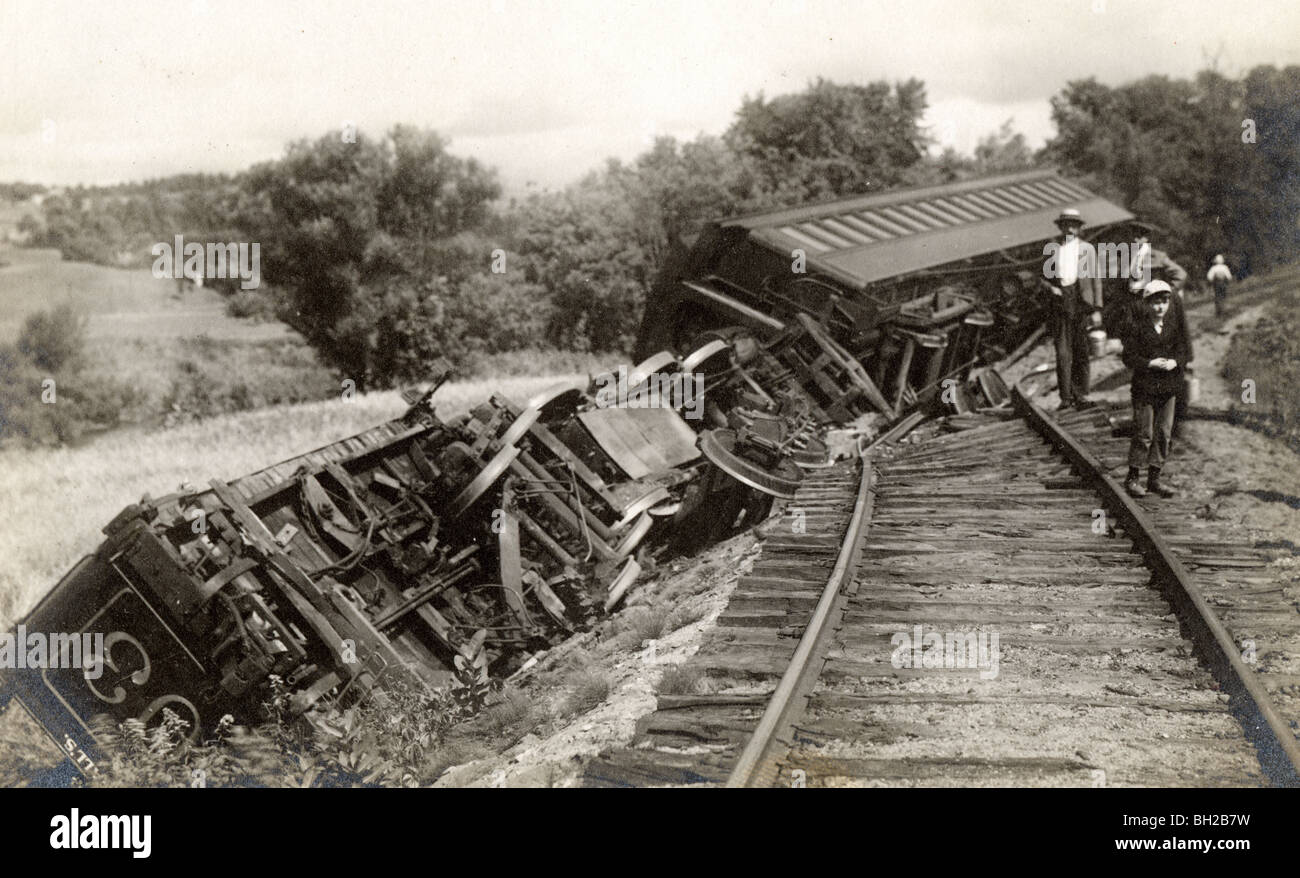

The crash was catastrophic. No. 382 plowed through the caboose, then through a car full of hay, a car of corn, and halfway into a car of lumber. When they found Casey, he was dead under the wreckage. But here’s the kicker: he was the only one. Because he stayed to slow the train down, every single passenger survived with nothing more than a few bumps and bruises.

Was It Actually Casey’s Fault?

The official Illinois Central Railroad report didn't hold back. They blamed Casey. They claimed he ignored a flagman named John Newberry who was supposed to be out on the tracks with "torpedoes"—small explosive caps that would pop when a train ran over them to warn the engineer of danger.

The report said Casey simply didn't listen. But Sim Webb, who lived until 1957, went to his grave swearing they never saw a flagman and never heard a torpedo.

The Evidence Against the Official Story:

- The Fog: Visibility was garbage that night. Even if Newberry was out there, the curve and the mist could have hidden his lamp.

- The Siding Mess: The freight trains were performing a "saw-by" maneuver that was technically a violation of safety protocols for a fast mail train's right-of-way.

- Fatigue: Casey had been working for nearly 14 hours straight. Even a legend gets tired.

Beyond the Legend: What Most People Get Wrong

People think the Casey Jones train crash was a freak accident. It wasn't. It was a systemic failure. The tracks were light, the trains were getting heavier, and the schedules were becoming impossible. Casey was just the guy who became the face of it because a black engine-wiper named Wallace Saunders wrote a song about him.

Saunders knew Casey. He liked him. He turned Casey’s death into a ballad that spread through the rail yards like wildfire. Eventually, professional songwriters stole the tune, cleaned it up, added some "vaudeville" flair, and turned a tragedy into a pop culture staple.

📖 Related: Kaitlin Marie Armstrong: Why That 2022 Search Trend Still Haunts the News

The "Cannonball" wasn't even the name of the train; it was a nickname for the fast mail run. And No. 382? It was actually a "jinxed" engine. After Casey died, it was rebuilt and crashed multiple times, killing several other railroaders before finally being scrapped in 1935.

Actionable Insights for History Buffs

If you're looking to dig deeper into the real history of the 1900 wreck, skip the folk songs for a second and look at the logistics.

- Visit the Scene: You can actually visit the Casey Jones Home and Railroad Museum in Jackson, Tennessee. They have a sister engine to the 382 there.

- Read the Testimony: Look up the original 1900 IC Accident Report. It’s a fascinating look at how corporations handled liability over a century ago.

- Check the Timeline: Compare Sim Webb’s 1950s recorded interviews with the 1900 report. The discrepancies tell you everything you need to know about "official" history versus survivor reality.

To understand the Casey Jones train crash, you have to stop looking at him as a superhero and start looking at him as a man caught between a deadline and a disaster. He chose to stay at his post when he could have jumped. That doesn't make him a myth; it makes him a person who made a very hard choice in a split second.

Explore the official records at the Water Valley Casey Jones Museum or look into the archives of the Brotherhood of Locomotive Engineers to see how union safety standards changed specifically because of wrecks like this one.