If you could hop into a time machine and land on a street corner in 1926, you’d probably be terrified. It wasn't the "quaint" experience people imagine. It was loud. It was incredibly smelly. Honestly, the traffic was a total disaster because nobody really knew who had the right of way yet. Cars 100 years ago weren't just primitive versions of what we drive today; they were part of a massive, chaotic social experiment that was currently exploding across the globe.

1926 was a pivot point.

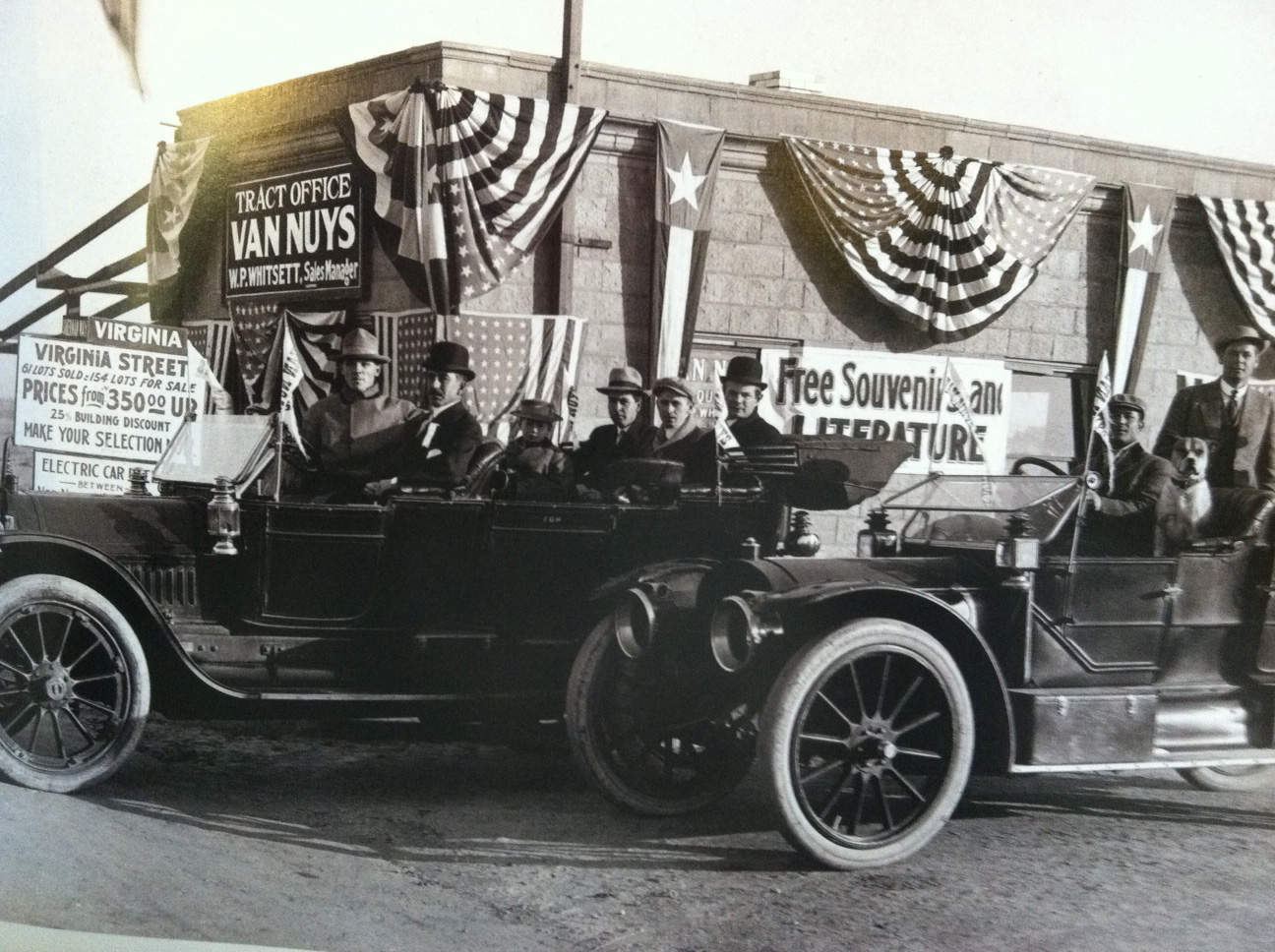

The industry was moving away from "horseless carriages" and toward the recognizable machines we see in black-and-white movies. But the transition was messy. You had hundreds of manufacturers—names like Packard, Hudson, Studebaker, and Duesenberg—all fighting for a market that was rapidly shifting from a luxury playground for the rich to a basic necessity for the middle class.

The Ford Problem and the Death of the Model T

By 1926, the legendary Model T was basically a zombie. It was still walking, but it was effectively dead. Henry Ford had built over 13 million of them by this point, and while they had "put the world on wheels," they were hopelessly outdated.

Imagine trying to drive a car today where the throttle is a lever on the steering wheel and the "transmission" is a series of floor pedals that don't do what you think they do. That was the Model T. While competitors like Chevrolet (owned by GM) were starting to offer "modern" luxuries—things like electric starters, varied colors, and three-speed sliding gear transmissions—Ford was still stubbornly clinging to his 1908 design.

Chevy was eating Ford's lunch.

General Motors, under Alfred P. Sloan, figured out something Ford didn't: people wanted to feel special. They introduced the "annual model change." This was a massive shift in how business worked. Instead of one car that stayed the same forever, they gave you something new to buy every year. By the middle of 1926, the writing was on the wall. Ford’s market share was cratering, and the Highland Park plant was feeling the pressure. It’s kinda wild to think that the most successful car in history was becoming a joke just because it didn't have a gas gauge or a standard gear shift.

Roads were basically mud pits

We talk about cars 100 years ago, but we rarely talk about where they actually drove. In 1926, the U.S. Federal Highway System was only just being officially organized. The "U.S. Route" shield signs we see everywhere now? Those were adopted in November 1926. Before that, if you wanted to drive from New York to Chicago, you were basically following "auto trails" marked by colored bands on telephone poles.

It was brutal on the machinery.

🔗 Read more: I Forgot My iPhone Passcode: How to Unlock iPhone Screen Lock Without Losing Your Mind

Tires didn't last 50,000 miles. You were lucky to get 3,000 miles before a blowout. Because most roads were unpaved or poorly graveled, dust was a constant nightmare. This is why "motoring" required a specific outfit—dusters, goggles, and hats. It wasn't a fashion statement; it was survival gear so you didn't arrive at your destination looking like a coal miner.

Technology that felt like sorcery (and some that was just dangerous)

In 1926, several "modern" features were actually starting to trickle down to the average buyer. Ethyl gasoline (leaded gas) had been introduced a few years prior by Thomas Midgley Jr. at General Motors. At the time, it was hailed as a miracle because it stopped engines from "knocking." We know now it was a public health catastrophe, but back then, it was the cutting edge of chemical engineering.

Mechanical four-wheel brakes were also becoming a big deal.

Up until the mid-20s, many cars only had brakes on the rear wheels. Think about that for a second. You're driving a 3,000-pound hunk of steel at 45 mph, and you only have stopping power on two tires. In 1926, Buick and Packard were pushing four-wheel systems, making driving significantly less suicidal.

The Rise of the Closed Car

This is a detail most people miss: 1926 was roughly the year where closed cars (sedans with a solid roof) finally outsold open cars (roadsters and touring cars). Before this, "closed" cars were expensive luxury items because building a wooden frame strong enough to hold heavy glass windows without shattering was hard.

But by '26, steel stamping technology improved.

Suddenly, you could drive in the winter without freezing your face off. This changed everything. It turned the car from a summertime toy into a year-round tool. It meant people could move further from city centers, kickstarting the very first real wave of suburbanization.

What it was actually like to sit in the driver's seat

The ergonomics were a nightmare. Honestly, they were.

💡 You might also like: 20 Divided by 21: Why This Decimal Is Weirder Than You Think

There was no power steering. You needed actual upper-body strength to turn a car at low speeds. The steering wheels were massive—often made of wood—to give the driver enough leverage to move the wheels. There was no heater. If it was cold, you put a blanket over your legs or used a "foot warmer" which was essentially a metal box filled with hot coals or heated bricks.

- Starting the car: If you didn't have an electric starter (which many cheaper cars still lacked), you had to use a hand crank at the front. If the engine kicked back, it could literally break your arm. This happened so often it was called a "Ford fracture."

- The Smell: Everything smelled like unburnt hydrocarbons, hot oil, and horse manure. Remember, horses were still all over the streets in 1926. The transition wasn't instant.

- The Speed: Most cars topped out around 40-50 mph, but the roads usually wouldn't let you go faster than 25 mph without losing a kidney to the bumps.

The Duesenberg Factor

While the average person was putting around in a Chevy Superior or a Willys-Overland, the ultra-rich were entering a golden age. The Duesenberg Motors Company was struggling financially in 1926, which led to its purchase by Errett Lobban Cord. This move eventually gave us the Model J, but even in '26, the Duesenberg straight-eight engines were works of art. These cars were hitting speeds over 80 mph when the average person was lucky to hit 30. It was the equivalent of driving a Bugatti Chiron in a world full of used Nissan Altimas.

The Business of 1926: Consolidate or Die

The "Big Three" (GM, Ford, Chrysler) weren't fully solidified yet, but the squeeze was on. Walter Chrysler had just launched the Chrysler Corporation in 1925, and by 1926, he was aggressively expanding. He realized that to survive, you couldn't just sell one car; you needed a "brand for every purse and purpose," a philosophy he shared with GM.

The small guys were disappearing.

Names like Apperson, Flint, and Rickenbacker (started by the WWI ace Eddie Rickenbacker) were either folding or on their last legs. The cost of machinery to stamp steel bodies was so high that if you weren't selling tens of thousands of cars, you couldn't afford to stay in the game. It was the end of the "tinkerer" era and the start of the corporate industrial era.

Real-world impact: How the car changed 1926 society

The "Sunday Drive" became a cultural phenomenon.

Because cars were now reliable enough to leave the city, "roadside architecture" started to appear. The very first motels (a portmanteau of "motor hotel") were popping up. Gas stations were evolving from simple curbside pumps to actual buildings with bathrooms and snacks.

It also changed dating.

📖 Related: When Can I Pre Order iPhone 16 Pro Max: What Most People Get Wrong

Sociologists at the time were genuinely worried about the "rolling parlor." Before the car, if a young man wanted to see a young woman, he had to sit in her family's living room under the watchful eye of her parents. With a car? They could just... leave. It was a level of freedom that had never existed in human history, and it absolutely terrified the older generation.

How to see this history for yourself

If you want to actually understand cars 100 years ago, you shouldn't just look at photos. You need to see them in person because the scale is surprising. They are often much taller and narrower than you’d expect.

- The Henry Ford Museum (Dearborn, Michigan): This is the mecca. They have the "Automobiles in American Life" exhibit which shows the evolution of the 1920s landscape better than anywhere else.

- The Petersen Automotive Museum (Los Angeles): They often have "Vault" tours where you can see the high-end stuff from 1926, like the aforementioned Duesenbergs or early Packards.

- Local "Cars and Coffee" events: Look for Pre-War (referring to WWII) sections. Talk to the owners. Most people who own a 1926 Dodge or Buick are dying to tell you about the weird quirks of the vacuum-fed fuel systems.

What we can learn from 1926

Looking back, 1926 teaches us that technology doesn't move in a straight line. It moves in fits and starts. We are actually in a very similar spot right now with the shift to Electric Vehicles (EVs). Just like the internal combustion engine was fighting for dominance over steam and electric power in the early 20th century, we are seeing a massive infrastructure shift today.

The people in 1926 were dealing with "range anxiety" too—except their anxiety was about whether the next general store actually had a drum of gasoline in the back.

Moving forward: Your historical checklist

If you're researching this era or looking to buy a vintage project, keep these actionable points in mind:

Check the wood. Most cars in 1926 still used structural wood (often ash) inside the steel body panels. If that wood rots, the car loses its structural integrity, even if the metal looks fine.

Understand the electricals. 6-volt systems were the standard back then, not the 12-volt systems we use now. The lights are dim, and the starters are sluggish. It’s part of the charm, but it requires different maintenance.

Respect the babbitt bearings. Older engines didn't have the "insert" bearings we use today. They used poured babbitt metal. If you run a 1926 engine out of oil for even a second, you aren't just replacing a part—you're doing a specialized machining job that costs thousands.

Look at the tires. If you're looking at a survivor car, check if it has "split rims." These are notoriously dangerous to work on if you don't know what you're doing.

The world of 100 years ago wasn't just a slower version of our own. It was a louder, vibrantly experimental time where the rules of the road were being written in real-time. Next time you're sitting in traffic with your climate control and your smartphone, remember that in 1926, just getting to the next town without a flat tire or a broken arm was considered a successful afternoon.