Everything you see when you look in the mirror—and everything you don’t see, like the air you're breathing or the DNA zipping around your cells—basically exists because of a single digit. Four. That is the magic number. Specifically, it’s the number of valence electrons of carbon.

If carbon had three valence electrons, you wouldn't be here. If it had five, the universe would look like a giant, frozen rock pile. Because it has exactly four, carbon acts like the ultimate LEGO brick of the cosmos. It's the "Goldilocks" element. It’s not too reactive, like sodium, which explodes if it touches water. It’s not too snobbish, like neon, which refuses to talk to anyone. Carbon is the social butterfly of the periodic table. It wants to bond, and it wants to bond with almost everyone.

The "Four-Handed" Monster of Chemistry

Most people remember high school chemistry as a blur of beige posters and "S" and "P" orbitals. But let's strip the jargon away. Think of valence electrons of carbon as hands. Carbon has four hands. Most other elements have one, two, or maybe three. Oxygen has two. Hydrogen has one.

Because carbon has four hands, it can hold onto four different things at once. Or, it can use two hands to grip one friend really tightly (a double bond) and use its remaining two hands to grab someone else. It can even use three hands for a triple bond. This flexibility is what chemists call "tetravalency." It’s the reason we have millions of different organic compounds but only a handful of inorganic ones.

Where do these four actually live?

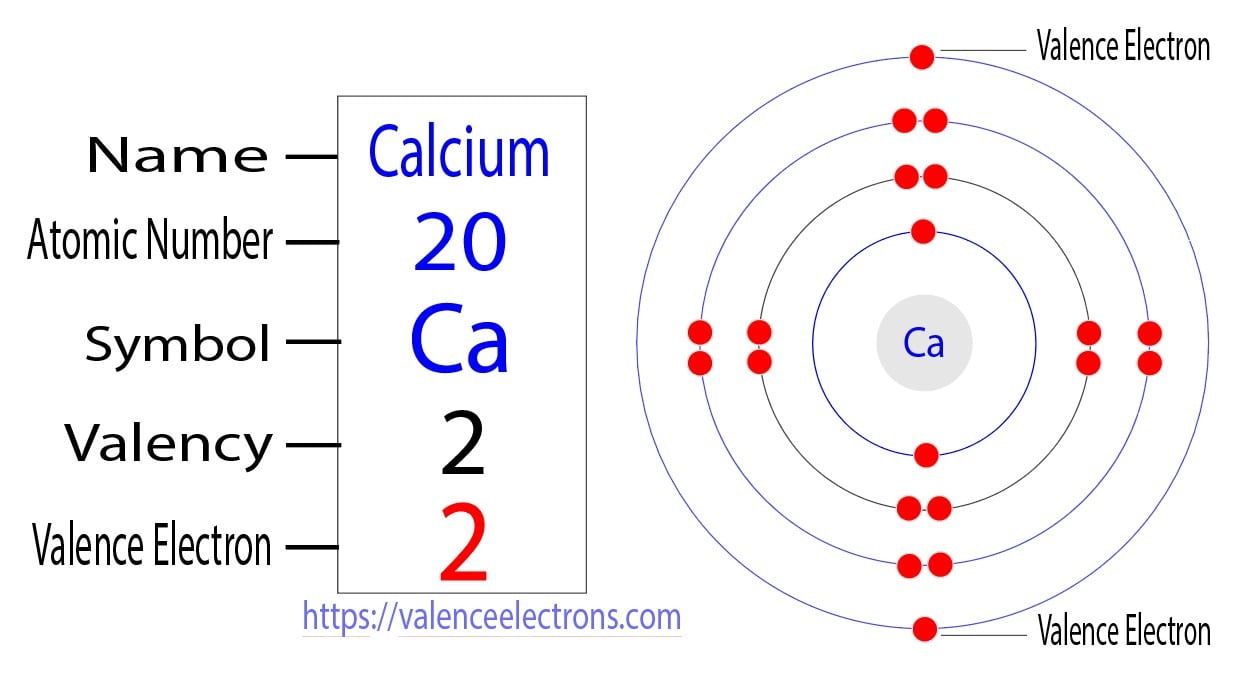

If we’re getting technical—and we should, because the details are cool—carbon is element number six. That means it has six protons and six electrons. Two of those electrons are tucked away in the inner "1s" shell. They’re homebodies. They don't do anything. The other four? They live in the outer shell. These are the valence electrons of carbon.

In their ground state, these four electrons are a bit awkward. They sit in the 2s and 2p orbitals. But when carbon gets ready to bond, it does something called hybridization. It’s like a transformer shifting gears. It promotes one electron from the 2s orbital up to the 2p orbital, creating four equal "sp3" hybrid orbitals. This isn't just a math trick; it’s a physical reality that gives carbon its signature tetrahedral shape.

Why 109.5 Degrees is the Most Important Angle in Your Body

When carbon uses its four valence electrons to bond with four hydrogens (forming methane, $CH_4$), those electrons want to stay as far away from each other as possible because they’re all negatively charged. Like charges repel. They push away until they settle into a perfect tetrahedron.

The angle between those bonds is exactly 109.5 degrees.

This 3D shape is why you aren't a flat piece of paper. It allows carbon to build rings, chains, branches, and complex 3D structures like proteins and enzymes. Without that specific tetrahedral geometry dictated by the valence electrons of carbon, your DNA wouldn't be a double helix. It would just be a useless clump of atoms.

The Diamond vs. Pencil Lead Paradox

It’s wild to think that the same four electrons create both the hardest material on Earth and the stuff that rubs off on your paper when you write.

- Diamonds: In a diamond, every single one of those four valence electrons is locked in a tight, covalent embrace with another carbon atom. It’s a rigid, 3D lattice. No loose electrons. No wiggle room. That’s why it’s so hard.

- Graphite: In your pencil lead, carbon only uses three of its valence electrons to bond in flat sheets. The fourth electron? It’s just hanging out, delocalized, sliding around between the layers. This makes the layers slippery. It also—interestingly enough—makes graphite a conductor of electricity, whereas diamond is an insulator.

Same element. Same number of valence electrons. Totally different vibes. It all comes down to how those four electrons choose to spend their Friday night.

💡 You might also like: Secondary Air Check Valve Failures: Why Your Engine Light Is Actually Screaming

The Octet Rule: Carbon’s Obsession with Eight

Nature loves symmetry and stability. For atoms in the second row of the periodic table, stability means having eight electrons in the outer shell. Since carbon only has four, it’s constantly on a quest for four more. It’s "half-full."

This "half-full" status is the secret sauce. If carbon had one valence electron (like Lithium), it would just give it away and become a boring ion. If it had seven (like Chlorine), it would aggressively steal one and call it a day. But because carbon is right in the middle, it doesn't steal and it doesn't give away. It shares.

Covalent bonding is the hallmark of the valence electrons of carbon. Sharing is much stronger than stealing. It creates stable, long-lasting bonds that can withstand the heat of a volcanic vent or the acidic environment of your stomach.

What about Silicon?

You’ll often hear sci-fi nerds talk about "silicon-based life." Silicon is right below carbon on the periodic table. It also has four valence electrons. So why aren't we made of sand?

Honestly, silicon is just too big. Its valence electrons are further from the nucleus, shielded by more inner shells. This makes silicon's bonds weaker. It can’t form the long, stable chains (catenation) that carbon handles with ease. While carbon can make a chain of 100 atoms without breaking a sweat, silicon starts to fall apart after just a few. Carbon is the elite athlete of the chemical world; silicon is the cousin who gets winded walking up the stairs.

How Carbon Electrons Power the Modern World

We aren't just talking about biology here. The valence electrons of carbon are the backbone of the energy industry.

When you burn gasoline or coal, you’re basically breaking the bonds between carbon and hydrogen (or other carbons). Those electrons are moving to a lower energy state by bonding with oxygen. That "drop" in energy level is released as heat and light. Every mile you drive is powered by the rearrangement of carbon’s four outer electrons.

Even in the tech world, we’re looking at Graphene. Graphene is a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal honeycomb. Because of how the valence electrons of carbon behave in this specific 2D arrangement, electrons can fly through graphene at speeds approaching the speed of light. It’s being touted as the successor to silicon in our computer chips.

Common Misconceptions About Carbon Bonds

I’ve seen a lot of "pop science" articles get this wrong. People think carbon must always have four bonds. Not quite.

- Carbon Monoxide (CO): Here, carbon is in a weird spot. It shares three pairs of electrons with oxygen.

- Carbenes: These are highly reactive species where carbon only has two bonds and two unshared electrons. They don't last long, but they are crucial in chemical manufacturing.

- Radicals: Sometimes carbon ends up with an unpaired electron. These "free radicals" are what antioxidants in your blueberries are trying to neutralize.

But for 99% of the stuff that matters—your skin, your food, your fuel—it’s all about those four stable bonds.

Taking Action: How to Use This Knowledge

If you’re a student, an engineer, or just someone who likes knowing how the world works, understanding the valence electrons of carbon is your "Level 1" key.

- For Chemistry Students: Stop memorizing formulas. Start looking at the geometry. If you can visualize where those four electrons are trying to go, organic chemistry becomes a game of spatial reasoning rather than rote memorization.

- For Health Enthusiasts: When you hear about "saturated" vs. "unsaturated" fats, look at the carbon. Saturated fats have carbons that are "full"—using all their valence electrons to hold single hydrogens. Unsaturated fats have double bonds (carbon using two hands for one neighbor), which creates a "kink" in the chain. That kink is why olive oil is liquid and butter is solid.

- For the Curious: Next time you look at a piece of plastic (a polymer), realize it’s just a massive, repeating chain of carbon atoms using their valence electrons to hold onto each other like a never-ending game of Red Rover.

The universe is built on a very simple foundation. Carbon’s four valence electrons provide the perfect balance of strength, flexibility, and sociability. It’s the ultimate architectural tool, and we are the living proof of its success.

📖 Related: Converting 25 degrees celsius to k: Why this specific number rules the lab

To really grasp this, your next step should be looking into molecular modeling software (like ChemDraw or even free web-based versions). Try building a simple glucose molecule. You'll see immediately how those four valence electrons force the molecule into a specific, life-sustaining shape that a 2D drawing can never capture.