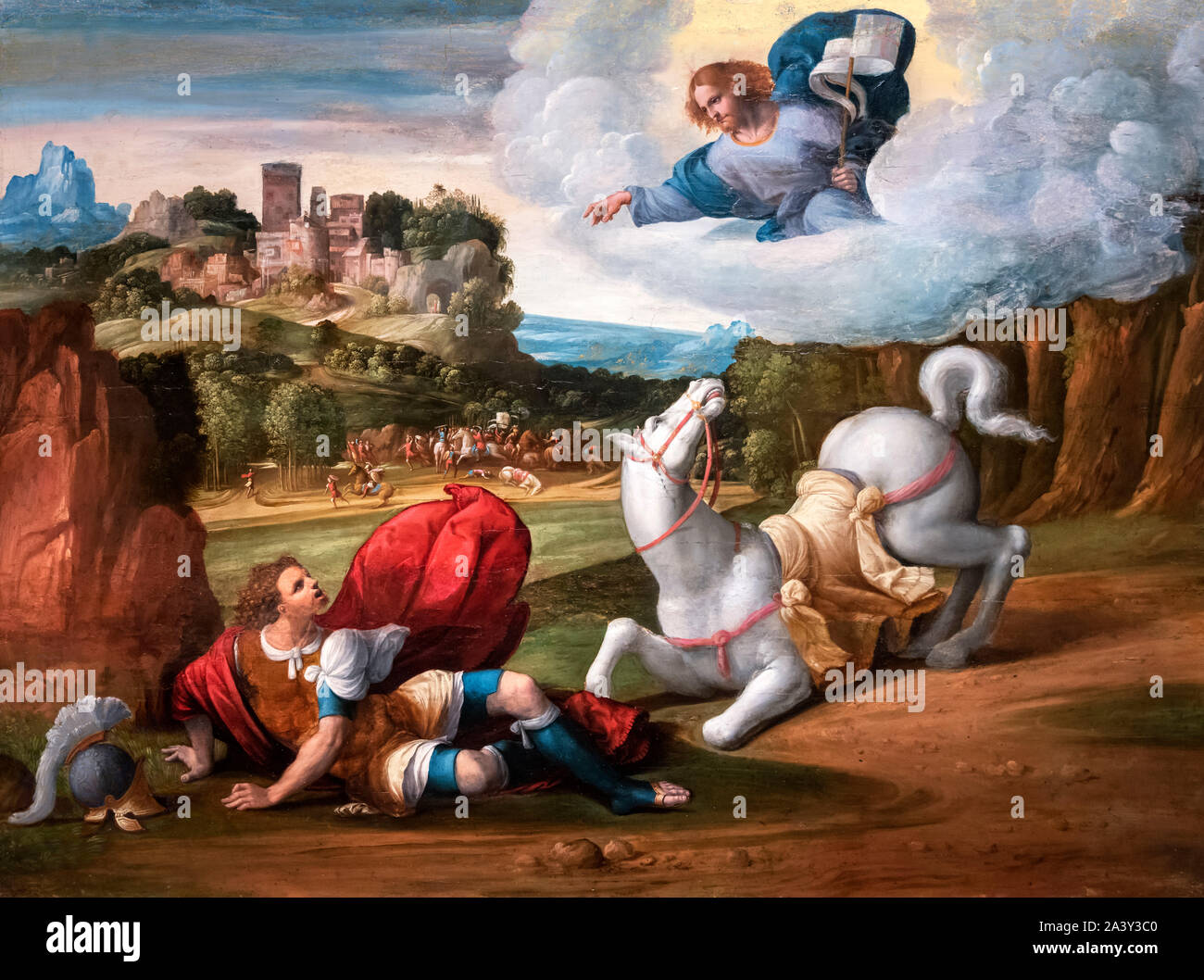

If you walked into the Cerasi Chapel in Rome today, you’d probably be a bit confused. You are looking for a masterpiece. You expect a grand, celestial vision of a saint bathed in light, surrounded by fluttering angels and perhaps a divine choir. Instead, you get a horse’s backside. Honestly, it’s the first thing you notice about Caravaggio’s conversion of st paul painting.

It is massive. It is hairy. It is incredibly mundane.

This isn't the version of the story most people grew up with in Sunday school. There is no Jesus floating in the clouds. There aren’t even any roads. There is just a man on the ground, a giant horse, and a very tired-looking groom. It’s gritty. It’s dark. It’s also arguably the most influential piece of Baroque art ever created.

The 1601 Controversy: What Caravaggio Actually Did

Caravaggio was a bit of a nightmare to work with. He was a brawler, a fugitive, and a genius who didn't care much for tradition. When he was commissioned to paint the Conversion on the Way to Damascus for the Santa Maria del Popolo, he actually turned in two versions. The first one was rejected. Why? Because it was too chaotic.

But the second version—the one we see today—is the one that really flipped the art world upside down.

In the late Renaissance, "holy" meant "perfect." Saints were supposed to look like statues. Caravaggio said no to all that. He used a technique called tenebrism. It’s basically like a spotlight in a dark room. Everything is pitch black except for the most intense, violent highlights. In the conversion of st paul painting, this light isn't coming from a window or a candle. It’s the light of God. But instead of showing God, Caravaggio just shows what the light does to the people it hits.

It makes Saul (who becomes Paul) look vulnerable. He’s flat on his back. His arms are spread wide. He looks like he just fell off a bike, not like he’s receiving a divine revelation.

The Horse Problem

Let's talk about that horse again. Critics at the time were legitimately angry about it. There’s an old story—maybe apocryphal, but it fits the vibe—where a church official asked Caravaggio why he put a horse in the middle of the scene and God nowhere.

🔗 Read more: Pink White Nail Studio Secrets and Why Your Manicure Isn't Lasting

Caravaggio reportedly replied, "The horse is standing in God's light."

The horse is a Piebald. It’s mottled and realistic. If you look closely at the hoof, it’s hovering just inches above Paul’s body. There is a tension there. Is the horse going to crush him? Is it protecting him? It adds a layer of physical danger to a spiritual moment. Most artists before Caravaggio focused on the "spirit" part. He focused on the "falling off a horse and hitting the dirt" part.

Why the Conversion of St Paul Painting Still Hits Different

When you look at other versions of this scene—like Michelangelo’s—there are people everywhere. It’s a crowd scene. It’s loud. Caravaggio’s version is silent.

It’s just three figures:

- Paul: Lying on the ground, eyes closed, seemingly in a trance.

- The Horse: Calmly being led by the groom.

- The Groom: An old man with wrinkled skin who looks like he just wants to get back to the stable.

This choice is brilliant. It suggests that a religious experience isn't a public event. It’s internal. The groom has no idea what’s happening. To him, it’s just a Tuesday and his boss just fell down. This contrast between the mundane world and the supernatural event is what makes the conversion of st paul painting feel so modern.

It’s a psychological portrait.

The Technical Wizardry of Tenebrism

Caravaggio didn't use sketches. Most experts, like Andrew Graham-Dixon, note that Caravaggio painted directly onto the canvas. He’d score the wet primer with the end of his brush to mark where the limbs went.

💡 You might also like: Hairstyles for women over 50 with round faces: What your stylist isn't telling you

In the conversion of st paul painting, the composition is a mess of diagonals. Follow the line of Paul’s arms. Then the horse’s leg. Then the groom’s back. It’s a "X" shape that keeps your eyes circling the center of the canvas. You can't look away.

The color palette is restricted too. Earthy browns, ochre, and that shocking red of Paul’s cloak. That red is vital. It’s the color of blood, the color of the office of the Pharisee that Paul is about to leave behind. It’s the only "loud" color in the whole room.

Myths vs. Reality

People often say Paul was a Roman soldier. He wasn't. He was a Pharisee, a religious leader. Caravaggio dresses him in a sort of Roman-esque leather cuirass, but that’s more about the style of the 1600s than historical accuracy.

Another big misconception? That the Bible says he fell off a horse.

Actually, the Book of Acts never mentions a horse. It just says he "fell to the ground." But by 1600, the horse had become a symbol of pride. By putting Paul under the horse, Caravaggio is literally showing pride being stepped on. It’s a visual metaphor that everyone in Rome would have understood instantly.

How to See It Without the Crowds

If you want to see the conversion of st paul painting in person, you have to go to the Piazza del Popolo. The church is free. That’s the good news.

The bad news is the lighting.

📖 Related: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

The chapel is dark. To see the painting properly, you have to put a coin (usually a Euro or two) into a little machine that turns the lights on for about 60 seconds. It’s a bit of a hustle, honestly. But there is something magical about that light clicking on and seeing Paul’s outstretched arms emerge from the shadows.

What to Look for specifically:

- The Veins: Look at the groom's legs. Caravaggio painted the varicose veins. It’s that level of "ugly" realism that made people call him a "sociopath with a paintbrush."

- The Eyes: Paul’s eyes aren't just closed; they are squeezed shut. He’s blinded by the light.

- The Space: Notice how Paul’s hands seem to reach out into your space. It’s 3D before 3D existed.

Actionable Insights for Art Lovers

If you're studying the conversion of st paul painting for a class, or just because you like cool stuff, don't just look at it as a "religious painting." Look at it as a study in human vulnerability.

Research the "First Version": Caravaggio’s first attempt at this painting is now in the Odescalchi Balbi Collection in Rome. It’s totally different. Seeing the two side-by-side (digitally, since the first is private) shows you how an artist edits their own "brand."

Visit the Sister Painting: Directly across from the Paul painting is the Crucifixion of St. Peter. Caravaggio painted them as a pair. One man is being called to life; the other is being called to death.

Understand the Counter-Reformation: This painting wasn't just "art." It was propaganda. The Catholic Church wanted art that made people feel something powerful to keep them from turning Protestant. Caravaggio’s raw, dirty, "street-level" holiness was exactly what they needed, even if it scared them.

The best way to appreciate this work is to ignore the "fine art" label for a second. Imagine you are Paul. You are successful, you are powerful, and then suddenly, the world flips. You are on your back in the dirt, and the only thing between you and a heavy hoof is a bit of luck and a lot of grace. That is what Caravaggio was trying to capture. It’s not about the saint; it’s about the moment everything changed.

To truly understand the impact of this work, compare it to the High Renaissance works of Raphael. Where Raphael sought balance and harmony, Caravaggio sought tension and grit. Seeing these two styles in the same city—often just blocks apart—is the best crash course in how Western thought shifted from the ideal to the real.