Walking into Eastern State Penitentiary feels like stepping into a giant, crumbling lung. It’s heavy. The air is thick with the scent of wet stone, peeling lead paint, and a century of forced silence. If you’ve ever scrolled through eastern state penitentiary pictures online, you probably felt that weird mix of discomfort and curiosity. Those images aren't just "ruin porn." They’re a visual record of a massive, failed social experiment. Honestly, it’s one thing to see a photo of a rusted bed frame in a cell, but it’s another thing entirely to realize that specific bed was someone’s whole world for fifteen years.

Philadelphia is full of history, sure. You’ve got the Liberty Bell and the tacky cheesesteak spots. But this place? It’s different. It was the world’s first true "penitentiary"—a place designed to make people feel penance. No talking. No seeing other inmates. Just you, a Bible, and the "Eye of God" skylight. When you’re trying to photograph that, you aren’t just looking for a cool shot; you’re trying to capture the weight of total isolation.

The Architecture of Absolute Silence

Most people don't realize that Eastern State was the most expensive public structure in the United States when it was built in 1829. The architect, John Haviland, went with a radial design. Think of a wagon wheel. The hub in the middle allowed a single guard to look down all seven cell blocks at once. It’s terrifyingly efficient.

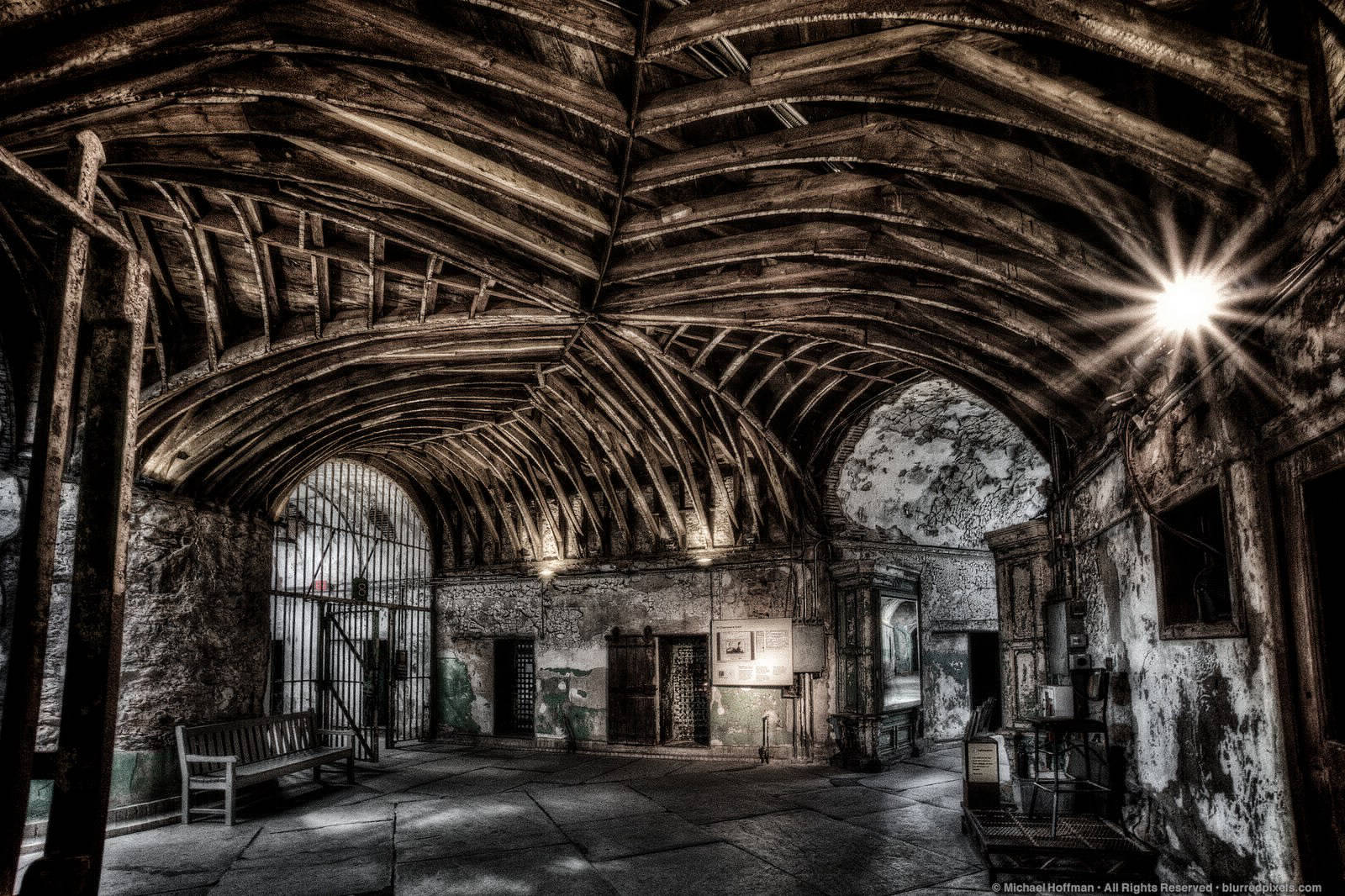

When you're looking for the best eastern state penitentiary pictures, you usually see that iconic shot from the center of the surveillance hub. It’s the money shot for a reason. From that one spot, you can see the long, vaulted corridors stretching out like skeletal fingers. The ceilings are high, pointed, and church-like. That was intentional. Haviland wanted prisoners to feel like they were in a monastery. He wanted them to look up.

But the reality was grimmer than the architecture suggests. The walls were thick—thick enough to prevent any tapping or communication between cells. Early on, inmates wore hoods when they were moved so they wouldn’t even know what their neighbors looked like. Imagine trying to photograph that kind of loneliness. Photographers today often focus on the textures: the way the plaster curls off the walls like dried skin or how the sunlight hits the dust motes in a way that feels almost holy, despite the misery that happened there.

Cellblock 12 and the Gothic Aesthetic

If you want the really "haunted" look, Cellblock 12 is where it’s at. It’s a three-story block, which was a departure from the original plan, and it feels much more oppressive. The stairs are narrow. The shadows are longer.

A lot of the "ruin photography" movement actually owes a debt to this building. In the late 90s and early 2000s, after the prison had sat abandoned for decades, it became a pilgrimage site for people with DSLRs. They were looking for that perfect contrast between the industrial grit and the soft, natural light coming through the skylights. These skylights were nicknamed "Dead Lights." Not exactly a cheery vibe, right?

🔗 Read more: Entry Into Dominican Republic: What Most People Get Wrong

Al Capone’s Cell: The Big Exception

You can’t talk about eastern state penitentiary pictures without mentioning "Scarface." Al Capone spent about nine months here in 1929 and 1930. But his cell wasn't like the others. While everyone else was rotting in cold, damp boxes, Capone had oriental rugs, fine furniture, and a radio.

It’s honestly jarring to see. You’re walking past rows of crumbling, grey cells, and then suddenly—BAM. You’re looking at a room that looks like a smoky 1920s study. It’s one of the few restored areas in the prison. Taking photos here is tricky because of the glass partition, but it serves as a massive middle finger to the "silent system" the prison was supposed to uphold. It shows that even in a place designed for absolute equality in suffering, money still talked.

The Contrast of Modern Art

One thing that surprises people visiting today is the art. The penitentiary isn't just a stagnant museum; they bring in contemporary artists to create installations in the cells.

- There’s "Ghost Cats," which is a series of sculptures commemorating the stray cats that lived in the ruins after it closed in 1971.

- You’ve got "The Big Graph," a massive 16-foot-tall steel sculpture in the courtyard that shows the soaring rates of incarceration in the US.

- Some artists use soundscapes to recreate the "noises" of the prison, which makes the visual experience way more intense.

This creates a weird, beautiful layering in photos. You might see a 19th-century cell door with a 21st-century neon light installation inside it. It’s a reminder that the building's story didn't end when the last prisoner left.

Why the "Decay" Looks So Good on Camera

There is a technical reason why eastern state penitentiary pictures always look so professional, even if you’re just using a phone. It’s the "stabilized ruin" philosophy. The people who run the site don’t "fix" the walls. They don’t repaint things to look new. They just stop the building from falling down further.

This means you get incredible "chiaroscuro"—the dramatic interplay of light and dark. Because the windows are mostly skylights, the light comes from directly above. It creates these long, vertical columns of brightness that cut through the gloom. If you go on a rainy day, the stone turns dark and moody. If you go on a bright afternoon, the peeling paint creates shadows that look like topographical maps.

💡 You might also like: Novotel Perth Adelaide Terrace: What Most People Get Wrong

Tips for the Amateur Photographer

Honestly, if you're going there to take photos, don't just bring a wide-angle lens. Everyone gets the long hallway shot. Try to get close.

- Focus on the hardware. The locks on these doors are massive. They’re heavy, rusted, and look like something out of a medieval dungeon.

- Look for the greenery. There are spots where nature is literally eating the building. Trees growing through the roof, moss on the floors. It’s that "Life After People" vibe.

- Check the corners. Some of the best shots are the ones that show the plumbing. Eastern State actually had flush toilets and central heating before the White House did. Seeing those rusted pipes against the stone walls tells a huge story about the "luxury" of the prison’s early days.

The Ethical Dilemma of the Lens

We have to talk about the "dark tourism" aspect of this. It’s easy to get caught up in the aesthetics of a crumbling building. It’s beautiful in a tragic way. But these were real cells.

When you're looking at or taking eastern state penitentiary pictures, it’s worth remembering that this place was a site of immense mental suffering. The "Philadelphia System" (the silent system) drove people insane. The lack of human contact wasn't a side effect; it was the point.

Historians like those at the Smithsonian have pointed out that while the prison was meant to be "humane" compared to the public hangings and floggings of the past, the psychological toll was arguably worse. Charles Dickens visited in 1842 and was absolutely horrified. He called it "rigid, strict, and hopeless." You can see that hopelessness in the scratches on the walls or the way the floors are worn down in specific patterns from men pacing in small circles.

How to Get the Best Shots Today

If you're planning a trip to get your own eastern state penitentiary pictures, timing is everything.

The "Golden Hour" isn't really a thing inside a stone fortress, but the "Winter Light" is. In the late fall and winter, the sun sits lower in the sky. This means the light hits the vertical windows in the cellblocks at a sharper angle, creating longer, more dramatic shadows.

📖 Related: Magnolia Fort Worth Texas: Why This Street Still Defines the Near Southside

Also, they do "Night Tours" occasionally. If you can snag a ticket for those, the artificial lighting they use is incredibly cinematic. It highlights the textures of the stone in a way that sunlight can't. It’s creepy as hell, but the photos are unmatched.

A Note on Equipment

Don't overthink it. You don't need a $5,000 rig.

- Tripods: They aren't usually allowed during standard tours because the walkways are narrow and it’s a tripping hazard.

- Lenses: A fast prime lens (like a 35mm f/1.8) is great for the low light inside the cells.

- Phones: Modern iPhones and Pixels do a great job with the HDR needed to balance the bright skylights with the dark corners.

The Legacy of the Image

Ultimately, why do we keep looking at these images? Why is "Eastern State Penitentiary pictures" a search term that never dies?

Maybe it’s because the building is a mirror. It shows us what we thought was the "right" way to treat people 200 years ago, and it forces us to look at how we treat people now. The decay isn't just physical; it's a metaphor for an outdated philosophy.

The site is a National Historic Landmark now, and it’s one of the most visited spots in Philly. It’s not a "fun" visit, but it’s a necessary one. Whether you’re there for the history, the ghost stories (of which there are many, mostly unverified but fun for the "Terror Behind the Walls" event), or the photography, the place stays with you.

Practical Next Steps for Your Visit

If you're ready to see it for yourself, here is how you should handle it:

- Book in advance: It’s 2026, and the site is more popular than ever. Don’t just show up and expect to walk in.

- Wear layers: Even if it’s 90 degrees outside, the stone walls keep the interior surprisingly chilly. Plus, it’s damp.

- Listen to the audio tour: It’s narrated by Steve Buscemi (yes, really), and it’s one of the best museum tours in the country. It gives context to the things you’re photographing so your captions can actually be accurate.

- Check the Art Calendar: See which installations are currently active. Some of them are temporary and provide a once-in-a-lifetime photo op that won't be there next year.

Taking photos here is about more than just a cool Instagram post. It’s about documenting a piece of American history that was almost bulldozed to make way for a shopping mall. We’re lucky it’s still standing, even if it is falling apart.