You’re walking through a clean, quiet neighborhood in Tokyo, maybe grabbing a coffee at a 7-Eleven, and you probably don't realize that just a few miles away, someone might be waiting to die. It’s a weird contrast. Japan is this ultra-modern, polite, and incredibly safe society, yet it remains one of the very few developed democracies—alongside the U.S.—that still executes people. But the way they do it? It’s nothing like the American system. It is secretive, rigid, and, frankly, pretty chilling when you dig into the mechanics of it.

Japan doesn't use lethal injection. They don't use the electric chair. They use the long-drop hanging method.

The Secretive Nature of the Death House

The first thing you have to understand about capital punishment in Japan is the silence. In the United States, execution dates are set months in advance. There are appeals, media frenzies, and final meals that get reported in the news. In Japan, it’s the opposite. An inmate on death row wakes up every single morning not knowing if it’s their last day on earth.

They aren't told.

The guards just show up in the morning, usually around 8:00 or 9:00 AM, and tell the prisoner their time is up. They have maybe an hour or two to say a prayer, have a final snack, and write a letter. Their family? They find out after the body has already been taken down. Their lawyers? They get a phone call once the trapdoor has already clicked shut. It’s a policy designed to prevent "unrest" and keep the system moving without public interference.

Human rights groups like Amnesty International and the Japan Federation of Bar Associations (JFBA) have screamed about this for decades. They call it psychological torture. Imagine living 15 years in a cell, waking up every day at dawn, listening for the sound of boots in the hallway, wondering if today is the day. That is the reality for the roughly 100 people currently sitting in Japanese detention centers.

The Case of Iwao Hakamada: A Warning Tale

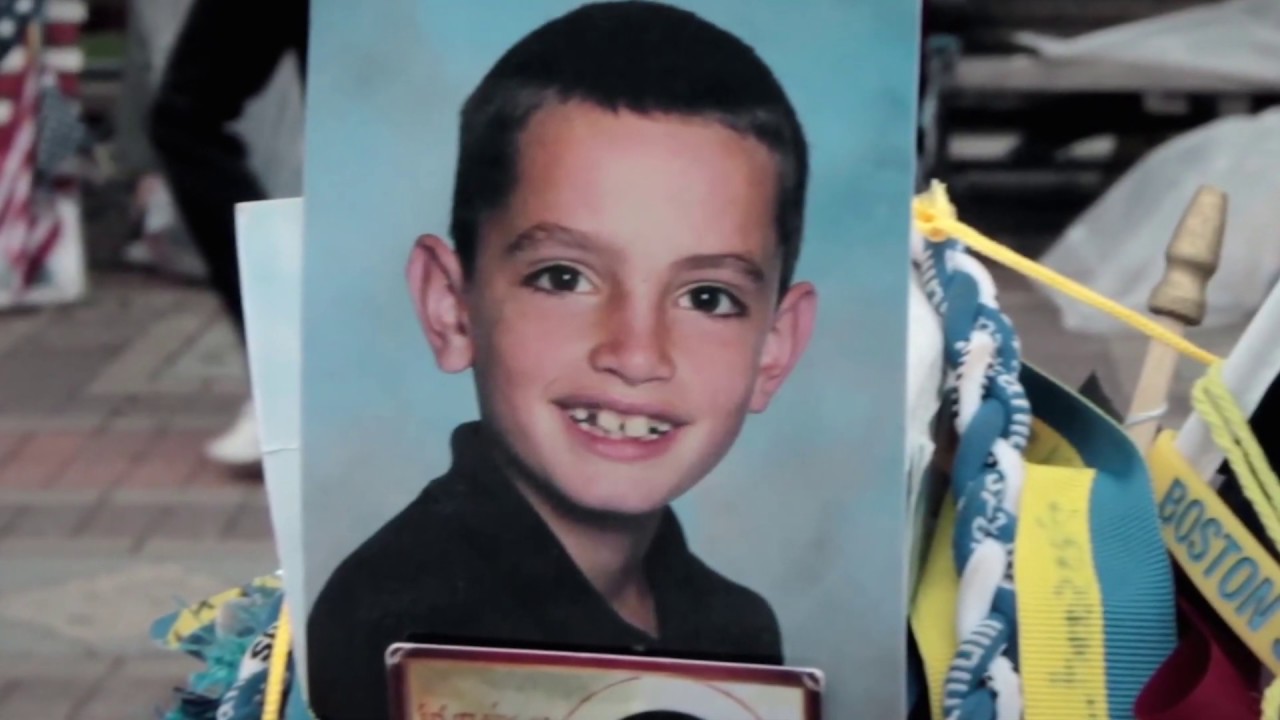

You can't talk about the death penalty in Japan without talking about Iwao Hakamada. His story is basically a nightmare fueled by a legal system that relies way too much on confessions. Hakamada was a professional boxer who was accused of killing his boss and the boss’s family back in 1966. He "confessed" after 20 days of brutal interrogation—we're talking 12 hours a day without a lawyer.

✨ Don't miss: Ukraine War Map May 2025: Why the Frontlines Aren't Moving Like You Think

He spent 46 years on death row.

Think about that. Nearly half a century in a tiny cell, mostly in solitary confinement. It wasn't until 2014 that DNA evidence basically proved the blood on the clothes used to convict him wasn't his. He was finally acquitted in a retrial in September 2024. He’s now an old man, his mind largely broken by the decades of isolation. Hakamada is the poster child for why critics say the Japanese "Lay Judge" system—where regular citizens sit alongside professional judges—needs to be way more skeptical of police "confessions."

Why Does the Public Support It?

If you ask the average person in Osaka or Fukuoka what they think, they’ll probably tell you they support capital punishment in Japan. It’s consistently polling at around 80% support. People see it as a "life for a life" thing. There's a deep-seated cultural belief in retribution over rehabilitation for the most heinous crimes.

In Japan, you generally don't get the death penalty for a single murder unless there are "aggravating factors" like rape or robbery. The "Nagayama Criteria"—named after a 19th-century killer—is the unofficial rulebook judges use. Basically, if you kill two or more people, you're almost certainly going to the gallows. If you kill one, you might get life.

It's about social order.

The government argues that the death penalty deters violent crime. Does it? Japan’s murder rate is incredibly low, but sociologists often argue that’s more about the culture, the strict gun laws, and the poverty rate rather than the fear of the rope. Still, the Ministry of Justice isn't budging. They view the death penalty as a cornerstone of public safety.

🔗 Read more: Percentage of Women That Voted for Trump: What Really Happened

The Hanging Process: A Stark Reality

When the order is signed by the Minister of Justice—a move that is often political and happens in "batches"—the execution takes place in one of seven detention centers (Tokyo, Osaka, Nagoya, etc.).

The room is divided. There’s a glass partition. The prisoner is blindfolded and handcuffed. The noose is a thick, high-quality hemp rope. The unique part is the "three-button" system. Three different guards each press a button simultaneously in a separate room. Only one of those buttons actually triggers the trapdoor, but none of the guards know which one. This is meant to spread the psychological "burden" of the killing.

It’s efficient. It’s clinical. And it’s very, very fast.

The Changing Tide or Business as Usual?

Lately, things have felt a bit different. The JFBA is getting louder, calling for an outright abolition by 2030. They point to the risk of "irreversible" mistakes, like the Hakamada case. Also, Japan is feeling the heat internationally. The European Union regularly puts pressure on Japan to stop, arguing that it's a "cruel and unusual" practice that doesn't belong in a modern state.

But honestly? Don't expect a change tomorrow. The ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) knows it has the public's backing. Even when the more "liberal" Democratic Party of Japan was in power briefly around 2010, they only paused executions for a short while before starting them up again.

The secrecy keeps the debate quiet. Because the public doesn't see the execution, and the media isn't allowed to film the facilities, the "reality" of the death penalty stays hidden. It’s an abstract concept for most Japanese citizens, not a grisly news story.

💡 You might also like: What Category Was Harvey? The Surprising Truth Behind the Number

What This Means for Global Justice

Japan’s stance creates a weird friction in international law. It’s a country that prides itself on being a leader in human rights in Asia, yet it maintains a practice that much of the world has abandoned. This creates a "dual-track" identity. On one hand, you have the high-tech, peaceful Japan of G7 summits; on the other, you have the medieval-style hanging rooms in the basements of urban detention centers.

If you’re following this topic, you’ve gotta watch the Ministry of Justice’s annual reports. They are sparse, but they tell you everything. They list the names and the crimes, but never the date until after it's done.

Actionable Insights for Researching Capital Punishment

If you want to understand the reality of this system better, you can't just look at government press releases. You have to look at the work of people who have actually been inside.

- Study the Nagayama Criteria: If you're a legal buff, look up how judges weigh "cruelty" versus "remorse." This is the secret sauce of Japanese sentencing.

- Follow the JFBA (Japan Federation of Bar Associations): They are the most credible source for data on "forced confessions" (Shukon) and how they lead to wrongful death sentences.

- Look at the "Batch" Timing: Notice when executions happen. They often occur during holidays or when the news cycle is busy with something else—this is a deliberate strategy to minimize social protest.

- Compare the "Life Without Parole" Gap: One reason support for the death penalty is so high in Japan is because "Life with Parole" often means the person could be out in 20-30 years. Japan doesn't have a true "Life Without Parole" (LWOP) sentence in the way the U.S. does. Implementing LWOP might be the only way to lower public support for executions.

The system is designed to be invisible. But for the people living in those 5-square-meter cells, the silence of the Japanese death row is the loudest thing in the world. As Japan continues to navigate its role as a global moral leader, the trapdoor remains a very real, very dark part of the national identity.

Next Steps for Further Investigation:

- Examine Retrial Laws: Research why it is notoriously difficult to get a retrial in Japan (the "Iron Door" of the courts).

- Monitor the Hakamada Legacy: Track whether the 2024 acquittal leads to new legislation regarding the recording of police interrogations.

- Review International Pressure: Look for the next UN Human Rights Committee report on Japan to see how the government defends its "confidentiality" policies.