If you look at a Cape of Horn map, you’re basically staring at the graveyard of the Atlantic. It’s a jagged, cold, and honestly terrifying piece of geography that marks where the Atlantic and Pacific oceans decide to fight each other. Sailors used to call it "the end of the world," and even with GPS, modern charts, and satellite imagery, that feeling hasn't really gone away.

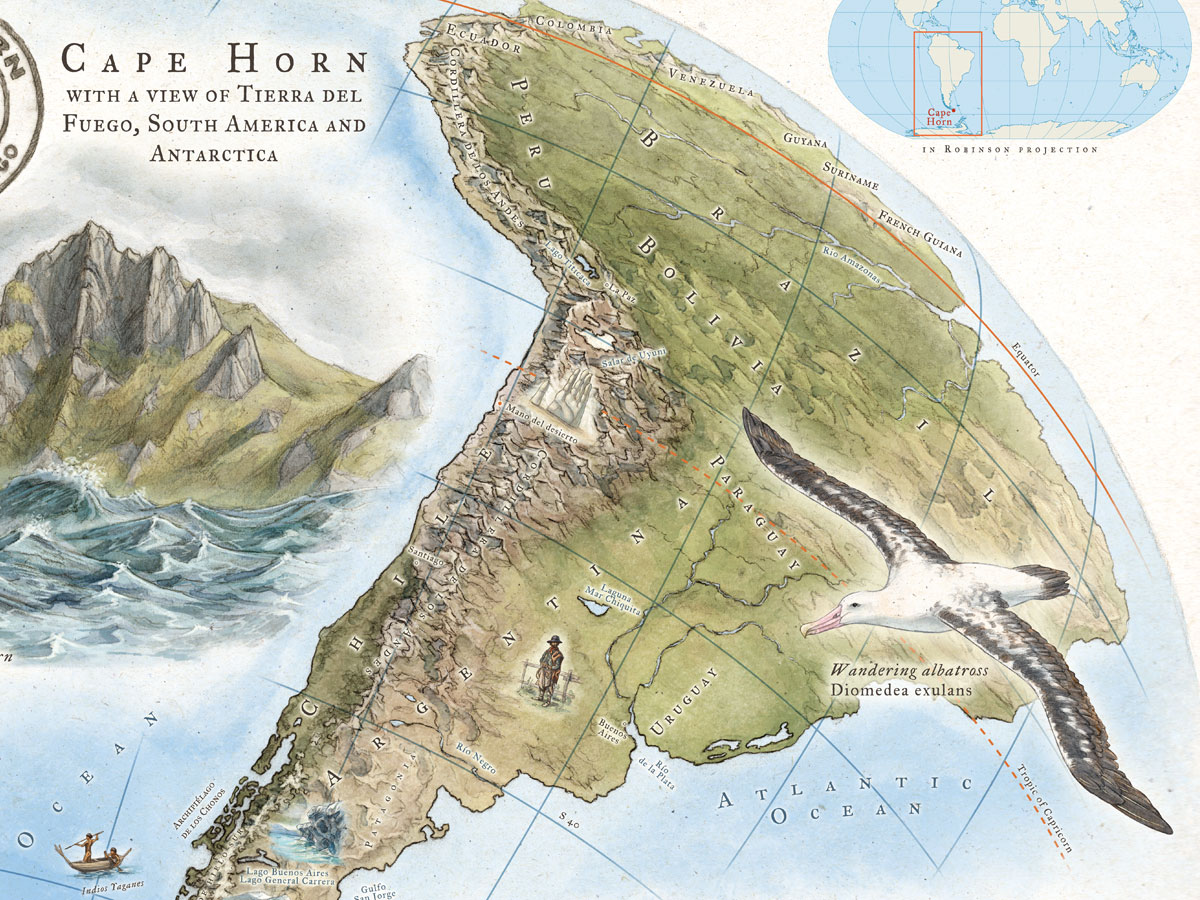

Most people think Cape Horn is just a point on a map. It’s actually the southernmost headland of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago in southern Chile. It’s located on Hornos Island.

The weather here is legendary for all the wrong reasons. Because there’s no significant landmass at that latitude to slow down the wind, the "Roaring Forties" and "Furious Fifties" just whip around the globe and slam into the Andes. This creates a funnel effect. You get massive waves—sometimes 60 to 100 feet tall—and currents that can strip the paint off a hull.

Reading the Cape of Horn map: More than just a point

When you zoom in on a Cape of Horn map, you notice it isn't the true southernmost point of South America. That honor actually belongs to the Diego Ramírez Islands, which sit about 60 miles further southwest. But Cape Horn is the symbolic one. It's the "Everest of Sailing."

The map shows a complex network of channels, bays, and tiny islands. To the north is the Beagle Channel, named after the ship that carried Charles Darwin. To the south, the Drake Passage. The Drake Passage is roughly 500 miles of open water between the Horn and the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica. It’s the shortest crossing to the white continent, but it’s rarely a smooth ride.

Why the geography is so weirdly dangerous

The continental shelf around the Horn is shallow. Imagine billions of tons of deep-ocean water moving at high speeds across the Pacific. Suddenly, that water hits a wall—the continental shelf near the Cape. The water has nowhere to go but up. This creates "rogue waves" and incredibly steep seas that can roll even the largest cargo ships.

📖 Related: Why San Luis Valley Colorado is the Weirdest, Most Beautiful Place You’ve Never Been

Most maps don't show the shipwrecks. If they did, the paper would be covered in ink. It’s estimated that over 800 ships and 10,000 sailors have been lost in these waters since the 16th century. Names like the Wager and the Sussex are etched into the maritime history of this specific coordinate.

Navigating the Drake Passage today

Even in 2026, technology only helps so much. You've got high-resolution bathymetric data now, which gives us a 3D view of the seafloor. This helps captains understand how those massive swells will behave. But you can't "tech" your way out of a 70-knot gale.

Modern sailors use specialized digital overlays on their Cape of Horn map software. These layers show real-time sea surface temperatures, wave height predictions from models like the Wavewatch III, and ice limits. Yes, icebergs are a real threat here, especially as chunks break off the Antarctic shelf and drift north into the shipping lanes.

The Albatross Monument

If you manage to land on Hornos Island—which is a big "if" depending on the swell—you'll see the Albatross Monument. It’s a massive steel silhouette of an albatross. The wind whistles through it, making a haunting sound. It commemorates the sailors who died trying to "round the Horn."

The Chilean Navy maintains a station here. There’s a lighthouse keeper and their family who live on this rock for a year at a time. They track every vessel that passes. They are the human element in an otherwise digital world of navigation.

👉 See also: Why Palacio da Anunciada is Lisbon's Most Underrated Luxury Escape

The technical reality of the "Cape Horn Climb"

Heading east to west is the hardest way to go. You're fighting the prevailing winds and the Antarctic Circumpolar Current. This is called "rounding the Horn the wrong way." In the days of sail, ships could spend weeks, or even months, trying to make headway against the gales.

- Wind speeds often exceed 100 km/h.

- Water temperature hovers around 5°C (41°F).

- Atmospheric pressure drops faster here than almost anywhere else on Earth.

Today, cruise ships and private yachts still make the journey. But they don't just "wing it." They use weather routing services that analyze satellite data to find "windows" of relatively calm weather. Even then, it’s a gamble. I’ve seen 400-foot expedition ships get tossed around like bathtub toys in the Drake.

Misconceptions about the Cape

People often confuse Cape Horn with the Strait of Magellan. The Strait is further north and cuts through the land. It’s safer, but it’s narrow and tricky to navigate. Cape Horn is the "open sea" route.

Another mistake? Thinking the water is always blue. In reality, the Cape of Horn map covers an area where the water is often a dark, bruised grey-green. The sky is rarely clear. It’s a landscape of shadows and spray.

The "Cape Horners" were a prestigious group of sailors who had successfully rounded the point. Traditionally, they earned the right to wear a gold hoop earring in their left ear and to dine with one foot on the table. It sounds like pirate lore, but it was a real mark of respect in a profession where death was a daily possibility.

✨ Don't miss: Super 8 Fort Myers Florida: What to Honestly Expect Before You Book

How to use a Cape of Horn map for your own trip

If you're planning to actually visit, don't just look at a static map. You need dynamic tools.

- Check the ice charts. The National Ice Center (NIC) provides regular updates on where the "growlers" (small, hull-crushing ice chunks) are drifting.

- Monitor the "Pacific High" and "Antarctic Low." The interaction between these two pressure systems dictates whether you'll have a smooth crossing or a nightmare.

- Understand the tides. While the open ocean doesn't care much about tides, the narrow channels around the Wollaston Islands (where the Horn is located) have fierce tidal rips.

The best time to visit is during the southern summer, from December to February. The sun barely sets, and the weather is... well, it's still bad, but it’s "less bad."

Why we still care about this coordinate

In a world where everything is mapped and tracked, Cape Horn remains one of the few places that feels untamed. It’s a bottleneck of global geography.

The Cape of Horn map is a reminder that nature doesn't care about our schedules or our technology. Whether you're a professional mariner or an armchair traveler, looking at that tiny point at the bottom of the world evokes a sense of awe. It represents the limit of human endurance.

To get the most out of your study of this region, stop looking at the land and start looking at the water depths. The transition from the 4,000-meter deep Pacific to the 100-meter deep shelf around the Horn tells the real story of why this place is so violent. It’s a physical collision of planetary forces.

Actionable Steps for the Modern Explorer

- Study the Bathymetry: Use tools like GEBCO (General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans) to see the underwater mountains that cause the Cape's famous waves.

- Track the Weather: Follow the "Windy" app or similar GFS/ECMWF model visualizations for the coordinates 55°58′48″S 067°17′21″W. It’s a crash course in meteorology.

- Read the Logs: Look up the "Golden Globe Race" archives. It’s a solo, non-stop round-the-world sailing race. The accounts of the skippers passing the Horn in 2022 and 2023 provide the best "boots on the ground" perspective of what the maps don't tell you.

- Respect the Distance: Remember that the nearest major city, Ushuaia, is still a significant journey away. If things go wrong at the Horn, you are very much on your own.

Understanding the Horn means accepting that a map is just a suggestion. The ocean has the final say.