You’re out in the Okavango Delta, the sun is just starting to bake the tall grass, and suddenly you hear it. Not a roar. Not even a growl. It’s a high-pitched, frantic twittering that sounds more like a flock of birds than a pack of apex predators. If you didn’t know any better, you’d think it was cute.

But you’d be wrong.

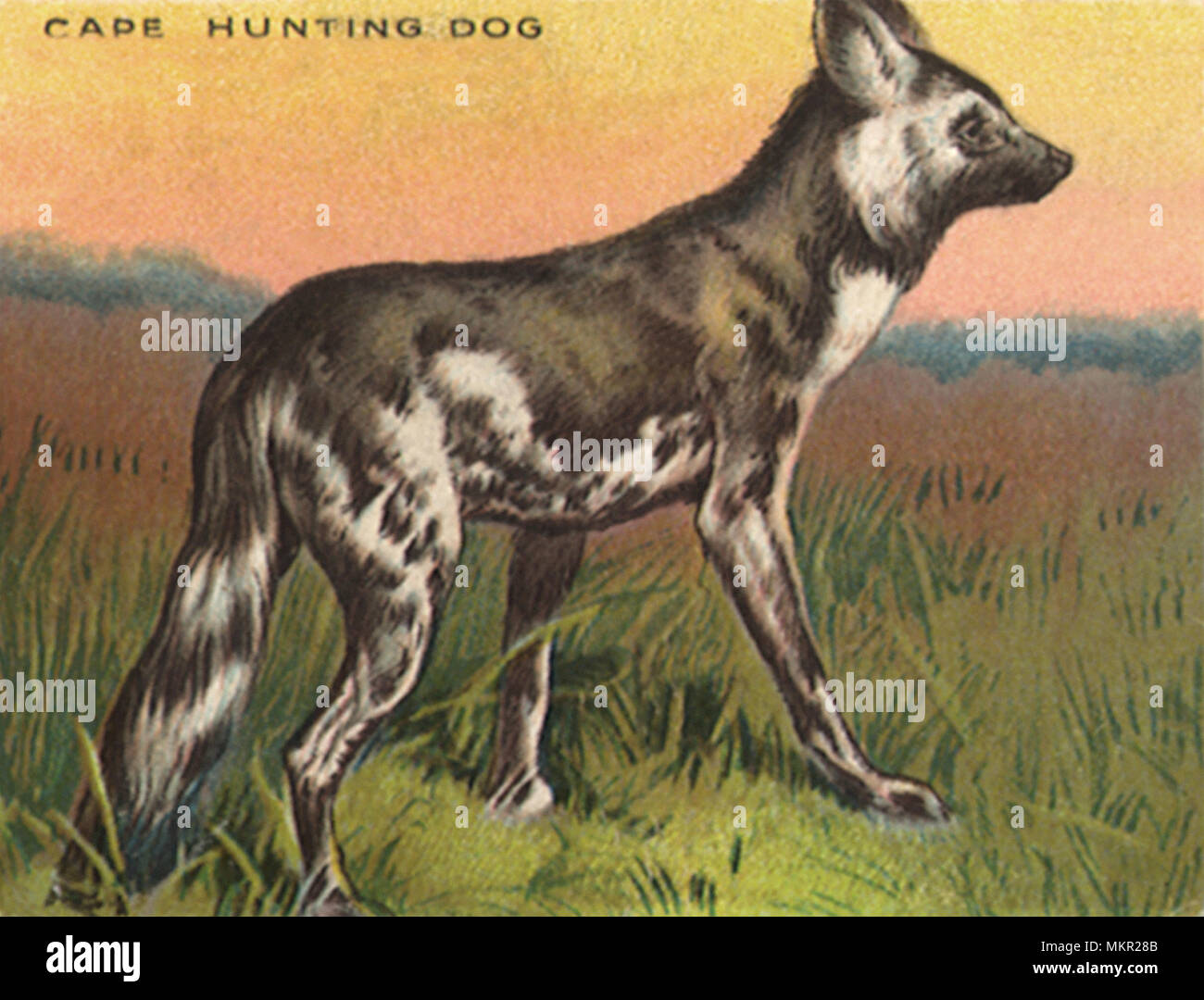

That sound is the preamble to one of the most efficient killing machines on the planet. I’m talking about the Cape hunting dog. Some people call them Painted Wolves, others call them African Wild Dogs, and scientists call them Lycaon pictus. Whatever the name, they are arguably the most misunderstood creatures in the African bush. Honestly, they’ve been given a bad rap for decades as "cruel" or "messy" hunters, but when you look at the actual cape hunting dog facts, a much more complex, almost human-like picture starts to emerge.

The Democracy of the Sneeze

Most people think of wolf packs as strict dictatorships. You’ve got the alpha, and everyone else just falls in line, right?

With Cape hunting dogs, it's way more interesting. They actually vote.

Back in 2017, researchers including Reena Walker and Dr. Neil Jordan noticed something weird during the "social rallies" these dogs hold before a hunt. The dogs would start sneezing. A lot. It turns out these aren't just hay fever or clearing dust. They are casting ballots.

If the pack is deciding whether to head out and hunt, they need a "quorum." Basically, a certain number of sneezes has to be reached before the group moves. Here’s the kicker: if the alpha pair wants to go, they only need a few sneezes to get the party started. But if a subordinate dog wants to initiate a hunt? They need way more—usually about ten sneezes—to convince the rest of the group to get off their butts. It’s a weighted democracy. It’s sophisticated. And it’s something you won't see in almost any other carnivore.

Why They Are the Ultimate Success Story (and Why Lions Fail)

Lions are the kings of the jungle, sure. But as hunters? They’re kinda mediocre. A lion’s success rate usually hovers around 25% to 30%. They’re heavy, they overheat quickly, and they rely on ambush.

💡 You might also like: North Holland The Netherlands: Why You’re Probably Visiting the Wrong Places

Cape hunting dogs are different. They are endurance athletes.

When a pack targets an impala, they don't just jump out and hope for the best. They engage in a high-speed game of tag that can last for kilometers. They can maintain a clip of 37 to 44 mph for incredible distances. Because they have a heart that’s about 15% larger than a domestic dog’s relative to their size, they just... don't... stop.

The Efficiency of the Pack

The stats are actually terrifying if you're an antelope:

- Success Rate: Between 60% and 90% of their hunts end in a kill.

- Speed: Sprints up to 44 mph.

- Dinner Time: A pack can finish an entire carcass in under 15 minutes.

They have to eat fast because they are low on the totem pole. Hyenas and lions are notorious for "kleptoparasitism"—basically just walking up and stealing the dogs' hard-earned meal. Because the dogs aren't built for a heavyweight fight, they’ve evolved to be the fastest eaters in the wilderness.

Social Bonds That Put Humans to Shame

One of the most heart-wrenching cape hunting dog facts involves how they treat their own. In many predator species, if you get sick or injured, you’re dead weight. You get left behind.

Not these guys.

The pack is a tight-knit family. They have been observed caring for elderly members who can no longer hunt and "nursing" injured dogs back to health by bringing them food. When the pack returns from a successful hunt, the dogs that stayed behind to guard the pups (the "babysitters") are the first to be fed. The hunters will regurgitate meat for them and the pups.

It's a selfless system.

Usually, only the alpha male and female breed. This might seem unfair, but it’s a survival strategy. By having only one litter to care for, the entire pack (which can range from 2 to 40 individuals) can focus all their energy on making sure those specific pups survive. It takes a village, literally.

The "Painted" Mystery of Their Coats

No two Cape hunting dogs look the same. Their scientific name, Lycaon pictus, literally means "painted wolf." Their coats are a chaotic, beautiful swirl of yellow, black, and white.

📖 Related: Weather in Woodland WA: What Most People Get Wrong

Each pattern is as unique as a human fingerprint.

Biologists actually use these patterns to track individuals in the wild. If you’re on safari and you see a pack, look at their tails. Almost all of them have a white tip. This acts like a "follow me" flag in the tall grass during a hunt. It keeps the pack coordinated when things get chaotic.

Why 2026 is a Critical Year for Survival

We have to talk about the elephant in the room. Or rather, the lack of dogs in the room.

As of early 2026, there are fewer than 7,000 African wild dogs left in the wild. Some estimates put the number of "mature" breeding individuals as low as 1,400. They are officially Endangered, and they’ve been wiped out from much of their historical range.

The Modern Threats

It’s not just habitat loss. It’s more personal than that.

- Disease: Because they are so social, a single case of canine distemper or rabies—often caught from domestic dogs in nearby villages—can wipe out an entire pack in days.

- Human Conflict: Farmers often shoot them on sight, fearing for their livestock, even though studies show these dogs rarely target domestic animals if wild prey is available.

- Snares: They are frequent victims of wire snares set by poachers for bushmeat. Because the dogs are so loyal, if one dog gets caught, the others often stay nearby to help, leading to even more dogs getting trapped.

Expert Insight: The Habitat Generalists

You’ll find them in the deserts of Namibia, the woodlands of Botswana, and the mountains of Ethiopia. They aren't picky about where they live; they are picky about how much space they have. A single pack needs a massive territory—sometimes up to 800 square miles.

This is the biggest hurdle for conservation. As humans expand, we fragment these territories. A dog trying to find a mate in 2026 often has to cross roads or farmland, which rarely ends well.

How You Can Actually Help

If you're looking to turn these cape hunting dog facts into action, start by supporting organizations that focus on "corridor conservation." Groups like Wildlife ACT or the African Wildlife Conservation Fund work on the ground to create safe passages between protected areas. This allows packs to meet and breed without the risk of inbreeding or human-wildlife conflict.

When booking a safari, choose operators that contribute directly to wild dog monitoring programs. In places like Madikwe or the Selous (Nyerere National Park), your tourism dollars literally pay for the collars and the vets that keep these packs alive.

Next time you hear someone call them "cruel" because of how they hunt, tell them about the sneezing. Tell them about the babysitters. Tell them about the 15% larger heart. These aren't just "wild dogs"—they are a masterpiece of social evolution that we can’t afford to lose.

💡 You might also like: Beaver Dam Czech Republic: Why the Landscape is Changing Faster Than You Think

Practical Steps for Wildlife Enthusiasts:

- Use apps like MammalMAP to record sightings if you are in the field; citizen science is huge for tracking fragmented populations.

- Support "One Health" initiatives that vaccinate domestic dogs in buffer zones around national parks to prevent disease spillover.

- Educate others on the distinction between the Canis genus (wolves/dogs) and the Lycaon genus to highlight their unique evolutionary path.