It is a jagged, black tooth of rock sticking out into the scream of the Southern Ocean. Honestly, if you look at cape horn on the map, it doesn’t look like much. It’s just a tiny smudge at the bottom of the Tierra del Fuego archipelago, the southernmost tip of South America. But that smudge is responsible for more shipwrecks and ghost stories than almost anywhere else on the planet. Sailors call it the "Mount Everest of sailing." It’s the place where the Pacific and Atlantic oceans decide to have a violent, never-ending fistfight.

For centuries, if you wanted to get from New York to San Francisco, you didn't have a choice. You went around the Horn. There was no Panama Canal. No shortcuts. Just thousands of miles of open water where the wind builds up speed around the entire globe without hitting a single piece of land until it slams into the Andes.

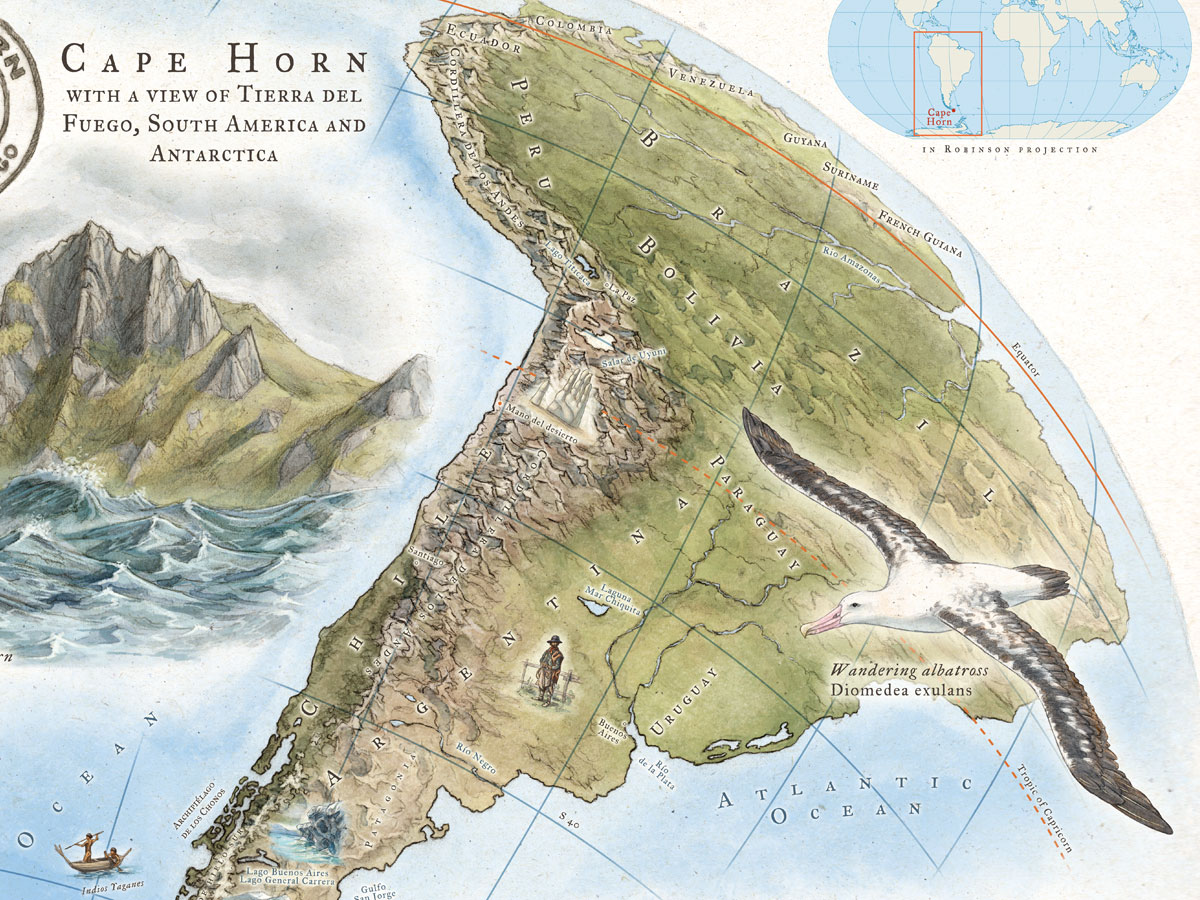

Locating Cape Horn on the Map and Why It’s Geographically Weird

Zoom in on a digital map. You’ll see the Drake Passage. This is the 500-mile-wide stretch of water between South America and the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica. It’s a funnel. A massive, geological bottleneck.

When you find cape horn on the map, you're looking at the Hornos Island. It isn't actually part of the mainland. It’s the southernmost headland of the Cape Horn archipelago. Because the continental shelf shallows up so abruptly here—going from thousands of feet deep to just a few hundred—the massive swells of the Southern Ocean are forced upward. They turn into "rogue waves" that can reach 100 feet tall.

It’s scary.

The wind is the other part of the equation. Because of the "Roaring Forties" and "Furious Fifties" (the latitudes), the wind almost always blows from the west. When that wind hits the tip of the Andes mountains, it creates a physical pressure cooker. Meteorologists call it a "corner effect." Basically, the wind gets squeezed and accelerates to hurricane speeds even on a "clear" day.

The Real Coordinates

If you're punching it into a GPS, you're looking for 55°58′48″S 067°17′21″W. It’s technically in Chilean territory. If you ever visit, you’ll find a small station manned by a Chilean Navy officer and their family. They live there in the middle of the wind for a year at a time. Talk about a lonely job.

The Sailor’s Graveyard: A History of Not Making It

People used to say that once you sailed around the Horn, you earned the right to wear a gold hoop earring and eat with one foot on the table. It was a badge of survival. Between the 16th and 20th centuries, an estimated 800 ships were lost here. Over 10,000 sailors died.

The Dutch explorer Willem Schouten named it Kaap Hoorn in 1616 after his home city of Hoorn. He wasn't the first to see it—Sir Francis Drake had drifted down that way in 1578—but Schouten gets the credit for naming the beast.

Before the Panama Canal opened in 1914, this was the primary trade route for gold, grain, and Chilean nitrates. The "Tall Ships" or "Windjammers" of the late 1800s were the kings of this route. Imagine being 100 feet up a mast, fingers frozen blue, trying to furl a frozen canvas sail while the ship pitches 40 degrees in a snowstorm. That was Tuesday for these guys.

Captain William Bligh tried to round the Horn in the Bounty for 31 days. He failed. He eventually gave up and sailed all the way around Africa to get to the Pacific. When a legendary captain like Bligh can’t make it, you know the geography is working against you.

👉 See also: Why Taking Sea Caves at Arthur Park Photos is Harder Than You Think

Modern Sailing and the Vendée Globe

You might think that in 2026, with carbon fiber hulls and satellite weather tracking, the Horn is easy.

It isn’t.

It’s still the ultimate test for professional racers in events like the Vendée Globe (a solo, non-stop round-the-world race). These sailors see cape horn on the map as the light at the end of the tunnel. Once you pass it, you’re finally leaving the Southern Ocean and heading "north" toward home. But getting there is a nightmare. In the 2020-2021 race, several skippers faced breakage and near-disasters just miles from the Cape.

The water temperature stays around 40°F (5°C). If you go overboard, you don’t have long. Even with modern survival suits, the sheer violence of the water makes rescue almost impossible.

What Most People Get Wrong About the Tip of South America

A lot of people think Ushuaia is the southernmost point. It’s a city in Argentina, and it markets itself as Fin del Mundo (The End of the World). It’s a great city. But it’s not the end.

- The False Cape Horn: About 35 miles northwest of the real thing is Falso Cabo de Hornos. In the days of sail, many captains mistook this for the real Cape, turned north too early, and crashed into the Wollaston Islands.

- The "Southernmost" mainland: The actual southernmost point of the South American mainland is Cape Froward. Cape Horn is on an island.

- The Weather: It’s not always a hurricane, but it’s always unpredictable. You can have a flat calm and a Force 10 gale within the same four-hour window.

The Albatross Monument

There’s a monument on the island. It’s a massive steel silhouette of an albatross. It commemorates the souls of the sailors who died trying to round the Horn. There’s a poem by Sara Vial inscribed nearby. It says that the souls of the dead sailors are carried in the wings of the albatross.

Sailors are superstitious. Even today, many won't whistle on deck near the Cape for fear of "whistling up a wind."

How to Actually See Cape Horn Today

You don't have to be a grizzled sea captain to see cape horn on the map in person. But it’s still an expedition.

- Expedition Cruises: Companies like Australis run specialized small-ship cruises out of Ushuaia or Punta Arenas. They use Zodiac boats to ferry you to the island.

- The "Landing" gamble: You are never guaranteed a landing. If the swell is too high, the Zodiacs can’t dock. You just look at the rock from the deck and toast with a glass of whiskey.

- Paperwork: You’re in Chile. Even though you’re coming from Argentina usually, you need your passport. The navy officer there will even stamp it for you if you make it to the lighthouse.

The lighthouse itself is tiny. It’s not the grand stone towers you see in Maine. It’s a functional, metal-framed light. Next to it is the modest house where the lightkeeper lives. They grow vegetables in a small greenhouse because nothing grows outside in the salt spray and wind.

Technical Reality: Why the Panama Canal Didn't Kill the Route

When the Panama Canal opened, Cape Horn became a relic for commercial shipping. Or so people thought.

Actually, "Post-Panamax" ships—huge tankers and bulk carriers that are too wide for the canal locks—still have to go the long way. If a ship is too big for the ditch, it’s back to the Horn. Also, canal fees are expensive. If fuel prices are low and time isn't an issue, some shipping companies still choose the southern route.

It’s a math problem. Distance vs. Dollars.

Navigating the Cape: Actionable Tips for the Brave

If you are planning to sail this or even just take a cruise, here is what you actually need to know.

💡 You might also like: El Tovar Hotel Grand Canyon Restaurant: What Most People Get Wrong

First, gear matters. This isn't a Caribbean cruise. You need "expedition grade" layers. Gore-Tex isn't a luxury; it's a requirement. The wind will find every gap in your clothing.

Second, timing is everything. The best window is the Southern Hemisphere summer (December to February). Even then, expect 40-knot winds. If you go in June, you're dealing with nearly 20 hours of darkness and ice on the decks.

Third, respect the Chilean Navy. They manage these waters with an iron fist for a reason. If they tell your captain the Drake Passage is closed, it’s closed.

Final Geographical Check

When looking at cape horn on the map, don't just look at the point. Look at the bathymetry (the depth of the ocean floor). See how the deep blue of the Pacific turns into a light turquoise shelf right at the Horn? That is the visual representation of the "shallows" that create the killer waves.

Understanding that transition is the difference between seeing a map and understanding a landscape.

To experience the Horn is to realize how small we are. We have satellites and nuclear-powered engines, but a 60-foot wave at the bottom of the world doesn't care about your tech. It’s one of the few places left on Earth where nature hasn't been "tamed" in the slightest.

Next Steps for Your Journey:

- Check current maritime weather charts for the Drake Passage to see the real-time wave heights.

- Look into the "Cape Horners" archives if you suspect an ancestor was a merchant sailor; many crew lists are still preserved.

- If you're booking a trip, ensure the vessel is an "expedition" class ship with a reinforced hull, as standard cruise liners often avoid the Cape entirely due to stability issues in high swells.