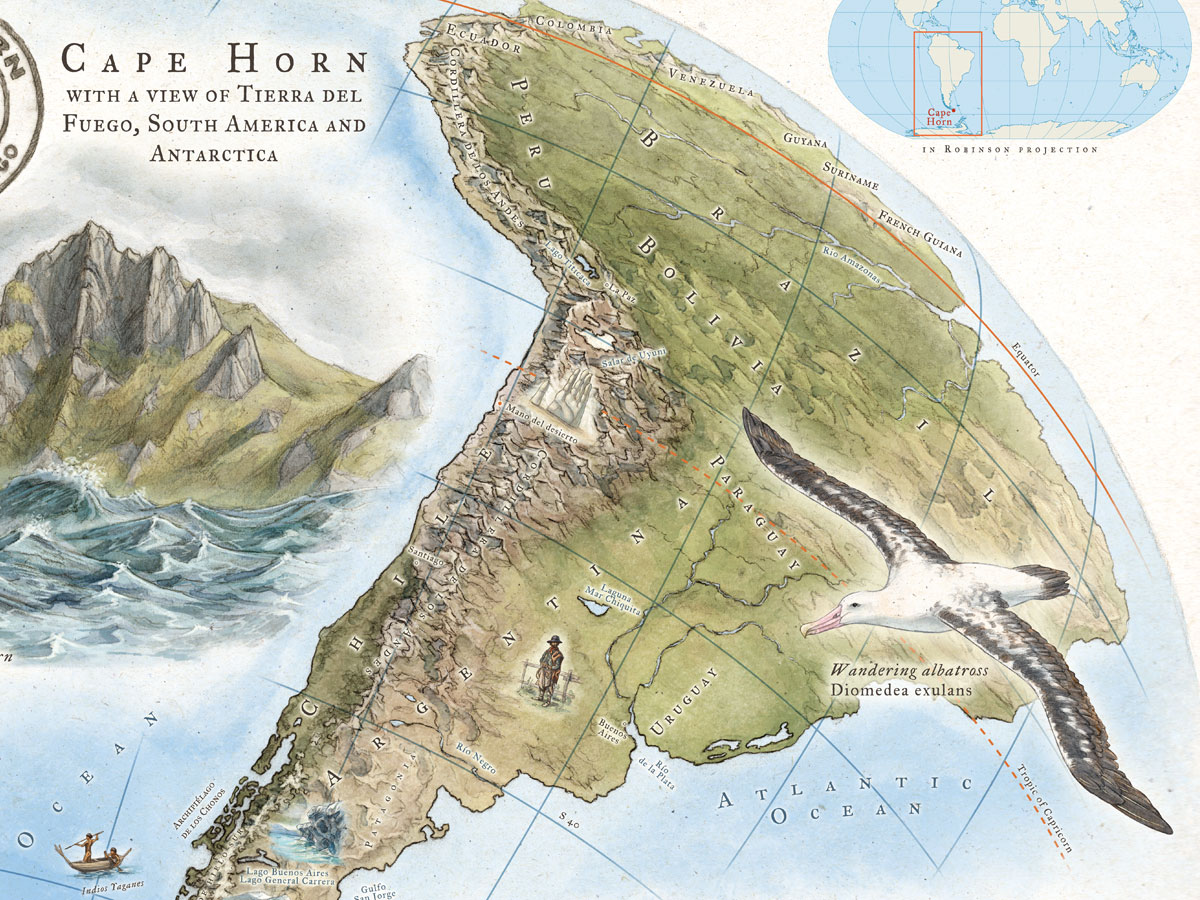

If you look for cape horn on a map, you’ll find it dangling off the bottom of South America like a jagged, lonely teardrop. It’s located on Hornos Island in the Hermite Islands group. It isn't even the southernmost point of the South American continental shelf—that honor belongs to the Diego Ramírez Islands—but for centuries, "The Horn" has been the Everest of the ocean. It’s the place where the Atlantic and Pacific oceans don't just meet; they collide with a violence that has claimed over 800 ships and 10,000 lives. Honestly, it’s a graveyard.

Most people assume the danger is just about the cold. It’s not. When you find cape horn on a map, you’re looking at a geographical choke point. There is no land circling the globe at that specific latitude, around 56 degrees south. This means the wind and waves can whip around the entire planet without hitting a single obstacle until they smash into the Andean mountains. It’s a literal funnel. The water gets pushed through the Drake Passage, and because the sea floor rises abruptly from the deep ocean to a shallow shelf, the waves become massive, steep, and unpredictable. They call them "greybeards." They can reach 30 meters high. That’s a ten-story building made of freezing saltwater moving at forty miles per hour.

Finding Cape Horn on a Map: The Geography of a Nightmare

To really understand what you're seeing when you locate cape horn on a map, you have to zoom out. Look at the Drake Passage. It’s the 500-mile-wide stretch of water between the tip of South America and the South Shetland Islands of Antarctica. It’s the narrowest point in the Southern Ocean. For a sailor in the 1800s, this was the only way to get from New York to San Francisco without trekking across the entire United States on foot or by horse. You had to go around.

The Dutch navigators Jacob Le Maire and Willem Schouten were the first Europeans to round it in 1616. They named it Kaap Hoorn after the city of Hoorn in the Netherlands. Before that, everyone used the Strait of Magellan. But the Strait of Magellan is a narrow, winding nightmare of its own, full of fickle winds and hidden rocks. Open sea seemed better. It wasn't.

If you’re looking at a digital map today, you’ll notice the terrain of the Wollaston and Hermite islands is incredibly rugged. This isn't a sandy beach. It’s black basaltic rock, sheer cliffs, and stunted greenery that looks like it's been screaming in the wind for a century. Because it has. The weather here is famously terrible. It rains or snows about 280 days a year. Fog is the default setting. Sailors would spend weeks, sometimes months, trying to "beat" to the west against the prevailing winds. Some ships would get within sight of the Pacific, only to be blown 200 miles back into the Atlantic by a sudden Antarctic gale.

✨ Don't miss: What Time in South Korea: Why the Peninsula Stays Nine Hours Ahead

The Physics of the "Great Southern Graveyard"

Why is the water so uniquely bad here? It’s basically a massive drainage problem. The Antarctic Circumpolar Current carries a volume of water roughly 150 times the flow of all the world's rivers combined. When this massive volume of water is squeezed through the Drake Passage, it accelerates.

Then there’s the shelf effect.

In the open ocean, waves have deep roots. But as that energy hits the continental shelf near the Horn, the bottom of the wave drags, and the top keeps going. This creates those vertical faces that can snap a mast like a toothpick. Even modern racing yachts in the Vendée Globe—the toughest solo around-the-world race—treat cape horn on a map as the ultimate milestone. Passing it means you’ve survived the Southern Ocean, but getting there is a gamble every single time.

Is Cape Horn Still Relevant Today?

You’d think the Panama Canal would have made the Horn a footnote in history. To a degree, it did. When the canal opened in 1914, the treacherous route around the tip of South America became optional for most commercial trade. But "optional" doesn't mean "unused."

🔗 Read more: Where to Stay in Seoul: What Most People Get Wrong

Giant tankers and bulk carriers that are "Capesize"—meaning they are too large to fit through the Panama or Suez canals—still have to take the long way. If you track these ships, you'll see their icons hovering near cape horn on a map on sites like MarineTraffic. These vessels are steel monsters, often over 1,000 feet long, and even they take a beating in these latitudes.

Then there’s the tourism. It’s weird to think about, but people pay thousands of dollars to go there now. Expedition cruise ships out of Ushuaia, Argentina, or Punta Arenas, Chile, attempt "landings" on Hornos Island. It’s rarely a guarantee. The wind is often too high to launch the rubber Zodiac boats. If you do manage to get ashore, you’ll see the famous Albatross Monument. It’s a silhouette of an albatross in flight, a tribute to the souls of sailors lost at sea. Legend says the albatrosses circling the Horn are the ghosts of those drowned mariners.

What the Map Doesn't Tell You

The map shows a coordinate: 55°58′48″S 067°17′21″W.

What it doesn't show is the psychological toll. The "Roaring Forties," "Furious Fifties," and "Screaming Sixties" aren't just clever nicknames for latitudes. They describe the sound of the wind in the rigging. It’s a low-frequency hum that vibrates through the hull of a boat. Captains like William Bligh (of Bounty fame) spent thirty days trying to round the Horn before finally giving up and sailing all the way around the world the other way via the Cape of Good Hope. Imagine that. You’re so beaten by a single point on the map that you decide to sail 10,000 extra miles just to avoid it.

💡 You might also like: Red Bank Battlefield Park: Why This Small Jersey Bluff Actually Changed the Revolution

Key Landmarks Near Cape Horn

If you are studying cape horn on a map for a trip or research, keep an eye out for these specific markers:

- The Lighthouse: There are actually two. One is a small fiberglass tower, and the other is the "End of the World" lighthouse (Faro de Cabo de Hornos), which is manned by a Chilean Navy officer and their family. They live there for a year at a time. Talk about isolation.

- Stella Maris Chapel: A tiny wooden chapel near the lighthouse. It’s probably the most humble, wind-battered place of worship on Earth.

- False Cape Horn: About 35 miles to the northwest on Hoste Island. In the days of sail, many captains mistook this for the real Horn. They would turn north too early, get trapped in the labyrinth of the Wollaston Islands, and wreck their ships on the rocks.

How to Virtually or Physically Explore the Area

Honestly, most of us will only ever see cape horn on a map, and that’s probably for the best. If you want to dive deeper, use Google Earth to look at the "Kelp Forests" around the islands. The water is so clear and cold that the kelp grows in massive, thick stalks that can actually foul a ship's propeller.

If you're planning a real visit:

- Fly to Ushuaia: It’s the southernmost city in the world (though Chile disputes this with Puerto Williams).

- Book an Expedition: Look for "Cape Horn" specific itineraries. These usually happen between November and March, which is the "summer" down there. It’ll still be 40 degrees Fahrenheit.

- Prepare for No Landing: Even the best captains can't fight a 60-knot gust. You might just see the rock from the balcony of the ship.

The reality of cape horn on a map is that it represents the raw, unedited power of the planet. It’s one of the few places left where technology doesn't make you the boss. You’re just a guest, and a temporary one at that.

To get a better sense of the scale, open a maritime chart of the Drake Passage. Note the soundings (the depth numbers). Watch how the depth jumps from 4,000 meters to 100 meters in a very short distance. That’s the "step" that creates the monster waves. If you're interested in the history, look up the logs of the Flying Cloud or the Cutty Sark. These clipper ships used to run the "Eastward" route, using the Horn’s ferocious winds to propel them at speeds that were unthinkable in the mid-1800s. They were basically surfing the most dangerous waves on Earth for profit.

Next Steps for Your Research:

- Compare the distance of the Panama Canal route versus the Cape Horn route for a journey from New York to Seattle; you’ll see it adds roughly 8,000 nautical miles.

- Check the live weather at the Diego Ramírez Islands weather station to see the current wind speeds at the "Gate of the Horn."

- Look up the "Cape Horners" (A.I.C.H.) associations, which were historically exclusive clubs for sailors who had successfully rounded the point on a sailing ship.