You’re halfway through a long run when that familiar, dull ache creeps in behind your kneecap. It’s not a sharp "stop right now" kind of pain, but it’s definitely there. Persistent. Annoying. You probably know it as Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFPS), but most of us just call it runner's knee. Honestly, the first instinct for most of us is to just grit our teeth and push through it, fearing that if we stop, we'll lose all that hard-earned cardio. But is it actually okay to run with runners knee, or are you just fast-tracking a date with a surgeon?

It depends.

That’s the frustrating answer you’ll get from most sports docs. But let's get into the weeds of why it depends and how you can actually tell if your knee is "safe" sore or "danger" sore.

The Truth About Trying to Run With Runners Knee

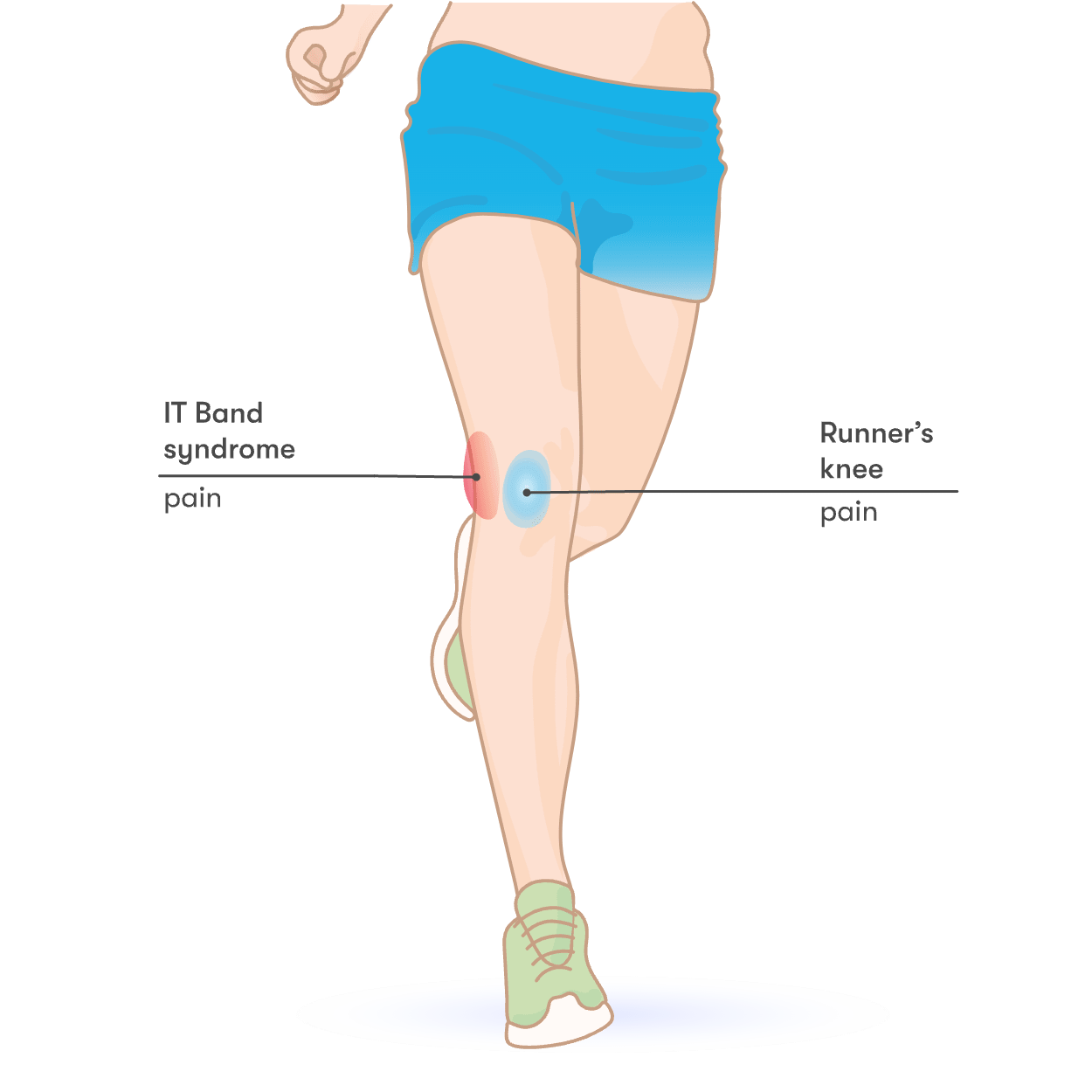

First off, runner's knee isn't usually a structural failure. Your ACL isn't snapped. Your meniscus probably isn't shredded. It’s a tracking issue. Think of your kneecap (the patella) like a train and the groove in your femur like the tracks. When things are working, the train stays centered. When you have PFPS, the train is rubbing against the side of the track. Ouch.

Can you keep going?

Most clinical research, including a landmark study published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, suggests that "relative rest" is better than total rest. If you stop moving entirely, your muscles atrophy, and the problem actually gets worse. You need to find the "sweet spot."

Pain is your dashboard light.

If your pain is a 2 or 3 out of 10? You’re likely fine to keep a modified schedule. If it hits a 5? You need to walk. If it lingers into the next morning or makes you limp while walking to the bathroom, you’ve crossed the line. It's basically a game of volume management. You aren't "injured" in the way a broken bone is injured; you're "overloaded."

Why Your Glutes Are Actually the Problem

Weirdly enough, the pain in your knee often has nothing to do with your knee.

👉 See also: Understanding MoDi Twins: What Happens With Two Sacs and One Placenta

I talked to a physical therapist recently who told me that 80% of the people she sees for run with runners knee issues actually have "sleepy" glutes. When your gluteus medius—that muscle on the side of your hip—is weak, your thigh bone (femur) rotates inward every time your foot hits the pavement. This forces the kneecap out of its groove.

Basically, your hip is the steering wheel, and your knee is just a passenger along for the ride.

If the steering is off, the passenger gets smashed into the door. Strengthening the hips is almost always the "secret sauce" for getting back to high mileage. We're talking about monsters walks, clamshells, and single-leg squats. Boring? Yes. Effective? Incredibly.

The Footwear Fallacy and Surface Tension

Let's talk about shoes for a second. Everyone wants to buy a $200 pair of carbon-plated super shoes to fix the problem. Don't.

While a change in footwear can sometimes help, especially if you’re running in shoes that are 500 miles past their expiration date, it’s rarely the magic bullet. However, the surface you run on matters immensely. Concrete is unforgiving. If you're struggling to run with runners knee, try moving your sessions to a synthetic track or a flat dirt trail. The slight "give" in the surface reduces the peak impact force traveling up your tibia.

Also, watch your downhill running.

Running downhill increases the eccentric load on the quadriceps, which pulls the patella harder against the femur. It’s like sandpapering your joint. If you're in a flare-up, stick to the flats or, better yet, do some uphill power walking. It gets the heart rate up without the "clunk" of the downhill strike.

Cadence: The One Fix Nobody Does

If you want to keep running while you heal, you have to change your mechanics. Most runners have a cadence (steps per minute) that is too slow. They overstride. They land with their foot way out in front of their body, acting like a brake.

✨ Don't miss: Necrophilia and Porn with the Dead: The Dark Reality of Post-Mortem Taboos

This sends a massive shockwave straight to the kneecap.

Try this: increase your cadence by just 5% to 10%. You don't have to run faster; you just take shorter, quicker steps. This naturally moves your foot strike closer to your center of gravity. Research from the University of Wisconsin-Madison showed that even a subtle increase in step frequency significantly reduces the work required by the knee joint. It feels weird at first—kinda like you're a cartoon character—but it's the fastest way to reduce knee strain in real-time.

The Myth of "Running Through It"

We’ve all heard that "pain is weakness leaving the body" nonsense. In the case of PFPS, pain is actually your nervous system trying to protect you. If you ignore it long enough, your brain will start changing how you move to avoid the pain.

You’ll start shrugging your hip or leaning to one side.

This is how a simple case of runner's knee turns into a hip flexor strain or a stress fracture in the opposite foot. You're compensating. Honestly, the smartest runners are the ones who know when to bail on a workout. If you can't maintain your normal form, the workout is over. Period.

Inflammation vs. Irritation

Is it worth icing?

Ice is great for numbing the area so you can get through your day, but it doesn't "cure" the tracking issue. Same goes for ibuprofen. It masks the signal. If you take four Advil and go for a 10-miler, you aren't healing; you're just silencing the alarm while the house is on fire.

Use ice after a run if it feels good, but don't use it as a tool to enable more mileage than your body is ready for.

🔗 Read more: Why Your Pulse Is Racing: What Causes a High Heart Rate and When to Worry

Instead, focus on soft tissue work. Use a foam roller on your quads and TFL (tensor fasciae latae). If those muscles are tight, they act like tight guitar strings, pulling the kneecap out of alignment. Loosening the "ropes" around the knee is often more effective than icing the joint itself.

A Practical Return-to-Run Protocol

If you’ve taken a few days off and want to test the waters, don't just head out for your usual loop. You need a structured test.

- The Squat Test: Can you do 15 bodyweight squats without pain? If no, you aren't ready to run.

- The Hop Test: Can you hop on the affected leg 10 times without that sharp "pinch" feeling?

- The 1-Minute Rule: Start with a walk-run interval. Run for 1 minute, walk for 1 minute. Do this for 10-15 minutes.

- The 24-Hour Check: How does it feel tomorrow? If it’s stiff or sore, you did too much.

This gradual loading is how you build "tissue tolerance." Your knee needs to learn how to handle weight again, and you can't rush biology.

Beyond the Run: Cross-Training That Actually Helps

When you can't hit the pavement, you need to maintain your engine. The elliptical is usually the safest bet because it mimics the running motion without the impact. However, some people find the elliptical actually irritates the knee because of the constant "gliding" motion.

Swimming or "aqua jogging" is the gold standard, but let's be real—hardly anyone actually does it because it's boring as hell.

A better alternative? High-resistance cycling. Keep the RPMs around 80-90. Don't "mash" big gears, as that puts a lot of torque on the patella. Keep it light and fast. It keeps the blood flowing to the joint, which is crucial because cartilage doesn't have its own blood supply. It relies on movement to "pump" nutrients in and out.

Actionable Steps for Recovery

Stop searching for a "quick fix" and start looking at your movement patterns. If you're serious about getting back to your peak, follow these steps:

- Assess your cadence: Use a running watch to find your current steps per minute. Aim to increase it by 5% on your next run.

- Strengthen the "Side Body": Incorporate lateral lunges and side-lying leg raises three times a week. Target the glute medius specifically.

- Check your hips: If you sit at a desk all day, your hip flexors are likely tight, which tilts your pelvis forward and puts extra stress on the knees. Stretch your couch-stretch style.

- Audit your mileage: Did you recently increase your distance by more than 10% in a week? If so, back off to your "last known good" volume.

- Listen to the "Ache": If the pain is sharp or causes swelling, see a doctor. If it's a dull ache that warms up as you move, you're likely in the "safe to rehab" zone.

The goal isn't just to run with runners knee today; it's to be able to run five years from now without needing a knee replacement. Be patient. Your future self will thank you.