You’ve seen the movies. A massive shadow glides beneath a tiny boat, followed by a set of jaws wide enough to swallow a suburban SUV. People love the idea of a monster lurking in the dark. It’s a primal thrill. But when we get past the CGI and the popcorn, the actual scientific question of can megalodon still exist usually hits a brick wall of cold, hard oceanography. Honestly, though, the "no" isn't just a boring dismissal—it's actually based on some of the most fascinating biological shifts our planet has ever seen.

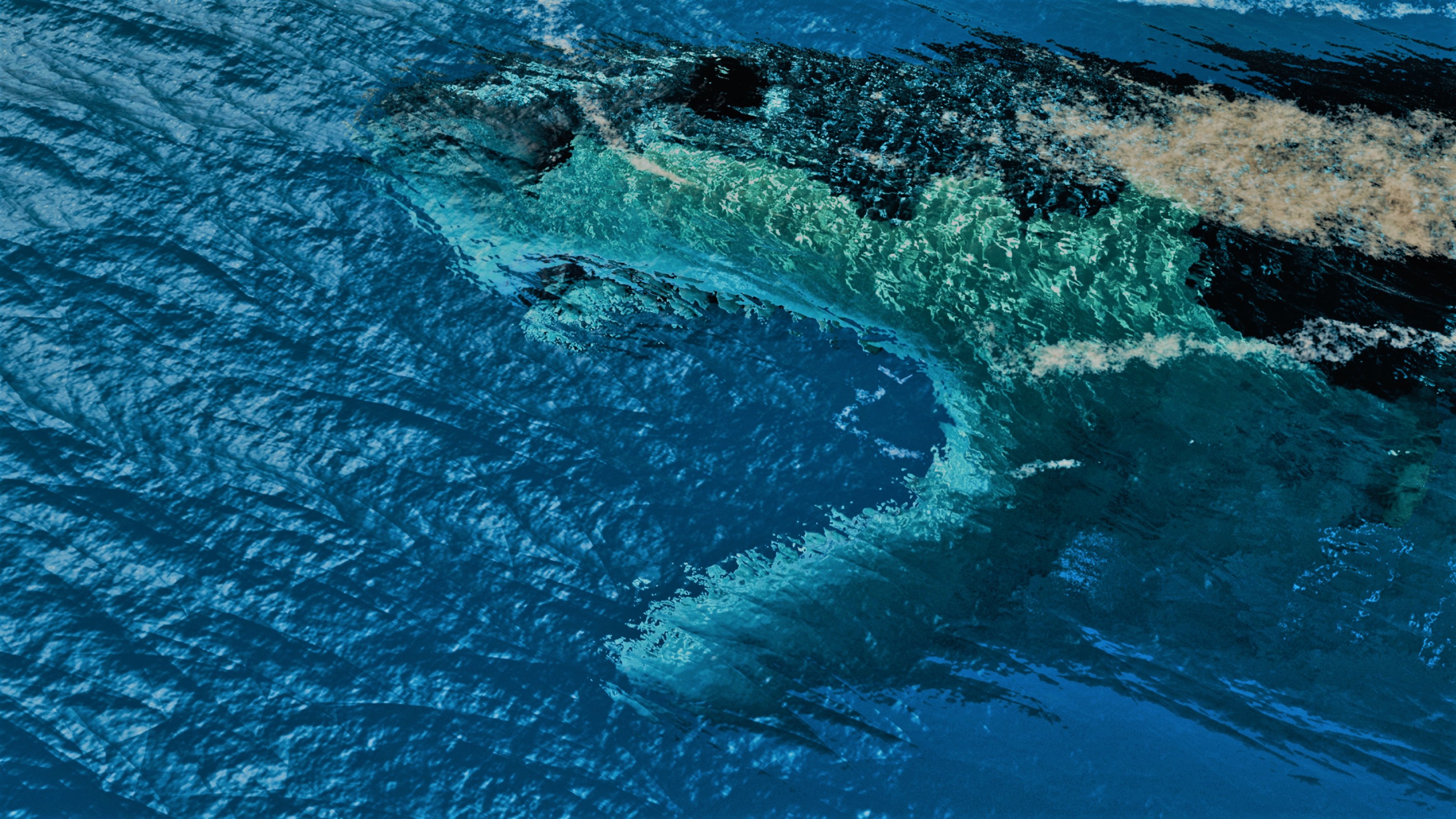

The Otodus megalodon wasn't just a big shark. It was a global apex predator that dominated for over 20 million years. Then, about 3.6 million years ago, the fossil record just... stops. No more teeth. No more vertebrae. If something that big was still swimming around, we’d see it. Or would we?

The Deep Sea Argument vs. Reality

Most folks who hope the Meg is still out there point to the Mariana Trench. "We've only explored 5% of the ocean!" is the rallying cry. It sounds logical. If we haven't seen it, maybe it's just hiding in the 95% we haven't mapped.

But here’s the thing about the deep sea: it’s an absolute desert.

Megalodons were massive. We are talking about a fish that reached lengths of 50 to 60 feet. To keep a body that size moving, you need a staggering amount of calories. High-octane fuel. In the prehistoric oceans, that fuel came in the form of small-to-medium-sized whales. These whales lived near the surface because they needed to breathe air and eat nutrient-rich plankton. If a megalodon tried to live in the Mariana Trench, it would starve in a week. There just aren’t enough giant snacks down there to support a massive, warm-blooded predator.

Also, the temperature would kill them.

Research published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences indicates that megalodons were regionally endothermic. That’s a fancy way of saying they were warm-blooded, sort of like Great Whites but even more so. This allowed them to hunt in cooler waters and swim faster, but it also meant they had a high metabolic demand. The deep ocean is hovering just above freezing. A megalodon in the abyss would be like trying to run a Ferrari in a freezer—the engine just wouldn't stay warm enough to function.

👉 See also: Yemen: Why This Is Actually the Only Country Starting with Y

What Scientists Actually Found in the Teeth

If you want to know can megalodon still exist, you have to look at their teeth. We find them everywhere. From the beaches of North Carolina to the deserts of Peru. Because sharks lose thousands of teeth in a lifetime, they leave a trail.

Scientists like Robert Boessenecker from the College of Charleston have spent years dating these fossils. When researchers re-examined the fossil record a few years ago, they realized that the Megalodon didn't die out 2.6 million years ago as previously thought, but rather closer to 3.6 million years ago. This timing is crucial. It overlaps perfectly with the rise of a new competitor: the Great White shark.

Imagine you're a giant, 50-ton shark. You're the king. But then, a smaller, faster, more efficient version of you shows up. The Great White didn't necessarily kill the Megalodon in a fight. It just ate all its food. Juvenile megalodons and adult Great Whites competed for the same prey. The smaller sharks were more adaptable, could survive on less, and eventually, the Megalodon was squeezed out of its own ecosystem. It's less of a cinematic battle and more of a slow, biological bankruptcy.

The Whale Problem

Whales are the smoking gun here.

During the Pliocene, whales started to change. They got bigger, and they started migrating toward the poles to feed in cold, nutrient-rich waters. The megalodon was trapped. While it was "warm-blooded" for a fish, it still couldn't handle the frigid Antarctic or Arctic currents where the whales were heading.

Think about it. If there were still 60-foot sharks roaming the oceans today, we would see the evidence on the whales. We see scars on whales today from Orcas and Great Whites. We have never, in the history of modern whaling or marine biology, found a whale with a bite mark consistent with a 7-foot-wide jaw. We’d also see "ship strikes" that weren't ships. We'd see massive carcasses washing up on beaches with huge chunks missing. We see none of that.

The ocean is big, sure. But it's not a secret-keeping vault. We have satellite arrays, sonar, underwater cables, and thousands of commercial vessels crossing the water every single day. Something that requires that much food cannot remain invisible.

Why We Want to Believe

So why does the question of can megalodon still exist persist?

Maybe it’s because the ocean is the last true wilderness. On land, we’ve mapped every forest and climbed every mountain. But the water is still mysterious. The discovery of the Coelacanth in 1938—a fish thought to be extinct for 65 million years—gave people hope. "If the Coelacanth survived, why not the Meg?"

🔗 Read more: Why the Oscar Wilde Burial Site is Still Covered in Lipstick and Controversy

The difference is size and niche. The Coelacanth is a small, slow-moving fish that lives in very specific, low-energy environments. It doesn't need much to survive. It’s easy to miss. A megalodon is a biological bulldozer. You can't hide a bulldozer in a backyard garden for three million years without someone noticing the tracks.

The Real Giants of 2026

If you're looking for something truly "Megalodon-esque" in the modern world, you have to look at the Orca. In many ways, Orcas are the new Megalodon. They are highly intelligent, they hunt in packs, and they are currently the undisputed rulers of the ocean. They have even been documented hunting and killing Great White sharks just to eat their livers.

Actually, the shift from Megalodon to Orcas and Great Whites shows how evolution favors efficiency over sheer size. Being the biggest isn't always the best strategy when the climate changes and food sources move.

Actionable Evidence to Track

If you want to follow the real science of whether large prehistoric creatures could still be out there, watch these specific areas of research:

- Environmental DNA (eDNA) Sampling: Scientists now take jars of seawater and sequence the DNA inside. This reveals every creature that has swum through that patch of water in the last few days. Thousands of eDNA samples are taken annually; not one has ever flagged Otodus megalodon.

- Whale Migration Patterns: Keep an eye on studies regarding the health and scarring of humpback and blue whales. They are the primary indicators of what is hunting in the open ocean.

- Isotope Analysis: New studies on the zinc isotopes in fossilized teeth are helping scientists map exactly what the Megalodon ate and how its diet differed from modern sharks.

The Megalodon is gone, but the world it left behind is still plenty dangerous and incredibly beautiful. We don't need a 50-foot ghost shark to make the ocean worth protecting; the giants we actually have are more than enough.

To stay grounded in the reality of marine biology, start by following the work of the Florida Program for Shark Research or checking the Global Shark Attack File, which catalogs every encounter between humans and sharks. You'll find plenty of fascinating data, but you won't find any monsters—just highly evolved predators trying to survive in a changing world.