It sounds like something out of a political thriller. A president picks up a pen and wipes away a crime before a prosecutor even has the chance to file paperwork. No handcuffs, no "you have the right to remain silent," and definitely no trial. It feels wrong to a lot of people, but honestly, in the eyes of American law, it's totally a thing.

So, can a president pardon someone before they are charged? Short answer: Yes. Long answer: It's one of the most absolute powers in the U.S. Constitution, and it has been used to shield people from the law before they ever stepped foot in a courtroom.

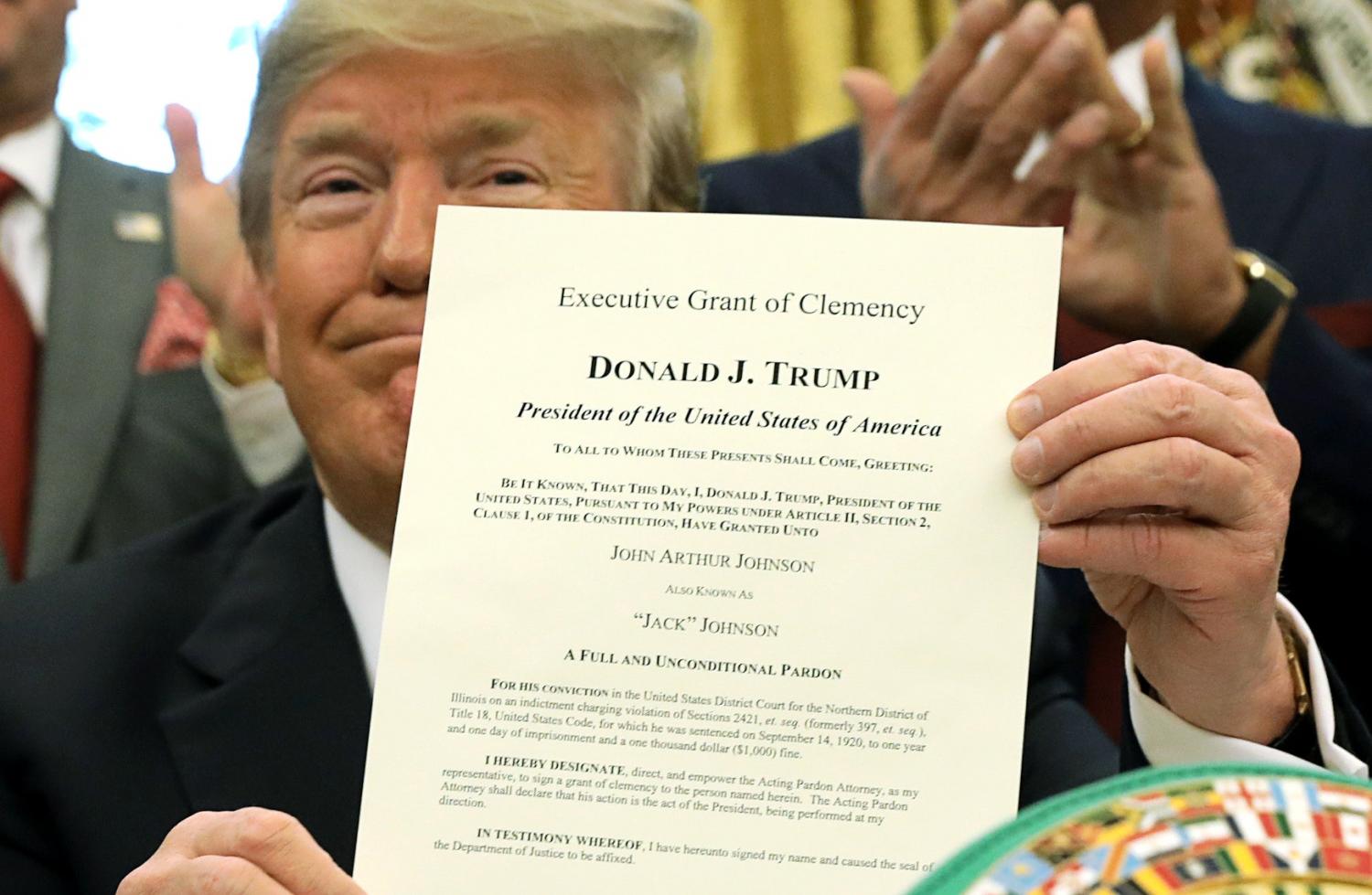

The concept is called a "preemptive pardon." While we usually see pardons happen at the very end of a presidency for people already sitting in prison cells, the law doesn't actually require a conviction. Or an indictment. Or even an arrest. Basically, if the "offense" has already happened, the president can step in.

The 1866 Case That Changed Everything

We have to look back at the aftermath of the Civil War to understand why this is allowed. There was a guy named Augustus Garland. He was a lawyer who had served in the Confederate Congress. After the war, a federal law basically tried to ban anyone who had supported the Confederacy from practicing law in federal courts.

Garland had a problem. He wanted to work, but he'd technically committed treason by siding with the South. However, President Andrew Johnson had given him a full pardon. The Supreme Court took up the case, Ex parte Garland (1866), and their ruling became the gold standard for pardon power.

The Court didn't mince words. They said the pardon power is "unlimited," except in cases of impeachment. Specifically, Justice Stephen Field wrote that the power "may be exercised at any time after [the crime's] commission, either before legal proceedings are taken, or during their pendency, or after conviction and judgment."

That one sentence changed the game. It means as long as the act—the "offense against the United States"—has already occurred, the president can grant a pardon. You can't pardon someone for a crime they might commit next Tuesday, but you can definitely pardon them for the one they committed last night, even if the FBI hasn't even opened a file yet.

✨ Don't miss: Will Palestine Ever Be Free: What Most People Get Wrong

The Most Famous Preemptive Pardon: Ford and Nixon

When people ask if can a president pardon someone before they are charged, they are usually thinking of Gerald Ford.

On September 8, 1974, President Ford sat down and signed Proclamation 4311. It gave Richard Nixon a "full, free, and absolute pardon" for all offenses against the United States which he "has committed or may have committed" during his time as president.

At that moment, Nixon hadn't been charged with a single crime. There were no indictments from the Watergate scandal hanging over his head yet, though they were certainly coming. Ford’s move was a massive gamble. He argued that the country needed to heal and that a long, drawn-out trial of a former president would keep the nation's wounds open.

It was incredibly unpopular. Ford's approval rating plummeted overnight, and many historians think it's why he lost the 1976 election. But legally? It was ironclad. Because the Supreme Court had already decided in Ex parte Garland that pardons could happen before charges, no one could successfully challenge Ford’s right to do it.

How It Works (and What It Doesn't Cover)

You've gotta realize that while this power is "plenary" (which is just a fancy legal word for absolute), it isn't a magic wand for everything. There are some hard boundaries that even a president can't cross.

Federal vs. State Crimes

This is the big one. A president can only pardon "Offenses against the United States." That means federal crimes. If you rob a bank (federal), the president can help you. If you shoplift from a local convenience store or commit a crime that is prosecuted by a District Attorney in New York or California (state), the president is powerless. Only a governor can help you there.

🔗 Read more: JD Vance River Raised Controversy: What Really Happened in Ohio

The Impeachment Exception

The Constitution explicitly says pardons can't be used in "Cases of Impeachment." This keeps a president from pardoning themselves or their allies to stop Congress from removing them from office.

The "Future Crimes" Rule

A president cannot give you a "get out of jail free" card for the future. You can't get a pardon today for a tax evasion scheme you plan to start next year. The "offense" must have already been completed for the pardon to be valid.

Jimmy Carter's Mass Pardon

Not all preemptive pardons are for high-profile politicians. On his first full day in office in 1977, Jimmy Carter issued a blanket pardon to hundreds of thousands of men who had evaded the draft during the Vietnam War. Most of these men had never been charged. They were just living in exile or in hiding. Carter’s pardon effectively told them they could come home without fear of the government ever filing those charges.

Does Accepting a Pardon Mean You're Guilty?

There’s a lot of debate about this. In a 1915 case called Burdick v. United States, the Supreme Court suggested that accepting a pardon "carries an imputation of guilt" and that "acceptance a confession of it."

However, legal experts like to point out that this was mostly "dicta"—which is basically the judge's side commentary, not the core legal ruling. In practice, people accept pardons for all sorts of reasons. Some are innocent but can't afford a trial. Others are guilty and just want to go home. While the Burdick case is often cited by critics, it hasn't really stopped anyone from taking a pardon and still maintaining their innocence in the court of public opinion.

Why Presidents Do This

It’s usually about finality. If a president knows a trial is going to be a circus or if they believe the prosecution is politically motivated, they might use a preemptive pardon to "stop the clock."

💡 You might also like: Who's the Next Pope: Why Most Predictions Are Basically Guesswork

It’s a controversial tool because it bypasses the entire judicial system. No jury gets to hear evidence. No judge gets to rule on motions. It's just one person making a decision. But that’s exactly what the Framers intended. Alexander Hamilton wrote in Federalist No. 74 that "in seasons of insurrection or rebellion, there are often critical moments, when a well-timed offer of pardon to the insurgents or rebels may restore the tranquillity of the commonwealth."

Basically, they wanted the president to have a "break glass in case of emergency" tool to keep the country from falling apart.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

If you are tracking a specific legal case or just want to stay informed on how this power might be used in the future, keep these things in mind:

- Watch the Jurisdiction: Check if the investigation is federal (FBI/DOJ) or state (DA/Attorney General). If it's state-level, a presidential pardon is irrelevant.

- Look for the Wording: A preemptive pardon usually uses broad language like "any and all offenses committed during X time period" because they don't have specific charge numbers to reference yet.

- Monitor the Acceptance: A pardon has to be accepted to be valid. In rare cases, people have actually refused pardons because they didn't want the "imputation of guilt" that comes with it.

- Check the Timing: While it can happen before charges, it almost always happens right before a president leaves office to minimize the political fallout.

The power to pardon before charges are filed is a unique feature of the American presidency. It's a remnant of the "royal prerogative" of English kings, baked into our democracy as a way to prioritize national stability over individual prosecution. Whether it's "fair" is a question for voters; whether it's "legal" was settled over 150 years ago.

To stay updated on current federal legal proceedings, you can monitor the Department of Justice’s Office of the Pardon Attorney website, which maintains a public record of all clemency actions taken by the sitting president. For state-specific matters, check the official website of your state's Governor, as pardon protocols vary significantly by jurisdiction.