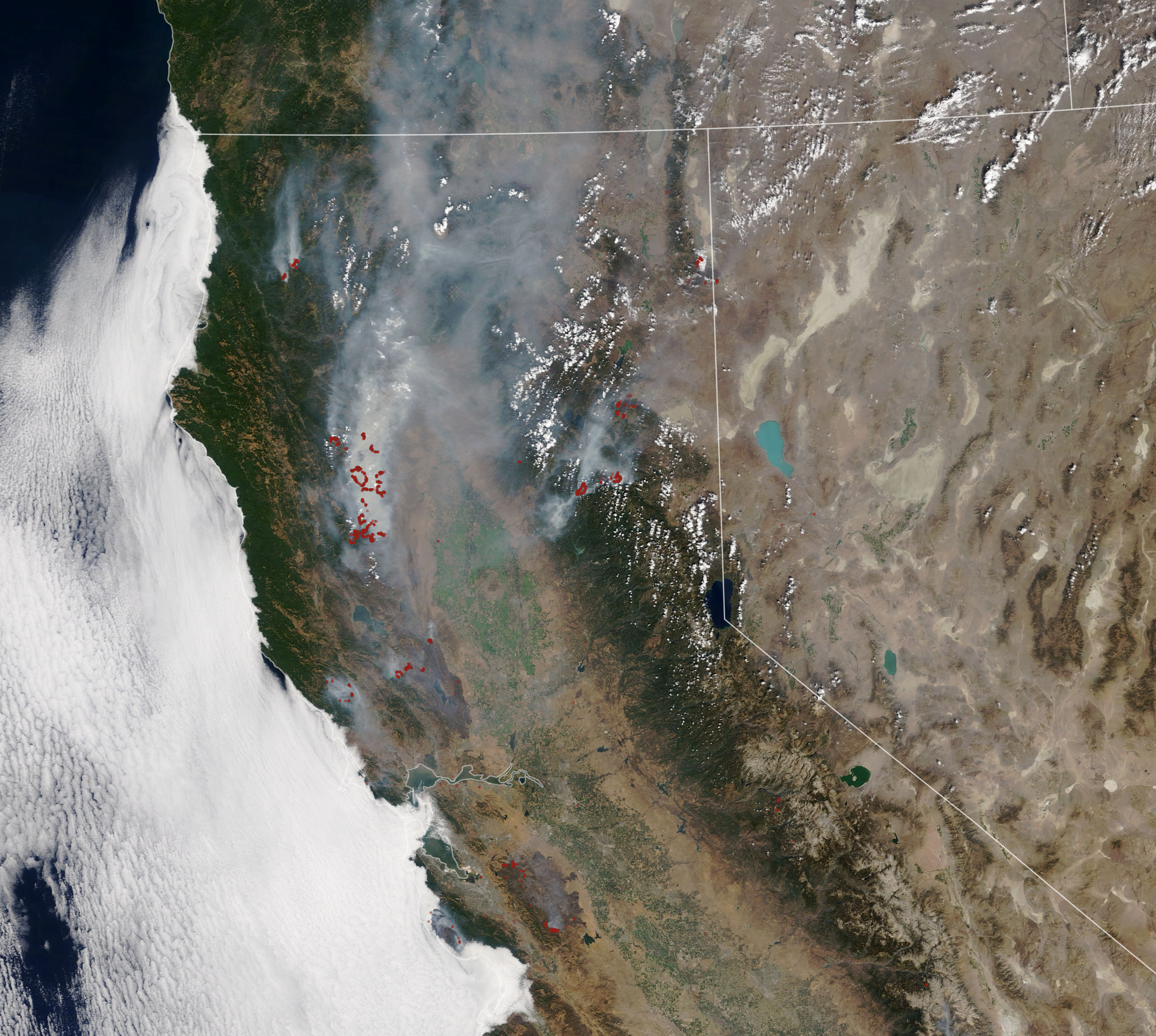

You've probably seen them on the news. Those massive, swirling plumes of brown smoke choking the Pacific coastline, or the eerie "burn scars" that look like bruises on the Earth's skin. California wildfire satellite images have become a staple of our social media feeds every summer and fall. They’re haunting. They’re beautiful in a morbid way. But honestly, most people scrolling through Twitter or checking the NASA FIRMS map don't actually know what they’re looking at.

It’s not just a photo from a high-altitude camera.

Actually, it's a complex layer of data points processed by algorithms before it ever hits your screen. When the Camp Fire or the Dixie Fire happened, the images we saw weren't just "pictures." They were thermal anomalies detected by sensors orbiting hundreds of miles above us.

The Tech Behind the Glow

Space is crowded. Right now, there are dozens of "eyes" watching California’s dry brush. The big players are the MODIS (Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer) instruments on the Terra and Aqua satellites, and the VIIRS (Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite) on the Suomi NPP and NOAA-20 satellites.

VIIRS is the heavy hitter here. It’s got a higher resolution than the older tech. It can spot a fire that’s relatively small before it turns into a 100,000-acre monster. But here’s the kicker: these satellites aren't just looking for flames. They’re looking for heat. Specifically, they measure "brightness temperature" in the infrared spectrum.

If you look at a raw data feed, you aren't seeing orange flames. You're seeing pixels that represent a specific temperature threshold. When that threshold is crossed, the computer flags it as a "hotspot."

Sometimes the computer is wrong.

🔗 Read more: Apple MagSafe Charger 2m: Is the Extra Length Actually Worth the Price?

I’ve seen "wildfires" on satellite maps that turned out to be the sun reflecting off a large warehouse roof or a particularly hot asphalt parking lot in the Central Valley. This is why ground truth—actual humans in helicopters or on fire lines—is still the gold standard. Satellites give us the "where," but the "what" requires a bit more nuance.

Why California Wildfire Satellite Images Sometimes Lie

Clouds are the enemy. It sounds simple, but if a thick marine layer rolls into Big Sur or a thunderstorm builds over the Sierras, the satellite is essentially blind. It can’t see through the moisture.

Then there's the smoke.

Ironically, the very thing that makes California wildfire satellite images so dramatic—those massive smoke plumes—is exactly what hides the fire's edge from optical sensors. This is where we switch to Short-Wave Infrared (SWIR). SWIR can "pierce" through smoke. When you see those images where the ground looks dark purple but there’s a bright neon red line snaking through it, that’s SWIR at work. It’s a false-color composite. It isn't what your eyes would see if you were standing on the Moon with a telescope. It’s a digital reconstruction designed to save lives by showing exactly where the "head" of the fire is moving.

Real-Time Isn't Always Real-Time

People get frustrated. They refresh the fire map and see the same dots from six hours ago while they can see flames from their backyard.

Satellites move.

💡 You might also like: Dyson V8 Absolute Explained: Why People Still Buy This "Old" Vacuum in 2026

The polar-orbiting ones (like VIIRS) only pass over California a few times a day. You get a snapshot, then you wait. For constant monitoring, we use GOES-West (Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite). It stays fixed over one spot. The trade-off? Resolution. It’s like the difference between a high-def portrait and a grainy security camera feed. GOES is great for seeing the start of a fire—it can detect a heat signature every few minutes—but it won't show you which side of the street the fire is on.

The 2026 Perspective: New Eyes in the Sky

We are getting better at this. The launch of more "SmallSats" and cubesats means the gaps between satellite passes are shrinking. Companies like Planet and Maxar provide high-resolution imagery that can see individual trees. During the 2021 fire season, this data was vital for insurance companies and recovery teams to assess damage without sending people into dangerous, smoldering ruins.

But data costs money.

While NASA and NOAA data is free to the public, the really crisp, "see-the-burnt-mailbox" images usually live behind a paywall. For the average resident in Santa Rosa or Malibu, the free tools like NASA Worldview or the Sentinel Hub Playground are the best bets for DIY monitoring.

How to Actually Use This Data Without Panicking

If you’re looking at satellite imagery during an active fire, stop looking at the red dots in isolation. Red dots (hotspots) can stay on a map for days after the fire has passed because the ground is still hot. Look for the "Latest Acquisition" timestamp. If the data is more than 6 hours old, it’s ancient history in fire time.

Also, pay attention to the wind vectors. A fire doesn't move in a circle; it follows the fuel and the wind. By overlaying wind data from sources like Windy.com onto your California wildfire satellite images, you can see where the smoke—and the embers—are likely to head next.

📖 Related: Uncle Bob Clean Architecture: Why Your Project Is Probably a Mess (And How to Fix It)

Beyond the Burn: The Aftermath

The utility of these images doesn't end when the rain starts. In fact, that's when they become even more critical for a different reason: debris flows.

Burn scars are hydrophobic. The soil literally repels water because of the intense heat of the fire. Satellite imagery using "Normalized Burn Ratio" (NBR) helps geologists predict which hillsides are going to turn into mudslides when the winter atmospheric rivers hit. They compare the "near-infrared" (which healthy plants reflect) to the "short-wave infrared" (which charred earth reflects).

The bigger the difference, the more dangerous the scar.

Actionable Steps for Navigating Fire Imagery

Don't just rely on a screenshot you saw on Facebook. If you want to be an informed observer or if you're living in a high-risk zone, use these specific tools:

- NASA FIRMS (Fire Information for Resource Management System): This is the "pro" tool that's still accessible to the public. You can toggle between VIIRS and MODIS data. Use the "Time" slider to see how the fire has progressed over the last 24 to 48 hours.

- Sentinel Hub: Use this for "False Color" images. If you want to see through the smoke to find the active fire front, select the "Atmospheric Penetration" preset.

- CalTopo: This is a favorite for hikers and SAR teams. It allows you to overlay satellite fire activity on top of highly detailed topographic maps. It’s much more useful for understanding terrain-driven fire behavior.

- Check the "Latency": Always check when the satellite last passed over. If the "Pass Time" was 2:00 AM and it's now 4:00 PM, that map is essentially a ghost of where the fire used to be.

The reality of living in the West is that fire is part of the landscape. These images are our best way to respect the scale of that reality. They provide a perspective that is impossible to get from the ground—a way to see the "beast" in its entirety. Just remember that every pixel on that screen represents a massive amount of energy, and often, a massive amount of loss.

Understanding the limitations of the technology—the "cloud gaps," the "sensor noise," and the "revisit times"—makes you more than just a spectator. It makes you a more prepared citizen. Stay updated by checking the official NOAA NESDIS feeds for the most vetted, processed data available during the peak of the season. Use the tools, but always listen to local evacuation orders first; a satellite can see the heat, but it can't see the traffic jam on the only road out of town.