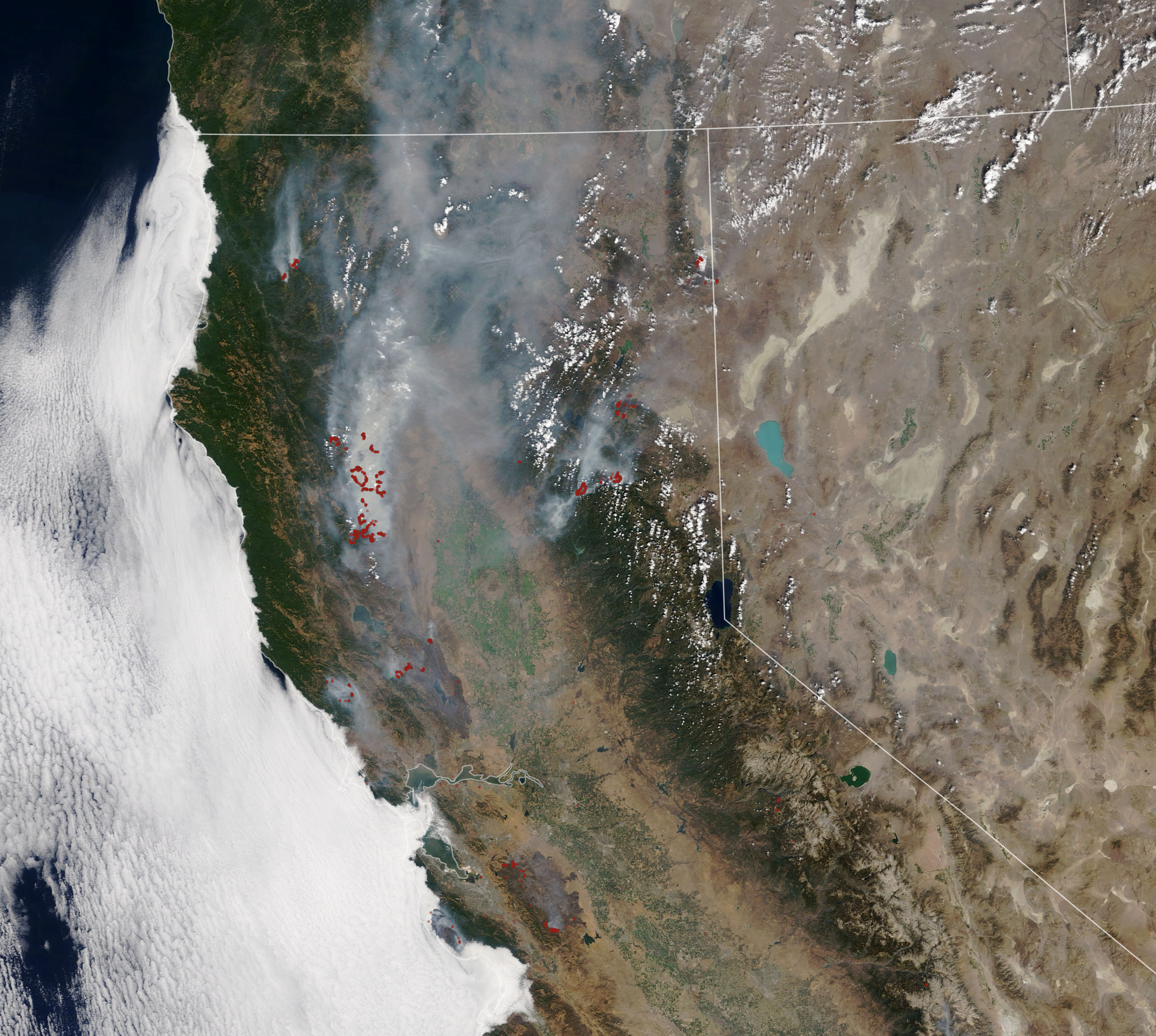

Seeing a California wildfire satellite image for the first time is jarring. It’s weirdly beautiful in a way that feels wrong. You see these massive, swirling plumes of ochre and gray drifting across the Pacific, while tiny, bright red dots—what scientists call "hotspots"—mark where the land is literally being consumed. It looks like a painting. But it’s data. Real, high-stakes data that tells us if a town is about to be erased or if the wind is finally shifting in our favor.

People search for these images during every fire season because they want the truth. They want to see what’s happening without the filter of a news desk. Honestly, though, if you don't know what you're looking at, you might misinterpret everything. Those "fire" pixels you see on a public dashboard? They aren't actually photos of flames.

Why Your California Wildfire Satellite Image Looks Different on Different Sites

You’ve probably noticed that a California wildfire satellite image on NASA’s Worldview looks nothing like what you see on a local news station or a specialized tool like Watch Duty. There’s a reason for that. Satellites don’t just take "pictures" like your iPhone. They capture different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum.

Most of what we see is "True Color." This is basically what an astronaut would see looking out a window. It’s great for seeing smoke. Smoke is the big tell. It tells you the direction of the transport winds and how intense the combustion is. If the smoke is white, it’s often lots of water vapor or lighter fuels burning. If it’s thick, dark brown, or black, that’s a "dirty" burn—heavy timber or structures are going up.

But true color is useless at night. And it’s useless if the smoke is so thick you can't see the ground.

That’s where Short-Wave Infrared (SWIR) comes in. SWIR can "see" through smoke. When you see those neon orange or red overlays on a map, you’re looking at infrared data. These sensors, like the ones on the VIIRS (Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite) instrument aboard the Suomi NPP satellite, pick up heat signatures. They’re detecting the thermal radiation coming off the ground.

The Problem With Resolution

Not all satellites are created equal. This is the part that trips people up. You have two main types: Geostationary and Polar-orbiting.

👉 See also: How Far We’ve Come: Why the Future of Tech is Faster (and Weirder) Than You Think

GOES-West is the big one for California. It sits in a fixed spot way out in space. Because it stays in one place, it gives us a fresh California wildfire satellite image every few minutes. That’s incredible for tracking how fast a fire is moving in real-time. The downside? The resolution is kinda low. One pixel might cover a couple of kilometers. It's "blurry" but fast.

Then you have the polar-orbiters like Landsat 8 or 9. These are much closer to Earth. The detail is insane. You can see individual streets or even specific houses that have been spared. But they only pass over the same spot every few days. If a fire starts on a Monday, a Landsat image might not be available until Thursday. By then, the situation has totally changed.

Reading Between the Pixels: Misconceptions About Hotspots

Let's talk about those red dots. If you go to a site like FIRMS (Fire Information for Resource Management System), you’ll see a California wildfire satellite image peppered with little squares.

A lot of people think: That square is exactly where the fire is. Not quite.

A "hotspot" represents the center of a pixel where the satellite detected a significant temperature anomaly. It doesn't mean the entire 375-meter square is a wall of flames. It could be one very hot chimney or a small patch of burning brush that triggered the sensor. Conversely, a fire might be burning under a thick canopy of old-growth trees, and the satellite might miss it entirely because the heat is shielded by the leaves.

The Heat Delay

There is also a temporal lag. By the time that California wildfire satellite image hits your screen, it's often 30 minutes to 3 hours old. In a wind-driven event like the 2018 Camp Fire or the more recent Park Fire, three hours is an eternity. A fire can jump miles in that time. Relying solely on satellite pixels for evacuation is a bad move. You have to use them in tandem with ground-based reports and the "hazard" layers provided by CAL FIRE.

The Tech Behind the Smoke

We are currently in a bit of a golden age for this technology. It's not just NASA anymore. Private companies like Planet and Maxar are getting involved. They have "constellations" of hundreds of tiny satellites (CubeSats) that can provide a high-resolution California wildfire satellite image almost daily.

They use something called "Synthetic Aperture Radar" (SAR) too. This is wild stuff. SAR doesn't care about clouds. It doesn't care about smoke. It doesn't even care about light. It bounces microwave signals off the ground to map the texture of the terrain. After a fire, SAR is used to determine how much vegetation was lost—what we call "burn severity."

Burn Scars and Mudslides

A California wildfire satellite image taken weeks after the flames are out is arguably just as important as the ones taken during the heat. These images show "burn scars." To the naked eye, it’s just black earth. But using the Normalized Burn Ratio (NBR)—a calculation comparing near-infrared and shortwave infrared light—scientists can see how badly the soil was "cooked."

If the soil becomes hydrophobic (water-repellent) because the heat was so intense, the next big rain is going to cause a massive debris flow. We saw this in Montecito. The satellite data told the story before the rain even fell. It showed exactly where the mountain was most vulnerable.

How to Find the Most Accurate Data Right Now

If you are trying to track a fire near you, don't just Google "California wildfire satellite image" and click on the first grainy photo you see on Twitter. Most of those are reposts of old data.

Go to the source.

- NASA FIRMS: This is the gold standard for raw thermal data. You can toggle between VIIRS and MODIS satellites. Use the "Time" slider to see how the fire has progressed over the last 24 hours.

- College of DuPage - Nexlab: This is where the weather nerds go. It gives you direct access to GOES-West imagery. You can watch the "Fire Temperature" loop, which looks like a black-and-white movie where the fire glows neon blue or white.

- Watch Duty: If you want a California wildfire satellite image that is actually interpreted by humans, this app is the best. They combine satellite hits with radio traffic and official government maps.

- Sentinel Hub: This is for the power users. It lets you apply different "scripts" to satellite data. You can turn on a "False Color" filter that makes healthy vegetation look bright red and burnt areas look dark green. It’s confusing at first, but it makes the fire perimeter pop with incredible clarity.

The Human Element in a Digital View

It’s easy to get lost in the data. You zoom in on a California wildfire satellite image and see a heat hit near a ridge you know. It feels clinical. But every one of those pixels represents someone's backyard, a forest that’s been there for centuries, or a crew of firefighters on the ground breathing in that smoke.

Satellites are essentially our "eyes in the sky," but they have limitations. They can be "blinded" by thick pyrocumulus clouds—those massive, white thunderclouds that fires create themselves. When a fire gets big enough to create its own weather, the satellite often can't see the ground at all. It just sees the top of the cloud. This is when ground-based IR flights (planes with heat sensors) take over. They fly under the clouds at night to get the "true" line of the fire.

What to Look for Next

The next leap in this field is AI-integrated detection. Companies like Pano AI are combining satellite imagery with mountain-top cameras. The AI scans the California wildfire satellite image for heat and cross-references it with the cameras to see if there's a smoke column. This can cut response times from hours to minutes.

Instead of waiting for a 911 call, the satellite sees the "birth" of the fire from space.

Actionable Steps for Using Satellite Maps

If you live in a fire-prone area, or you're just a data enthusiast, here is how you should actually use a California wildfire satellite image:

- Check the Timestamp: Always look for the "acquisition time." If the image is more than 6 hours old, the "active" fire line has likely moved.

- Ignore the "Glow": In long-exposure or certain infrared views, the fire looks much larger than it is because of "blooming." This is when the sensor is overwhelmed by intense heat, making the pixel look like it's bleeding into its neighbors.

- Compare True Color vs. IR: Use true color to see where the smoke is going (for air quality) and use IR to see where the heat is (for safety).

- Watch the Wind: If the smoke plumes in the satellite image are suddenly changing direction or laying flat against the ground, the wind is picking up. This is usually when fires become most dangerous.

- Verify with "Ground Truth": Never use a satellite image as your only source of truth. Check local Sheriff's offices or CAL FIRE's official incident pages to confirm what the "blobs" are actually doing.

The technology is getting better every single year. We are seeing things now that were impossible a decade ago. But remember, a California wildfire satellite image is just one tool in the kit. It's a snapshot of a moment in time, captured from hundreds of miles up, reflecting a reality that is moving much faster than a satellite can orbit.

Pro-Tip: If you're using NASA's FIRMS, look for "Day/Night Band" imagery. It's essentially a "low light" camera that can see the actual glow of the fire at night, separate from the heat signature. It’s the closest thing to a real photo of the disaster from space.

Stay Prepared: Download the Watch Duty app and bookmark the NASA FIRMS Fire Map. Familiarize yourself with the "MODIS" and "VIIRS" layers now, before there is smoke in the air, so you aren't trying to learn a complex GIS interface during an emergency. Knowing how to read a California wildfire satellite image today could save you hours of panic tomorrow.