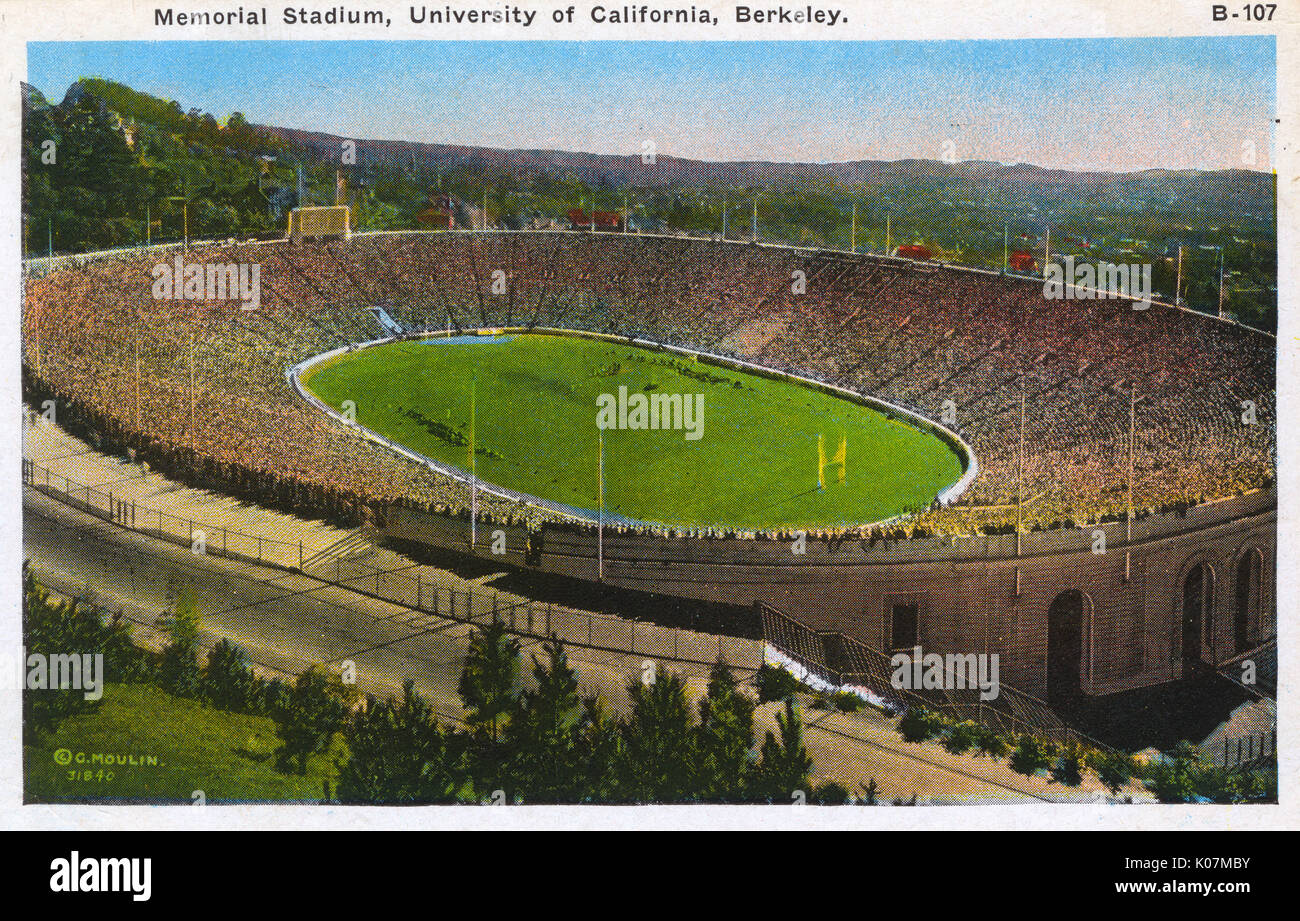

You’re standing on the 50-yard line at California Memorial Stadium. It feels solid. The turf is crisp, the air smells like the Bay, and the view of the Campanile is iconic. But honestly? You’re standing on a ticking time bomb. Literally.

The University of California Berkeley stadium isn't just a place where the Golden Bears play football; it’s a massive civil engineering experiment sitting directly on top of the Hayward Fault. If you look closely at the outer walls on the north and south ends, you can actually see where the earth is slowly, relentlessly tearing the stadium in two. This isn't some metaphor for a rivalry game. It’s active plate tectonics.

For nearly a century, this stadium has been the heart of Berkeley sports, surviving everything from the Great Depression to a massive 2012 renovation that cost nearly half a billion dollars. It’s a temple of college football history, but it’s also one of the weirdest, most precarious pieces of architecture in the United States.

The Fault Line Running Through Section NN

Most people come here for the atmosphere. They want to see the Tightwad Hill crowd—the fans who sit for free on the hillside overlooking the field—and they want to hear the Straw Hat Band. But the real story is under your feet.

The Hayward Fault is one of the most dangerous faults in the world. It runs lengthwise through the stadium, entering at the south frame and exiting through the north. Because the fault is "creeping," the two halves of the stadium are moving in opposite directions at a rate of about five millimeters per year.

That doesn't sound like much. Until you realize that since the stadium opened in 1923, the walls have shifted by more than a foot.

Engineers have had to get creative. During the massive $321 million renovation completed in 2012, they didn't just "fix" the stadium. They basically turned it into a series of floating blocks. The sections sitting directly on the fault line are designed to slide independently of the rest of the structure. If the "Big One" hits, the stadium is meant to break in a controlled way, hopefully keeping the 63,000 people inside safe while the earth moves beneath them.

It’s a bizarre reality. You’re cheering for a touchdown while the Pacific and North American plates are quietly engaged in a multi-million-year tug-of-war.

A Design Inspired by the Roman Colosseum

The University of California Berkeley stadium was dedicated in 1923 to the students and alumni who died in World War I. John Galen Howard, the university’s legendary campus architect, wanted something that felt eternal. He looked at the Roman Colosseum and thought, Yeah, let’s do that, but on a hill.

👉 See also: Tottenham vs FC Barcelona: Why This Matchup Still Matters in 2026

The stadium is a "bowl" style, but only on one side. The east side is literally carved into the side of Charter Hill. This gives it that intimate, vertical feel that makes it one of the louder venues in the Pac-12 (or whatever the conference landscape looks like by the time you read this).

The Aesthetic vs. The Reality

Walking through the gates, you see the beautiful neoclassical granite. It feels heavy. It feels permanent. But that weight was part of the problem. For decades, the stadium was a "non-ductile" concrete mess. In a major quake, those pretty walls would have just crumbled.

The 2012 overhaul was controversial. Critics pointed to the massive debt the university took on—debt they are still paying off—to fund a luxury club level and modern locker rooms. But the university argued it was a matter of life or death. You couldn't just leave a 60,000-seat stadium sitting on a fault line without seismic retrofitting.

- Capacity: Originally 73,000+; now roughly 62,469.

- The Surface: They switched from grass to Matrix Turf, which handles the Berkeley rain much better.

- The Views: It is arguably the only stadium in America where you can see the Golden Gate Bridge from your seat.

The Tightwad Hill Tradition

You can't talk about California Memorial Stadium without mentioning the cheapskates. And I say that with love.

Tightwad Hill is a Berkeley institution. It’s the steep, tree-covered slope of Charter Hill that looks directly into the bowl. Since the stadium’s inception, fans (mostly students and eccentric locals) have hiked up there to watch the game for free.

The university has tried to block the view multiple times. They’ve planted trees. They’ve put up fences. The "Tightwads" just bring ladders or find new gaps in the foliage. It represents the quintessential Berkeley spirit: a mix of devotion to the team and a stubborn refusal to pay $80 for a ticket.

Honestly, the view from the hill is better than half the seats in the end zone. You get the whole panorama—the game, the campus, and the sunset over the San Francisco Bay.

Why the 2012 Renovation Still Sparks Debate

The University of California Berkeley stadium renovation wasn't just about football. It was a massive financial gamble. The school created the "Endowment Seating Program," asking wealthy donors to pay huge sums for long-term rights to the best seats.

✨ Don't miss: Buddy Hield Sacramento Kings: What Really Happened Behind the Scenes

The goal? Pay off the $445 million in construction costs.

The reality? It’s been a struggle. Between coaching changes, shifting conference alignments, and the general volatility of college sports, the revenue hasn't always matched the projections. Some faculty members are still salty about it. They argue that the money could have gone to research or housing.

But talk to a player or a die-hard alum, and they’ll tell you the old stadium was a dump. The plumbing failed. The locker rooms were cramped. The seismic risk was a PR nightmare. Now, they have the Simpson Center for Student-Athlete Excellence, a high-tech facility tucked under the west side of the stadium that rivals anything in the NFL.

The 1982 "The Play" and the Ghost of Kevin Moen

If you walk through the North Tunnel, you’re walking the same path as the most famous moment in college football history.

November 20, 1982. The Big Game against Stanford.

You know the story. Four laterals. The Stanford band already on the field because they thought the game was over. Kevin Moen plowing through a trombone player in the end zone.

That happened here.

The stadium is haunted by that moment. There’s a spot in the end zone where it all culminated. It’s the reason why, to this day, Stanford fans get twitchy when they see a trombone, and Cal fans never, ever leave a game early.

🔗 Read more: Why the March Madness 2022 Bracket Still Haunts Your Sports Betting Group Chat

Survival Tips for Your Visit

If you're heading to the University of California Berkeley stadium, don't just show up and expect a standard pro-sports experience. Berkeley is different.

First, don't drive. Just don't. Parking in the Berkeley hills is a nightmare involving steep grades and aggressive meter maids. Take BART to the Downtown Berkeley station and walk up through campus. It’s a mile-long hike, but you get to pass the Sproul Plaza and the Sather Gate.

Second, layer up. The stadium is in a microclimate. It might be 75 degrees in the sun during the first quarter, but as soon as the fog rolls over the Berkeley hills in the fourth quarter, the temperature drops 20 degrees. You'll see freshmen in shorts shivering while the "old-timers" are wearing heavy wool Cal sweaters. Listen to the old-timers.

Third, check out the fault creep. Before you go in, walk to the base of the stadium walls on the exterior. Look for the cracks that have been patched and re-patched. It’s a humbling reminder that nature always wins.

The Architectural Nuance Nobody Notices

Most people focus on the field, but the "outer skin" of the stadium is a marvel. During the 2012 project, they had to preserve the historic facade because the stadium is on the National Register of Historic Places.

They basically hollowed out the stadium like a pumpkin. They kept the historic outer shell, built a brand-new, seismically safe stadium inside it, and then tied the two together. It’s one of the most complex "facadectomies" ever performed on a sports venue.

When you sit in the new West Side stands, you’re actually on a massive steel structure that is separate from the historic concrete. This allows the new sections to vibrate at a different frequency than the old walls during an earthquake. It’s brilliant engineering that most fans completely ignore while they’re yelling at the refs.

What’s Next for Memorial Stadium?

The future of the University of California Berkeley stadium is tied to the survival of the Cal athletic department in a rapidly changing NCAA. As the school moves into the ACC—a move that still feels weird to everyone in the Bay Area—the stadium will host teams like Florida State and Clemson.

The travel costs are insane. The revenue gaps are real. But the stadium remains the university's greatest physical asset. It’s a recruitment tool, a community hub, and a monument to Berkeley's resilience.

Whether you're a geology nerd, a football fanatic, or just someone who likes a good view, this stadium demands respect. It’s survived a century of physical shifts and cultural changes. It’s cracked, it’s expensive, and it’s sitting on a fault, but it’s still the best place in the world to watch a game on a Saturday afternoon.

Actionable Steps for Your Visit

- Spot the Fault: Before entering, walk to the exterior of the South Gate. Look for the vertical cracks in the concrete—this is where the Hayward Fault enters the building.

- Hike Tightwad Hill: Even if you have a ticket, take 10 minutes to hike the trail behind the stadium. The photo op of the stadium with the San Francisco skyline in the background is unbeatable.

- Visit the Hall of Fame: Located inside the Simpson Center, it holds the history of Cal athletics, including artifacts from the 1982 "The Play."

- Check the Schedule for Non-Game Events: The stadium often hosts sunrise yoga or community walks. It's the best way to see the architecture without the 60,000-person crowd.

- Layer Your Clothing: Berkeley weather is notoriously fickle; bring a windbreaker even if the sun is out at kickoff.