It’s the flute solo. That’s usually the first thing that hits you—that weirdly perfect, slightly mournful alto flute bridge that doesn't really belong in a pop song but somehow defines the whole track. Most people hear California Dreamin’ by The Mamas and the Papas and immediately think of sun-drenched beaches and 1960s flower power. It’s the ultimate postcard for the West Coast. But here's the thing: the song wasn't written in California. It wasn't even written during a "good" time. It was written in a cold, dingy hotel room in New York City during one of the harshest winters on record.

John Phillips and Michelle Phillips were broke. They were staying at the Albert Hotel in Greenwich Village, and Michelle, a California native, was absolutely miserable in the New York slush. She was homesick. She missed the light. John woke her up in the middle of the night to help him finish a song he’d started after a walk to St. Patrick’s Cathedral. That’s the real origin of that "brown leaves" and "gray sky" imagery. It’s not a celebration of California; it’s a desperate, shivering prayer to get back there.

The Song That Almost Wasn't Theirs

You might think The Mamas and the Papas just walked into a studio and knocked out a hit. Not even close. Before their version became the definitive anthem of a generation, the song was actually recorded by Barry McGuire—the guy famous for "Eve of Destruction."

The Mamas and the Papas were actually singing backup on his version. If you listen closely to the McGuire track, you can hear the exact same arrangement. Lou Adler, the producer, realized halfway through that the backing vocalists actually sounded better than the lead. He literally wiped McGuire’s lead vocal (mostly) and had Denny Doherty re-record the melody. If you listen to the hit version today on a good pair of headphones, you can still faintly hear McGuire’s gravelly voice in the background because they couldn't totally bleed it out of the master tape. It’s a ghost in the machine.

Honestly, the vocal layering is what makes it. It’s a harmonic masterclass. Most 1965 pop songs were pretty straightforward. This was different. It used a technique called "counterpoint," where different voices move independently. When Denny sings "All the leaves are brown," and the others echo him, it’s not just a repeat; it’s a texture. It creates this wall of sound that feels both massive and intimate.

That Flute Solo Was a Happy Accident

Bud Shank. Remember that name. He was a jazz musician who happened to be in the studio. In the mid-sixties, rock songs didn't usually have flute solos; they had guitar solos or maybe a cheesy organ riff. But Lou Adler wanted something "sophisticated."

🔗 Read more: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

Shank walked in, listened to the track once, and improvised that solo. He didn't have a chart. He didn't have a plan. He just played what he felt. That alto flute gave the song a "cool jazz" edge that separated it from the bubblegum pop of the era. It added a layer of sophistication that made the song acceptable to adults while the kids were busy buying the 45 RPM records. It's essentially why the song has never aged. It doesn't sound like 1965; it sounds like a mood.

The Religious Undercurrent and the "Preacher"

One of the weirdest parts of California Dreamin’ by The Mamas and the Papas is the second verse. "Stopped into a church I passed along the way." People debate this all the time. Was it about a real church? Yeah, it was St. Patrick's. John Phillips actually liked the atmosphere of old churches, even if he wasn't particularly devout at the time.

The line "Well, I got down on my knees and I began to pray" is followed by the preacher liking the cold. It’s a cynical little nod. The preacher knows that if it stays cold, people stay in the church. It adds a bit of grit to the song. It’s not all sunshine and lollipops. There’s a sense of being trapped—physically by the winter and spiritually by the search for something better.

The Technical Wizardry of the 1960s

The recording happened at United Western Recorders in Hollywood. They used a four-track machine. Think about that. Today, a teenager with a laptop has 500 tracks. These guys had four.

- The rhythm section (drums, bass, acoustic guitar).

- The lead vocal.

- The backing harmonies.

- The overdubs (like that flute).

To get that thick, lush sound, they had to "bounce" tracks down, which basically means mixing three tracks onto one to free up space. Every time you do that, you lose a little bit of quality, but it creates a specific "glue" that modern digital recording can't quite replicate. The "hiss" and the warmth of the tape are part of the instrument. P.F. Sloan played the iconic acoustic guitar intro. He used a 12-string, which is why it sounds so jangly and full. It catches the ear immediately. Two bars in, and you know exactly what song it is. That's the hallmark of a masterpiece.

💡 You might also like: Why American Beauty by the Grateful Dead is Still the Gold Standard of Americana

Why It Still Hits in 2026

We live in an era of hyper-perfection. Everything is pitch-corrected. Everything is on a grid. California Dreamin’ by The Mamas and the Papas feels human because it is. You can hear the breath. You can hear the slight imperfections in the vocal blend.

It also taps into a universal feeling: the "elsewhere" syndrome. Everyone has a "California." For the writers, it was a physical place. For us, it might be a better job, a past relationship, or just a state of mind where the sun actually shines. It’s a song about longing. Longing never goes out of style.

Breaking Down the Chart Success

The song didn't explode overnight. It was a "slow burn." It was released in late 1965 but didn't peak until early 1966. It eventually hit #4 on the Billboard Hot 100. It stayed on the charts for 17 weeks. In the 60s, that was an eternity.

- Certified Gold: It sold over a million copies almost immediately.

- The "California" Effect: It’s credited with helping trigger the massive migration of youth to the West Coast in 1967 (the Summer of Love).

- Cover Versions: Everyone from The Beach Boys to José Feliciano to Sia has covered it. None of them capture the specific tension of the original.

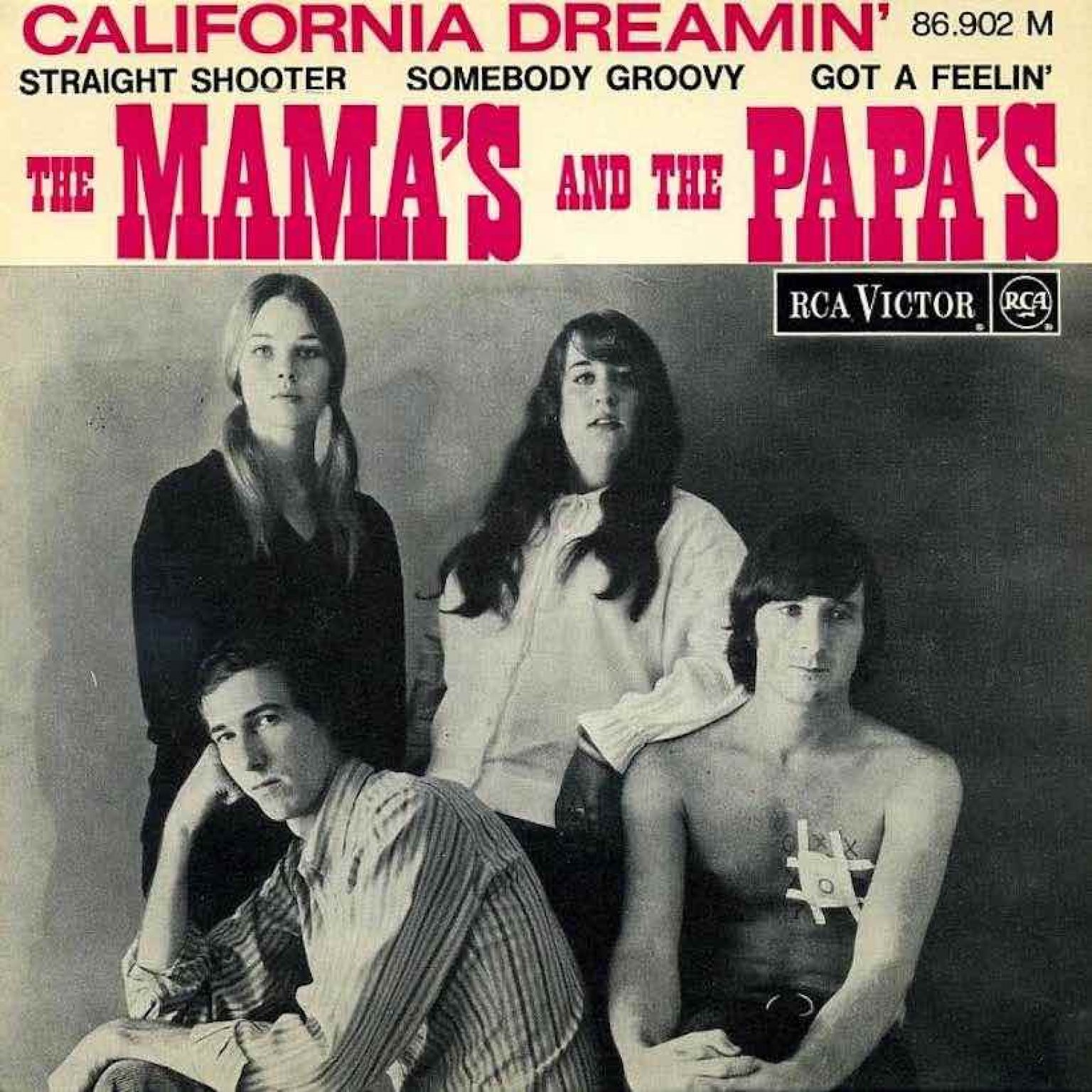

The Beach Boys version is interesting because it’s much more "pro-California," but it loses the shivering New York desperation that John Phillips baked into the original lyrics. Feliciano's version is probably the most soul-stirring, turning it into a slow, acoustic lament. But the Mamas and the Papas version remains the gold standard because of the vocal chemistry between Cass Elliot, Denny Doherty, Michelle Phillips, and John Phillips. Their voices didn't just blend; they vibrated against each other.

How to Truly Appreciate the Track Today

If you want to understand why this song is a pillar of music history, don't just stream it on a tiny phone speaker. You've gotta hear the separation.

📖 Related: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

Find a high-quality mono mix if you can. While stereo was the "new thing" back then, the mono mix is punchier and was what the band actually spent the most time perfecting. The bass (played by the legendary Joe Osborn) drives the song much harder in the mono version. It’s less of a "dream" and more of a "march."

Actionable Insights for Music Lovers:

- Listen for the "Ghost" Vocal: Use high-back headphones and pan to the left during the verses. Try to hear Barry McGuire’s original scratch vocal underneath Denny’s.

- Analyze the Harmony: Try to follow just Mama Cass’s voice throughout the chorus. She often takes the "low" parts that give the song its foundational richness.

- Check Out the Wrecking Crew: Research the session musicians. The song wouldn't exist without Joe Osborn (bass) and Hal Blaine (drums). These were the same guys who played on almost every hit of the era, from the Beach Boys to Simon & Garfunkel.

- The Flute Context: Listen to Bud Shank’s solo, then go listen to a standard 1965 pop song like "I'm a Believer." The difference in musical complexity is staggering.

The song serves as a reminder that great art often comes from discomfort. If John and Michelle had been warm and happy in LA, they never would have written their greatest hit. They needed the gray sky and the brown leaves to find the dream.

Next time you hear those opening chords, remember the Albert Hotel. Remember the cold. It makes the "warmth" of the chorus feel a lot more earned.