You're sitting there, staring at a limit problem that looks like a bowl of alphabet soup, and your brain just freezes. It’s a classic. Most people think they just need to memorize a calculus ab formula sheet and they’ll magically coast to a 5 on the AP exam. Honestly? That’s the quickest way to end up with a 2.

The College Board doesn't actually give you a formula sheet for the AP Calculus AB exam. Yeah, you read that right. Unlike the physics or chemistry tests where they hand you a nice little packet of equations, calculus expects you to carry the entire library in your skull. It’s brutal, but it's the reality of how the test is built. You’ve gotta know your derivatives, your integrals, and those pesky theorems by heart because the second you hesitate, you’re losing precious seconds on the multiple-choice section.

Why a Calculus AB Formula Sheet is Basically Your Survival Map

Think of the formulas as the grammar of a language. If you don't know the words, you can't write the essay. But just knowing the words doesn't mean you can write a masterpiece. You need to understand the why behind them.

Take the Power Rule. It’s the first thing everyone learns. You see $x^n$ and you immediately think $nx^{n-1}$. Easy. But then the exam throws a curveball like $\frac{d}{dx}(\pi^3)$. Half the students in the room will write $3\pi^2$ because they’re on autopilot. They forget that $\pi$ is a constant. The derivative is zero. This is where "memorizing" fails and "understanding" saves your grade.

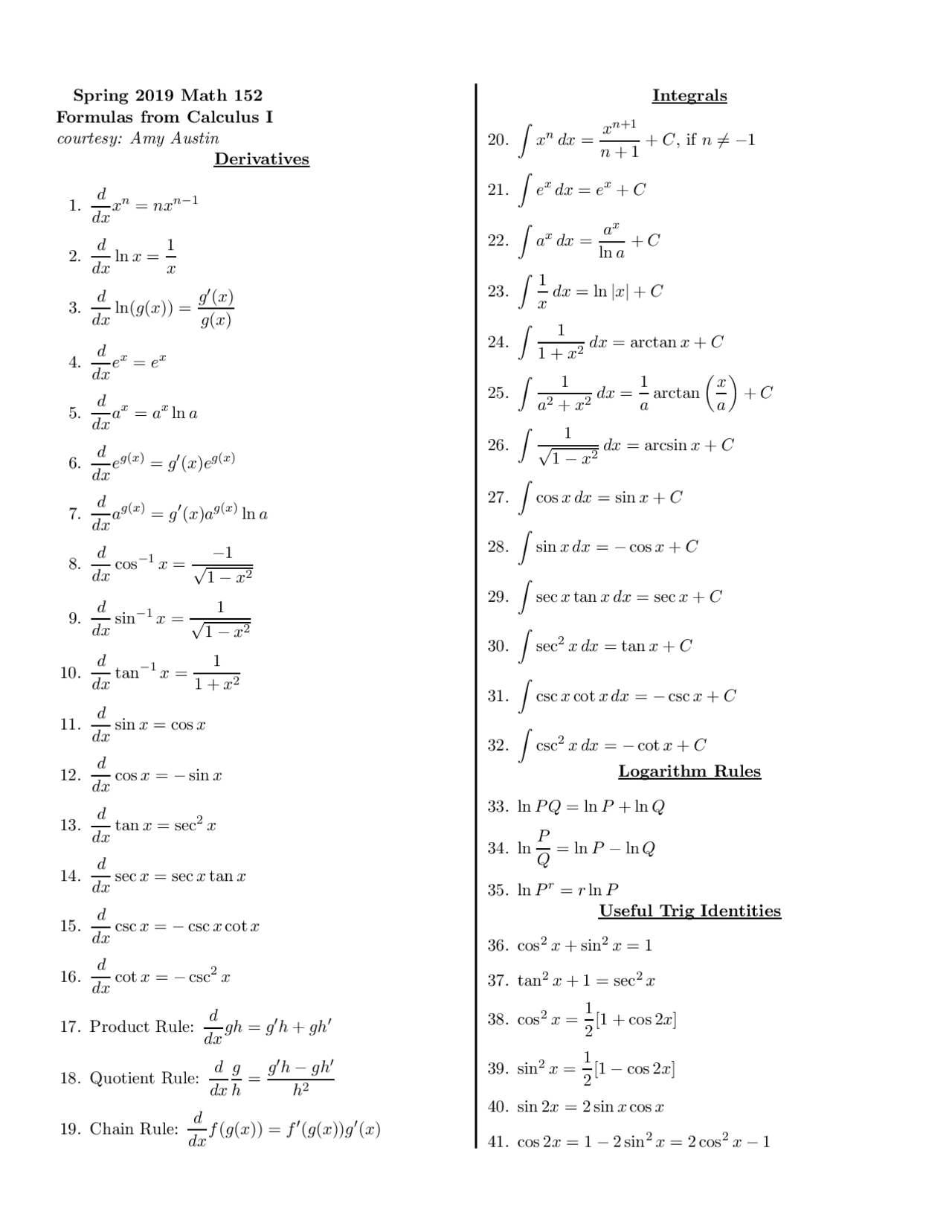

Most successful students create their own calculus ab formula sheet early in the year and add to it as they go. It becomes a living document. You start with limits, move to derivatives, then hit the "Big Three" theorems: Intermediate Value Theorem (IVT), Mean Value Theorem (MVT), and Extreme Value Theorem (EVT). If you can't distinguish between these three at a glance, you're going to have a rough time on the FRQs (Free Response Questions).

The Limits that Actually Matter

Limits are the foundation, but let's be real—on the actual exam, most limit questions are just L'Hôpital's Rule in disguise.

If you plug in a number and get $0/0$ or $\infty/\infty$, you don't just give up. You take the derivative of the top and the derivative of the bottom. It’s like a cheat code. But here’s the kicker: the College Board is picky. On the FRQ, if you don’t explicitly state that the limit of the numerator and the limit of the denominator are both zero, they’ll snatch those points right back.

Then there's the definition of a derivative. It’s that long, ugly limit:

$$\lim_{h \to 0} \frac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{h}$$

You’ll see a question that looks like a terrifying limit calculation, but if you recognize the structure, you realize they’re just asking you to find $f'(x)$ for a specific function. Recognizing that pattern is faster than actually doing the algebra.

Derivatives You Can't Afford to Forget

The "big" ones are the ones people stumble on during the final hour. We all know the derivative of $\sin(x)$ is $\cos(x)$. That’s easy. But what about $\sec(x)$? Or $\tan(x)$?

- $\frac{d}{dx} \tan(x) = \sec^2(x)$

- $\frac{d}{dx} \sec(x) = \sec(x)\tan(x)$

- $\frac{d}{dx} a^x = a^x \ln(a)$

That last one, the exponential rule for bases other than $e$, is a frequent "trap" question. If you see $3^x$ and write $x \cdot 3^{x-1}$, you’ve fallen for it.

And don't even get me started on the Chain Rule. It’s the single most important tool in your arsenal. Every year, thousands of students lose points because they forgot to multiply by the "inside" derivative. It’s the "onion" method—peel back the layers one by one. If you have $\sin(x^2)$, the derivative isn't just $\cos(x^2)$. It’s $2x \cos(x^2)$. Forget that $2x$ and your entire problem falls apart like a house of cards.

The Theorems: The "Law" of Calculus

The Mean Value Theorem (MVT) is basically the "speeding ticket" theorem. If you drove 100 miles in two hours, at some point, you were going exactly 50 mph. Mathematically, it says if a function is continuous and differentiable, there’s a point $c$ where $f'(c) = \frac{f(b)-f(a)}{b-a}$.

The College Board loves to ask "Is there a time $t$ where the acceleration is...?" or "Must there be a value where...?" When you see the word must, your brain should immediately scream "THOREM!" You have to check the conditions first, though. If the function isn't differentiable, MVT is useless. It’s like trying to use a coupon that’s already expired.

Integration: Doing It All Backwards

Integration is where the calculus ab formula sheet gets really dense. You’ve got the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus (FTC), which is the bridge between derivatives and integrals.

🔗 Read more: What Are Discriminants in Math and Why They Actually Save You Time

$$\int_{a}^{b} f'(x) dx = f(b) - f(a)$$

This looks simple, but the AP exam uses it in "graphical" ways. They’ll give you a graph of $f'$ and ask for the value of $f(5)$ given $f(0)=2$. You have to realize that the area under the curve is the change in value.

Then there's $u$-substitution. It’s the reverse Chain Rule. If the derivative of the "inside" is sitting right there next to it, you’re golden. But if it’s not? You might have to get creative with some algebra.

Area and Volume: The Geometry of Calculus

This is usually the last unit, and it’s where everyone starts to smell the finish line and gets lazy. Disk method, washer method, and cross-sections.

- Disk Method: $V = \pi \int [R(x)]^2 dx$

- Washer Method: $V = \pi \int ([R(x)]^2 - [r(x)]^2) dx$

- Cross-sections: $V = \int A(x) dx$

People always forget the $\pi$ in the disk and washer methods. Always. It’s such a small thing, but it turns a perfect answer into a wrong one. And remember, the washer method is "Outer squared minus Inner squared," NOT "Outer minus Inner, all squared." That’s a massive distinction that changes the math completely.

Common Pitfalls and How to Dodge Them

One of the weirdest things about Calculus AB is the "+ C." You’d think by May, everyone would remember to add the constant of integration on indefinite integrals. Nope. It’s the number one reason students lose a point on the easier questions.

Another big one? Misinterpreting the "Average Value" of a function.

The average value is $\frac{1}{b-a} \int_{a}^{b} f(x) dx$.

Students often confuse this with the average rate of change, which is just the slope formula from algebra: $\frac{f(b)-f(a)}{b-a}$. One involves an integral; the other is just subtraction and division. If the question asks for the average temperature and gives you a function for temperature, use the integral. If it asks for the average rate of temperature change, use the slope.

Calculator vs. No Calculator

The exam is split. Sometimes you have your TI-84 (or whatever you use), and sometimes you only have your pencil. On the calculator section, don't try to be a hero. If you need to find an integral, use fnInt. If you need a derivative at a point, use nDeriv. The College Board doesn't give extra points for doing it by hand when you have a calculator in your lap. They just want the answer (rounded to three decimal places—always three!).

Building Your Own "Cheat Sheet" for Practice

Since you can't take a sheet into the room, you need to build one in your head through repetition. Start by writing down these categories:

- Limits: L'Hôpital's, Continuity rules, Squeeze Theorem.

- Derivatives: Trig, Inverse Trig (especially $\arctan$), Chain Rule, Product/Quotient Rules.

- Theorems: IVT, EVT, MVT, and the second derivative test for extrema.

- Integrals: Power rule, $1/x \to \ln|x|$, $e^x$, $u$-sub.

- Applications: Related rates (the "ladder" or "balloon" problems), Optimization, Area/Volume.

Final Prep: The Week Before

Don't spend the night before the exam trying to learn the washer method for the first time. It won't stick. Instead, focus on the "small" things that are easy to forget. Re-memorize the derivative of $\ln(u)$ and the integral of $\sec^2(x)$.

Practice writing out the justifications for the theorems. Use the exact phrasing: "Since $f(x)$ is continuous on $[a,b]$ and differentiable on $(a,b)$..." It feels like overkill, but that’s what the graders are looking for. They have a rubric, and they want to check those boxes.

Calculus AB isn't about being a math genius. It’s about being a pattern recognition expert. The formulas are your patterns. If you see "rate of change," think derivative. If you see "total amount" or "accumulation," think integral. If you see "concavity," think second derivative.

Next Steps for Your Study Session:

Grab a blank sheet of paper right now. Try to write down every derivative and integral formula you can remember without looking at your notes. Once you hit a wall, open your textbook and fill in the gaps with a red pen. Those red marks are exactly what you need to focus on for the next 48 hours. Focus specifically on the Trig derivatives and the FTC Part 2—those are the high-yield areas that separate the 3s from the 5s. After you've mastered the list, take a past FRQ from the College Board website and try to solve it using only the "mental sheet" you've just built.