Money has a weird relationship with time. If someone offered you $10,000 today or $10,000 spread out over the next ten years, you’d take the lump sum immediately. Why? Because a dollar today is objectively worth more than a dollar tomorrow. This isn't just a hunch; it’s the bedrock of finance. When we talk about calculating the present value of an annuity, we are basically trying to figure out what a stream of future payments is worth in "today’s money." Whether you’re looking at a lottery payout, a pension plan, or a structured settlement, knowing this number stops you from getting ripped off.

Honestly, it’s about the "opportunity cost." If you have the cash now, you can invest it. You can put it in an index fund, buy a rental property, or even stick it in a high-yield savings account. Future money just sits there in the ether, losing value to inflation while you wait for it to arrive.

The actual math behind the curtain

Don't let the word "annuity" scare you. It’s just a series of equal payments made at regular intervals. Think of your Netflix subscription as an annuity you pay, or a retirement distribution as one you receive.

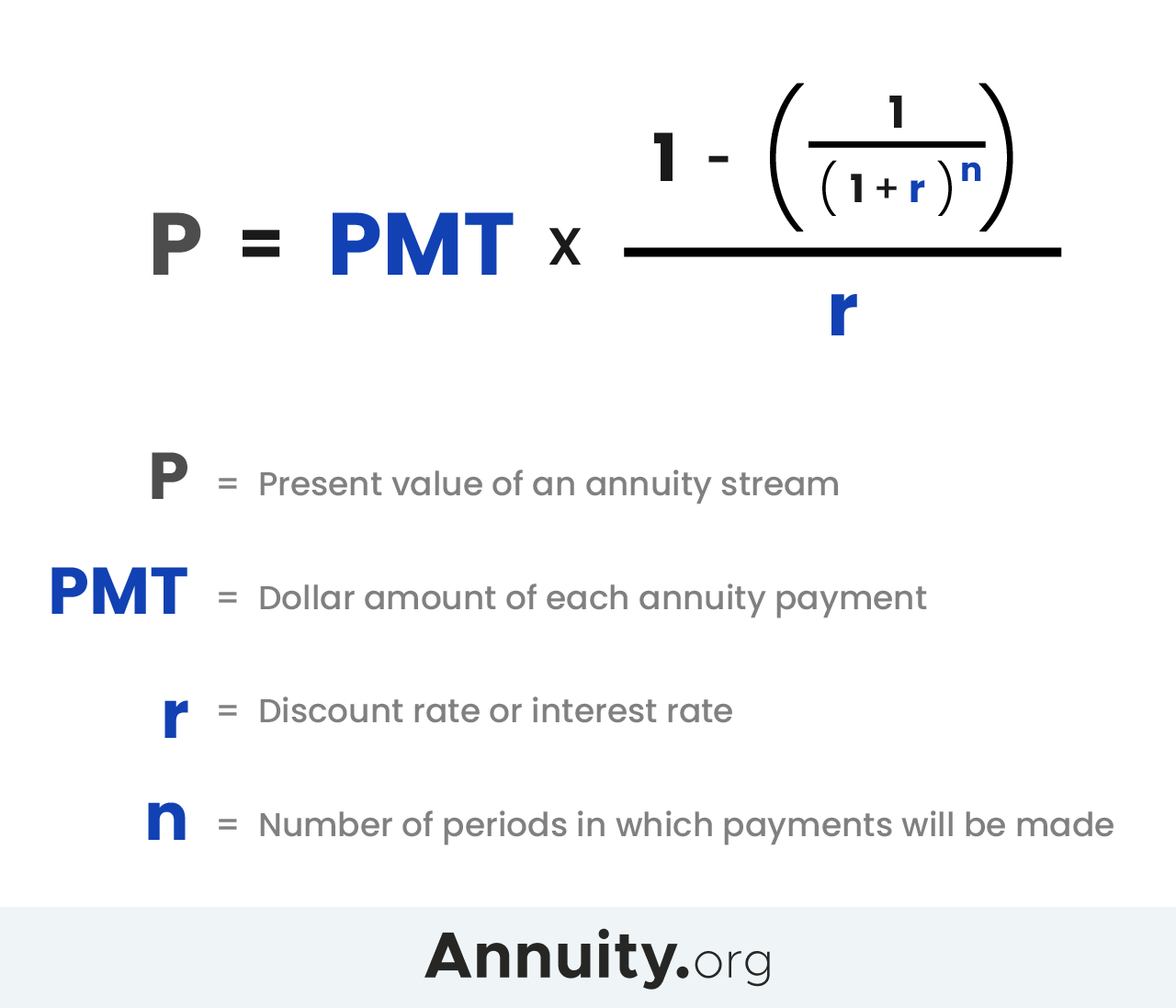

To find the present value, we use a formula that looks intimidating but is actually pretty logical. You’re essentially "discounting" each future payment back to the present day using a specific interest rate, often called the discount rate.

The standard formula is:

$$PV = P \times \frac{1 - (1 + r)^{-n}}{r}$$

In this setup, $PV$ is what we’re looking for. $P$ is the payment amount per period. The $r$ represents the interest rate per period, and $n$ is the total number of payments. If you’re doing this for a yearly payment, $r$ is the annual rate. If it's monthly, you have to divide that annual rate by 12.

Why the discount rate is everything

If you change the interest rate by even a fraction of a percent, the "present value" swings wildly. It’s the most sensitive part of the equation.

✨ Don't miss: Syrian Dinar to Dollar: Why Everyone Gets the Name (and the Rate) Wrong

Financial pros like those at Vanguard or BlackRock spend countless hours debating what discount rate to use. Why? Because it represents your "hurdle rate." If you use a 3% discount rate, you’re saying, "I could easily get 3% elsewhere with no risk." If you use 8%, you’re being more aggressive.

When interest rates in the real world go up, the present value of your annuity goes down. It’s an inverse relationship. If the bank is offering 5% on a CD, that future $1,000 payment from your annuity looks less attractive than it did when the bank was only offering 1%.

Ordinary Annuities vs. Annuities Due

Most people assume payments happen at the end of a period. That’s an "ordinary annuity." Most car loans or mortgages work this way. But if you’re dealing with rent or certain insurance products, payments happen at the beginning of the month. That’s an "annuity due."

Because you get the money sooner in an annuity due, it’s worth more. You have more time for that first payment to earn interest. To calculate this, you just take the ordinary annuity result and multiply it by $(1 + r)$. It’s a small tweak that makes a massive difference over twenty or thirty years.

Real-world example: The $50,000 windfall

Let's say you won a small local lottery. They offer you $5,000 a year for 10 years. That’s $50,000 total, right? Well, not in today’s value.

If we assume a modest 5% discount rate, we plug the numbers in.

🔗 Read more: New Zealand currency to AUD: Why the exchange rate is shifting in 2026

- $P = 5,000$

- $r = 0.05$

- $n = 10$

After running the math, the present value is actually roughly $38,608.

The "loss" of nearly $11,400 represents the interest you could have earned if you had all that money upfront on day one. If a company offers to buy your future payments for $30,000, you now know they are lowballing you. You have the mathematical high ground.

Misconceptions that cost people money

People often forget about inflation.

While calculating the present value of an annuity helps you understand the investment value, it doesn’t always account for the fact that $1,000 in the year 2045 might only buy a bag of groceries. To be truly safe, experts often use a "real" interest rate—the nominal rate minus the expected inflation rate.

Another mistake? Ignoring the tax implications. If your annuity is inside a 401(k) or a traditional IRA, that "present value" is actually smaller because Uncle Sam is going to take his cut when the money eventually hits your bank account. Always calculate your "after-tax" present value if you want a dose of reality.

The role of risk and creditworthiness

Not all annuities are created equal. A "guaranteed" payment from the U.S. Treasury is worth more than a "guaranteed" payment from a struggling startup.

💡 You might also like: How Much Do Chick fil A Operators Make: What Most People Get Wrong

When you choose a discount rate, you have to factor in "risk." If there’s a chance the entity paying you might go bust in five years, your discount rate should be much higher to compensate for that danger. This is why corporate bonds pay more than government bonds. You’re being paid to take on the anxiety of a potential default.

What about "Perpetuities"?

Some things, like certain UK government bonds (Consols) or preferred stocks, theoretically pay out forever. That’s a perpetuity.

Calculating the present value here is actually simpler. You just divide the payment by the interest rate ($PV = \frac{P}{r}$). If you get $100 a year forever and the rate is 5%, the value is $2,000. It’s a clean, elegant bit of math, though true "forever" payments are rare in the wild.

Steps to run your own numbers

Don't just trust a random online calculator without knowing what's happening under the hood.

- Identify your timing. Are payments monthly, quarterly, or annually?

- Determine your discount rate. Look at current 10-year Treasury yields for a "risk-free" baseline, then add a bit if the payer is a private company.

- Check the type. Is it an annuity due or an ordinary annuity?

- Run the calculation. Use the formula or a spreadsheet function like

=PV(rate, nper, pmt).

Practical Next Steps

Start by auditing any future income streams you're expecting. If you're looking at a pension plan or a structured settlement offer, get the exact terms—payment amount, frequency, and duration. Use a conservative discount rate (currently around 4-5% is a standard baseline for low-risk calculations) to find your "walk-away" price.

If you are offered a lump sum buy-out of an annuity, never accept an amount lower than your calculated present value unless you have an immediate, high-interest debt that needs to be nuked. For those managing their own retirement, compare the present value of your expected Social Security benefits against your total savings to see how much of your "wealth" is actually tied up in these time-delayed payments. This provides a much clearer picture of your actual net worth today.