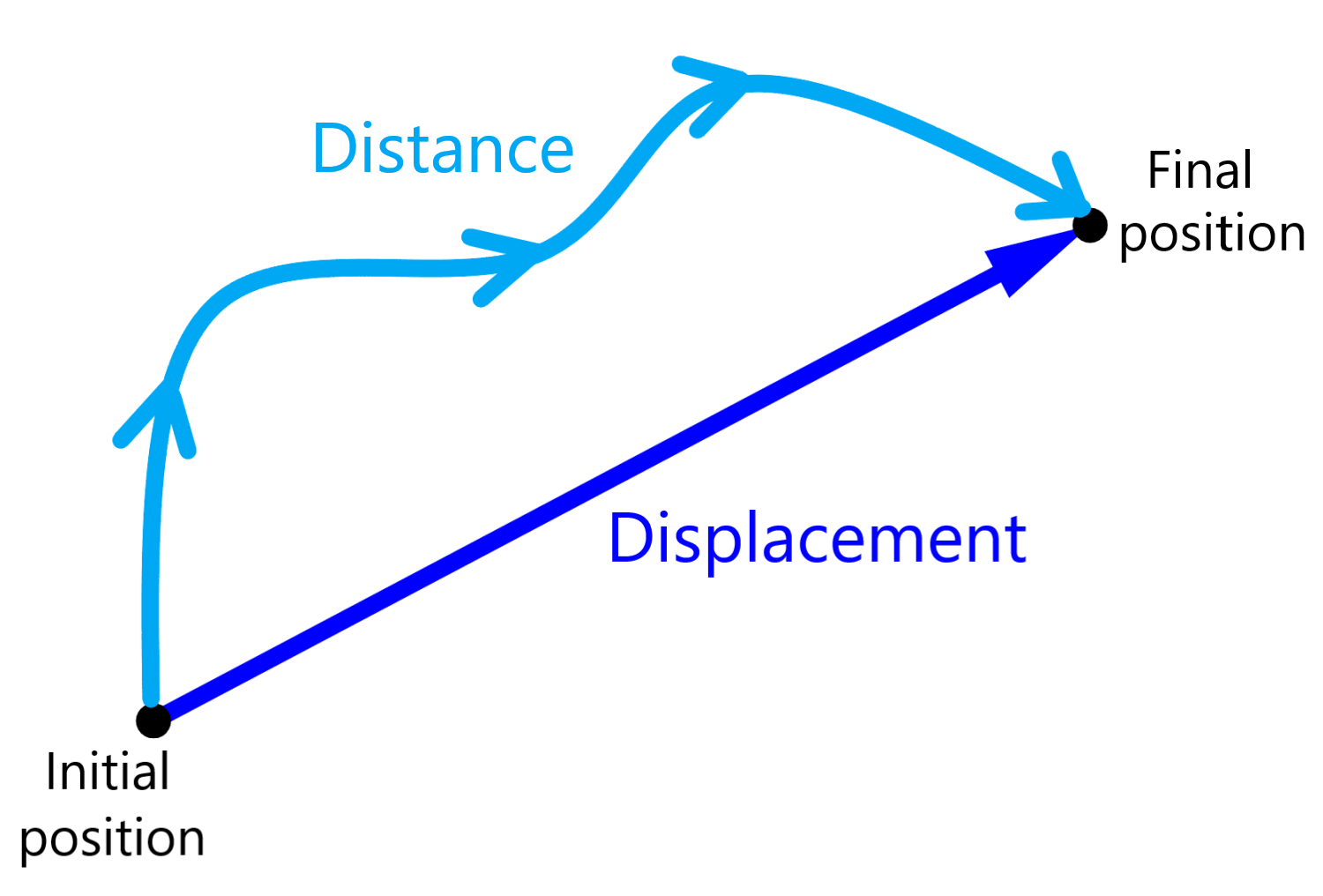

You're standing at a trailhead. You hike three miles up a winding path, realize you forgot your water bottle in the car, and hike three miles right back down. Your legs are burning. Your fitness tracker says you’ve crushed six miles. But if you ask a physicist about your displacement, they’ll look you dead in the eye and tell you that you’ve gone nowhere. Zero. Zilch.

That’s the first hurdle. To understand how do you calculate distance in physics, you have to stop thinking like a hiker and start thinking like a bookkeeper. Distance is the total ground covered. It doesn't care about direction. It's "scalar," which is just a fancy way of saying it’s a number without a compass attached to it. If you move, the odometer clicks up. It never goes backward.

The Basic Math Everyone Forgets

At its most stripped-down level, distance is just a product of how fast you were going and how long you were doing it. We’ve all used this intuitively. If you drive 60 miles per hour for two hours, you’ve gone 120 miles. Simple.

In a formal setting, we use the formula:

$$d = v \times t$$

But here is where things get messy in the real world. This formula only works if your speed is constant. If you’re stop-and-go in city traffic, $v$ isn't a single number anymore; it's an average. This is usually where students start to tune out because the variables look like alphabet soup. Honestly, it’s just bookkeeping. If you want the total distance, you calculate the distance for each little segment of the trip and add them all together.

When Gravity Gets Involved

Things get spicy when you aren't just moving at a steady cruise. Imagine you drop a rock off a bridge. It starts at zero miles per hour. A second later, it’s zipping along. A second after that, it's screaming. Because the velocity is changing—that's acceleration—the simple $d = vt$ formula breaks. It's useless here.

To figure out how far that rock fell, you need the kinematic equation for constant acceleration. It looks intimidating, but it's the backbone of classical mechanics:

$$d = v_{i}t + \frac{1}{2}at^{2}$$

👉 See also: Why 2 to the fifth power is the secret number behind your digital life

In this scenario, $v_{i}$ is your starting speed (zero if you just let go), $a$ is the acceleration (usually $9.81 m/s^{2}$ on Earth), and $t$ is the time it spent falling.

Why the squared term on the time? Because as time goes on, the object isn't just moving longer; it's moving faster every single millisecond. The distance grows exponentially. If you double the time a rock falls, it doesn't fall twice as far—it falls four times as far. Gravity is a beast like that.

The Coordinate Plane and the Ghost of Pythagoras

Sometimes you aren't moving in a straight line or falling down a hole. You're moving across a field. You walk 40 meters East and then 30 meters North.

How do you calculate distance in physics when you’re dealing with coordinates?

If we are talking about total distance, you just add 40 and 30 to get 70. Easy. But usually, physics problems are actually asking you for the shortest distance between two points, which is displacement. This is where you summon your middle-school geometry and use the Pythagorean theorem.

$$c = \sqrt{a^{2} + b^{2}}$$

📖 Related: How Do I Log Out of Google Account: The Simple Steps and One Big Catch

In our field example, the "straight-line" distance (displacement) would be the square root of $40^{2} + 30^{2}$, which equals 50 meters. It’s a classic 3-4-5 triangle. Most real-world navigation systems, like the GPS in your phone, are constantly toggling between these two definitions—tracking your actual path (distance) while calculating the "as the crow flies" vector to your destination.

The Calculus Secret

Wait. What happens if the acceleration isn't constant? What if you're in a rocket where the weight changes as fuel burns, or a car where the driver is pulsing the brakes?

This is where algebra fails and calculus takes over. If you have a graph of velocity over time, the distance is literally just the area under the curve. If the curve is a jagged, weird shape, you use an integral. You're basically slicing the trip into infinitely small slivers of time, calculating the tiny distance covered in each micro-second, and stacking them all up.

It sounds like overkill. But for NASA engineers landing a rover on Mars, those "micro-segments" are the difference between a soft landing and a multi-billion dollar crater.

Common Traps That Kill Your Grades

I've seen so many people trip up on units. It’s the silent killer. You cannot multiply miles per hour by minutes and expect a coherent answer. You'll get "mile-minutes per hour," which isn't a thing anyone wants.

- Always convert first. If your speed is in meters per second ($m/s$), your time must be in seconds.

- Watch the signs. In distance calculations, "negative" doesn't exist. If you run 5 miles backward, you still ran 5 miles.

- Average speed vs. Instantaneous speed. Your speedometer shows instantaneous speed. Your GPS "Time to Arrival" uses average speed. Don't mix them up in your equations.

Putting It Into Practice

If you're trying to solve a problem right now, stop staring at the numbers and follow this workflow. It works every time.

✨ Don't miss: Adblock Plus Chrome Addon: Why It Still Dominates (And Where It Struggles)

First, identify if the object is accelerating. If it's a car at a steady 60, use $d=vt$. If it’s something falling, rolling down a hill, or a car slamming on the brakes, you need the $\frac{1}{2}at^{2}$ version.

Second, draw it. Even a crappy stick-figure drawing helps. If the path turns, you're likely looking at a geometry problem involving the Pythagorean theorem.

Third, check your units. Seriously. Convert everything to SI units (meters, seconds, kilograms) before you touch a calculator. It saves so much heartache.

Actionable Next Steps

- Check your Odometer: Next time you're in a car, watch the odometer versus your GPS "distance to destination." The difference is the gap between path distance and displacement.

- Master the 1-D Kinematics: Practice the $d = v_{i}t + \frac{1}{2}at^{2}$ equation using a simple "drop test" (dropping an object from a known height) to see if you can predict the time it takes to hit the floor.

- Visualizing Areas: If you have a fitness app that shows velocity graphs, try to "eye-ball" the area under the peak. That area is the total distance you covered during that sprint.

Understanding these mechanics isn't just for passing a test. It’s how we map the stars, how your phone knows you’re walking instead of driving, and how we understand the very limits of how fast things can move in our universe.