Ever looked at your gross pay and then at your bank deposit and felt a physical pang of loss? It’s a universal experience. You see that big number at the top of the offer letter, but the reality that hits your checking account every two weeks feels… significantly lighter. Trying to calculate taxes to be taken out of paycheck is honestly a bit of a nightmare because the IRS doesn't just take one flat slice. It’s a layered cake of deductions, and some of those layers change depending on how you filled out a form you probably haven't looked at in three years.

Tax season shouldn't be the only time you think about this. If you’re over-withholding, you’re basically giving the government an interest-free loan while you struggle to pay for groceries. If you’re under-withholding, you’re going to get hit with a massive bill—and potentially penalties—come April. Most people treat their paystub like a mysterious receipt from a restaurant where they didn't see the prices. But you can actually predict this stuff with a fair amount of accuracy if you stop looking at the "bottom line" and start looking at the math behind the madness.

The W-4 is the actual boss of your paycheck

Everything starts with the Form W-4. You remember it. It’s that confusing document you filled out in a rush on your first day of work while HR was hovering over your shoulder. In 2020, the IRS completely redesigned this form. They got rid of "allowances," which used to be the way we all guesstimated our taxes. Now, it’s much more data-driven.

If you haven't updated your W-4 since the Trump-era tax changes or since you got married, had a kid, or started a side hustle, your calculations are already wrong. The current form asks for specific dollar amounts for dependents and other income. If you leave it blank, the payroll software assumes you’re taking the standard deduction and have no other income sources. For a single person with one job, that works fine. For anyone with a more complex life, it’s a recipe for a tax-time surprise.

FICA is the tax that never sleeps

Before the IRS even looks at your income tax, FICA takes its bite. This is the Federal Insurance Contributions Act. It covers Social Security and Medicare. Unlike federal income tax, which is progressive, FICA is mostly a flat rate. You pay 6.2% for Social Security and 1.45% for Medicare. Your employer matches those amounts.

Wait. There is a "cap" on the Social Security portion. In 2024, that cap was $168,600. For 2025, it’s $176,100. If you’re a high earner and you notice your paycheck suddenly gets bigger in November or December, it’s probably because you hit that ceiling and the Social Security tax stopped. It’s like a tiny holiday bonus from the government, though it resets every January 1st. Medicare, however, has no cap. In fact, if you earn over $200,000 (single filer), you actually pay an extra 0.9% in Additional Medicare Tax. Success has a price.

Understanding the "Tax Bracket" trap

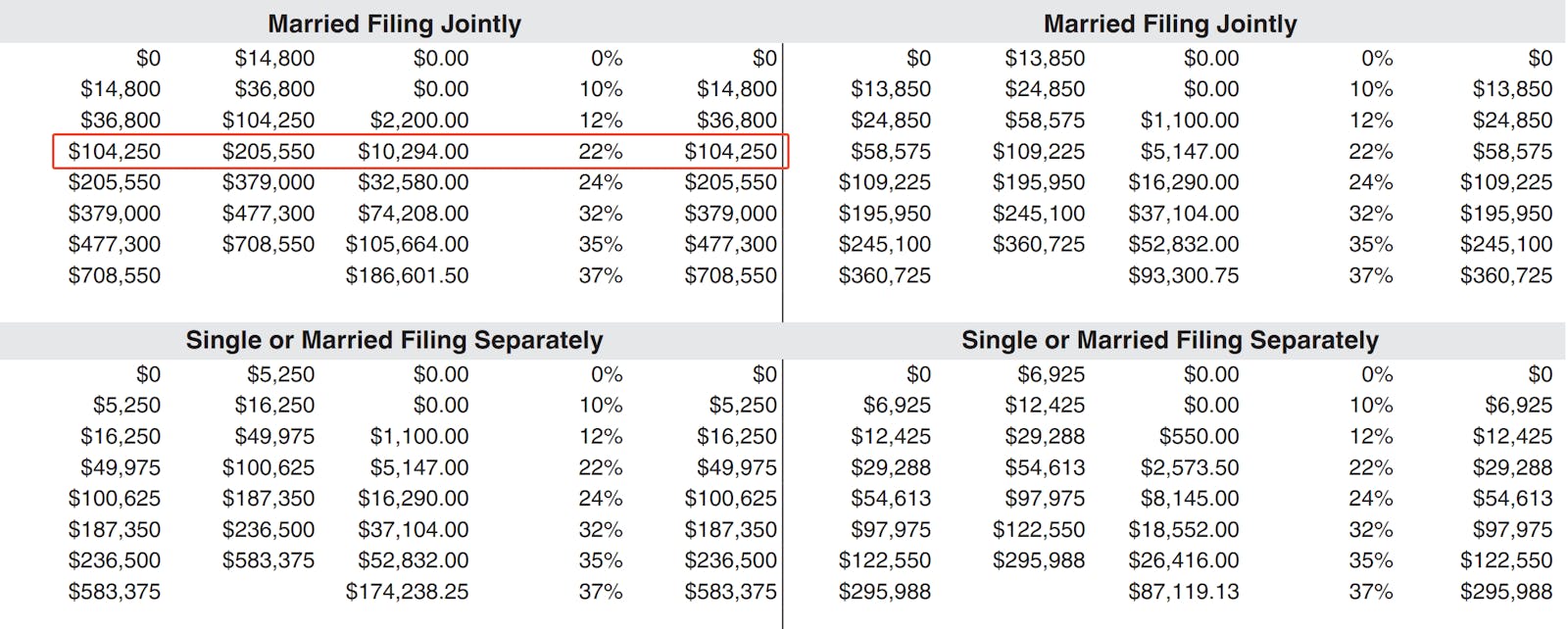

People talk about being in a "24% tax bracket" like the government takes 24 cents of every single dollar they earn. That is not how it works. We have a progressive tax system. Think of it like a series of buckets.

🔗 Read more: USD to UZS Rate Today: What Most People Get Wrong

The first chunk of your money goes into the 10% bucket. Once that bucket is full, the next chunk goes into the 12% bucket. Only the money that spills over into the highest bucket gets taxed at that top rate. This is why when you try to calculate taxes to be taken out of paycheck, you can't just multiply your gross pay by 20% and call it a day.

You also have to account for the Standard Deduction. For the 2025 tax year, the standard deduction is $15,000 for single filers and $30,000 for married couples filing jointly. This is "invisible" money. The IRS pretends you didn't even earn it. So, if you make $60,000 a year as a single person, you’re really only being taxed on $45,000. That’s a huge distinction that most "back of the napkin" calculations miss.

State and Local: The "Where You Live" Penalty

If you live in Florida, Texas, or Washington, congrats—you can skip this part. You have no state income tax. But if you’re in California, New York, or Oregon, you’re looking at another 5% to 13% disappearing from your check.

Some places, like Philadelphia or New York City, even have local or city taxes. These are often flat rates, but they add up. When you’re trying to manually calculate your take-home pay, you have to find your state’s specific withholding tables. Most states follow the federal lead, but some have their own quirky "allowance" systems that didn't change when the federal government updated the W-4. It’s a mess. Honestly, it's the biggest reason people's DIY spreadsheets fail.

Pre-tax vs. Post-tax: The math of benefits

Your 401(k) contribution is your best friend. Why? Because it’s "pre-tax." If you earn $2,000 in a pay period and put $200 into your 401(k), the IRS acts like you only earned $1,800. You are effectively lowering your taxable income before the tax man even gets a chance to look at it.

Health insurance premiums are usually the same way. Most employer-sponsored plans are "Section 125" plans, meaning the premiums come out before taxes.

💡 You might also like: PDI Stock Price Today: What Most People Get Wrong About This 14% Yield

- Pre-tax deductions: 401(k), 403(b), Health Insurance, HSA, FSA.

- Post-tax deductions: Roth 401(k), Life Insurance (usually), Disability Insurance (sometimes), Union dues.

If you’re contributing to a Roth 401(k), you’re paying taxes on that money now so you don’t have to later. It’s great for your 65-year-old self, but it makes your current paycheck look smaller.

The "Checkup" you actually need to do

The IRS has a tool called the Tax Withholding Estimator. Use it. Seriously. It’s not a fancy "clickbait" calculator; it’s the actual logic the government uses. To use it right, you need your most recent paystub and your last tax return.

If you realize you’re on track to owe $3,000 at the end of the year, you can fix it right now. On the W-4, there’s a line (Step 4c) for "Extra Withholding." You can literally tell your boss to take out an extra $100 per check. It sounds painful, but it’s way better than a $3,000 surprise in April when you’ve already spent your "extra" money on a summer vacation.

Why your "Refund" is actually a failure

We've been conditioned to love tax refunds. We treat them like a lottery win. But a $5,000 refund just means you overpaid the government by $416 every single month. That’s money that could have been in a high-yield savings account or used to pay down high-interest credit card debt.

The goal of learning to calculate taxes to be taken out of paycheck isn't to get a huge refund. The goal is to "break even." You want to owe $0 and get $0. That means you managed your cash flow perfectly throughout the year.

Real-world example: The $75,000 Salary

Let’s look at a single person in a state with no income tax (like Tennessee) making $75,000 a year, paid bi-weekly (26 pay periods).

📖 Related: Getting a Mortgage on a 300k Home Without Overpaying

- Gross Pay: $2,884.62 per check.

- FICA (7.65%): -$220.67.

- Federal Income Tax (Estimated): This is where it gets tricky. After the standard deduction, their effective tax rate is likely around 12-14%. Let’s say -$350.

- 401(k) Contribution (5%): -$144.23.

- Health Insurance: -$100.00.

Estimated Take-Home: ~$2,069.72.

In this scenario, nearly $800 vanished. If this person lived in California, they’d lose another $150+ to the state. It's a sobering reality check, but knowing these numbers prevents you from overspending based on your gross salary.

Common mistakes to avoid

One big pitfall is forgetting about bonuses. Bonuses are often "supplemental wages." Employers frequently withhold a flat 22% for federal taxes on bonuses. This often leads to over-withholding, which is why your bonus checks look so much smaller than you expect. You'll get that money back at tax time, but you won't see it on the Friday the bonus hits.

Another mistake? Not adjusting for life changes. If you got married, your tax bracket changed. If you bought a house and are itemizing (though fewer people do this now with the higher standard deduction), your withholding should change. If you have a side gig where you're an independent contractor (1099), you should actually be increasing your W-2 withholding to cover the taxes on your side income. This saves you from having to pay quarterly estimated taxes.

How to take control of your check

Stop guessing. Grab your last three paystubs and look for the "Year to Date" (YTD) column. Compare the total federal tax withheld to what you expect to owe based on the current tax brackets. If the math doesn't align, head to the HR portal and submit a new W-4. It takes five minutes and can save you months of financial stress.

Your Action Plan:

- Download your last two paystubs. Check if your withholding has been consistent.

- Run the IRS Tax Withholding Estimator. Do this specifically after any salary change or life event.

- Check your state's Department of Revenue site. See if they have a specific calculator for state-level withholding, especially if you live in a high-tax state.

- Adjust your 401(k). If you find you have more take-home pay than you thought, bump that contribution up by 1%. You won't even feel it, but your future self will thank you.

- Audit your "other" deductions. Sometimes we pay for life insurance or legal plans through work that we totally forgot we signed up for during open enrollment. Cancel what you don't need to boost that net pay.