Living on the water sounds like a fever dream. You wake up, the floor is gently swaying, and you’re literally inches away from a morning swim. It’s the ultimate "main character" lifestyle move. But honestly, a tiny house on water is a whole different beast compared to those cute cabins on wheels you see on Instagram. It’s not just a smaller house. It’s a vessel. It’s a permit nightmare. It’s a specialized piece of engineering that most people underestimate until they’re knee-deep in maritime law.

The difference between a houseboat and a floating home

First, let’s clear up the confusion because people use these terms interchangeably, and they shouldn't. A tiny house on water usually falls into one of two categories: a houseboat or a floating home.

Houseboats have engines. They’re meant to move. You can untie the lines and cruise down the river if you get bored of the view. A floating home? That’s basically a house built on a concrete or steel stringer float. It doesn't have a motor. It’s permanently (or semi-permanently) moored to a dock with utility hookups. If you try to "drive" a floating home, you’re just going to have a very expensive accident.

Understanding this distinction is the first step toward not losing your shirt. Floating homes are often treated as real estate, while houseboats are titled like boats. This changes everything from your taxes to your financing. Most banks will laugh you out of the room if you ask for a standard 30-year mortgage on a tiny house on water that has an outboard motor. You’re looking at marine loans, which usually have higher interest rates and shorter terms—think 10 to 15 years.

Why the "tiny" movement hit the waves

The math is simple. Land is expensive. In cities like Seattle, Sausalito, or Victoria, B.C., the cost of a dirt-lot is astronomical. People started looking at the marinas and realized that while slip fees aren't exactly "cheap," they’re often a fraction of a monthly mortgage in a high-density zip code.

📖 Related: Coach Bag Animal Print: Why These Wild Patterns Actually Work as Neutrals

Take the iconic Lake Union in Seattle. It’s the poster child for this movement. You have these incredible, high-tech tiny structures designed by firms like Dan Nelson of Designs Northwest Architects. They aren't just shacks. They use rain-screen cladding and glass walls to maximize the light reflecting off the water. It’s smart. It’s efficient. It’s also incredibly cramped if you don’t know how to purge your belongings.

The brutal reality of maintenance

Water is a destroyer. It eats everything. If you own a tiny house on water, you are in a constant state of war against salt, rust, and rot.

Steel hulls need to be pulled out of the water every few years to be scraped and painted. This is called "dry docking," and it is expensive. We’re talking thousands of dollars just to get the house out of the water before you even pay for the actual repairs. If you have a concrete float, you’re in better luck regarding longevity, but you still have to worry about electrolysis and marine growth.

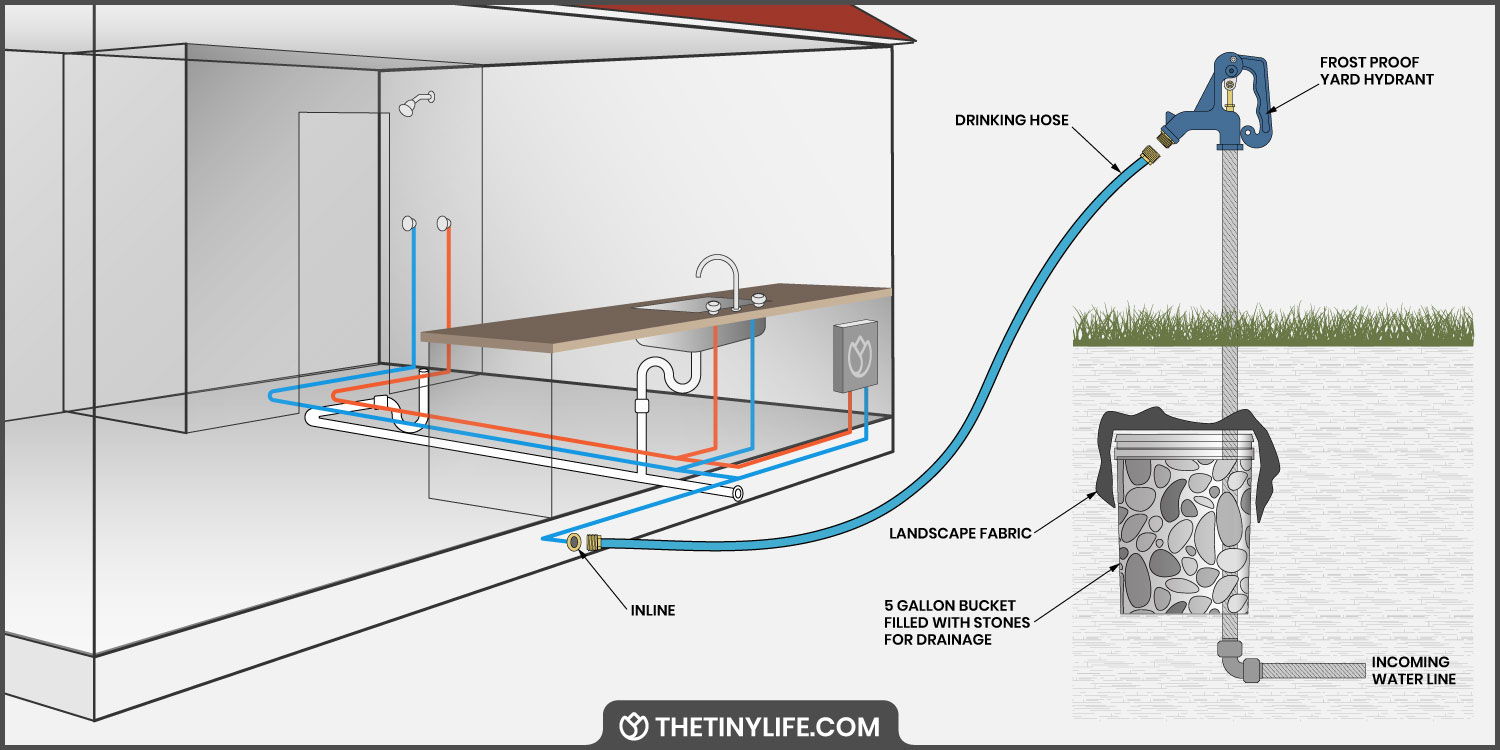

Then there’s the plumbing. Let’s talk about black water. In a normal house, you flush and forget. On a tiny house on water, that waste has to go somewhere. Some high-end floating homes are hooked directly into the city sewer lines via flexible hoses. Most houseboats, however, use holding tanks. You have to monitor your levels. You have to pay for a "pump-out" boat to come by once a week, or you have to unhook and drive to a station. It’s not glamorous. It’s a chore.

👉 See also: Bed and Breakfast Wedding Venues: Why Smaller Might Actually Be Better

Zoning, slip rights, and the "gray" area

Where do you put it? That’s the million-dollar question.

You can’t just drop an anchor anywhere and call it home. Most cities have strict "live-aboard" percentages for marinas. A marina might have 200 slips but only 10 "live-aboard" permits. These permits are like gold. Sometimes they stay with the boat; sometimes they stay with the person. If you buy a tiny house on water without a guaranteed slip, you basically bought a very expensive floating ornament with nowhere to go.

There's also the "Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)" and various state-level departments of ecology to contend with. In many jurisdictions, new floating homes are actually banned because of their impact on the underwater ecosystem. They block sunlight, which kills eelgrass and disrupts salmon migrations. If you want to live this life, you’re often buying an existing, older "grandfathered" structure and renovating it rather than building new.

Living small on a liquid foundation

Space management becomes a religion. In a 300-square-foot floating cottage, every inch has to work.

✨ Don't miss: Virgo Love Horoscope for Today and Tomorrow: Why You Need to Stop Fixing People

- Multi-purpose furniture: Your bed is probably also your dresser. Your stairs are probably also your pantry.

- Weight distribution: This is something land-dwellers never think about. If you put all your heavy books or a cast-iron stove on the left side of a tiny house on water, the whole house will tilt. You’ll be living at a 5-degree angle. You have to balance your load.

- Moisture control: Dehumidifiers are non-negotiable. Living on water means high humidity 24/7. Without proper ventilation, your walls will grow a fuzzy coat of mold within a single season.

The community vibe is different

There is a trade-off for all this hassle. The community.

Marina life is tight-knit. You’re living in close quarters with people who understand the struggle of a frozen dock pipe or a rogue storm surge. There’s a level of "we’re all in this together" that you just don't get in a suburban cul-de-sac. You’ll know your neighbors' business, and they’ll know yours. If your bilge pump starts screaming at 3:00 AM, three people will be on your dock with flashlights before you even wake up.

Is it actually sustainable?

A lot of people pivot to a tiny house on water because they want to go green. It's a mixed bag.

Solar panels work great because you usually have unobstructed sun on the water. Rainwater collection is a possibility, though filtering it for drinking takes a serious system. However, the materials used to build these houses—especially the flotation devices and the specialized marine paints—aren't always eco-friendly. You have to be intentional. Using a composting toilet can drastically reduce your environmental footprint and save you the headache of pump-outs, but you have to be okay with the "hands-on" nature of that system.

Actionable steps for the aspiring water-dweller

If you're serious about this, don't just go out and buy a boat. You'll regret it.

- Rent first. Go to a place like Sausalito or the Florida Keys and find an Airbnb that is an actual tiny house on water. Stay for at least a week during bad weather. It’s easy to love the life when it’s 75 degrees and sunny. It’s a different story when it’s raining sideways and the docks are icy.

- Inspect the hull. Never, ever buy a floating structure without a marine survey. Hire a professional to go under the water or put the boat in dry dock. If the hull is compromised, the house is worthless.

- Check the slip lease. Read the fine print of the marina agreement. Does the rent increase 10% every year? Can they kick you out if they decide to renovate the docks? Is the live-aboard permit transferable?

- Insurance is tricky. Many standard companies won't touch floating homes. You’ll need a specialized broker like Geico Marine or Jack Martin & Associates. Expect to pay a premium.

- Measure your tolerance for "quirks." Doors might stick depending on the tide. Spiders love docks. You will hear the water lapping against the hull at night—which is either soothing or maddening depending on who you are.

Living small on the water isn't about saving money, though it can happen. It’s about a different relationship with the world. You’re more tuned into the weather, the tides, and the seasons. It’s a high-maintenance love affair. If you’re okay with the "work" of it, there’s nothing else like it. Just make sure you know how to tie a proper cleat hitch before you move in.