You could literally buy a house from a catalog. Imagine flipping through a magazine, seeing a porch you like, and clicking "add to cart." Except, in 1930, you weren't clicking; you were filling out a form and mailing a check to Chicago. A few weeks later, a train would pull up to your local station with two boxcars full of 30,000 individual pieces of lumber, plumbing, and paint. Bungalow Sears kit homes 1930 were the original "some assembly required" project, and honestly, they put modern flat-pack furniture to shame.

The year 1930 was a weird time for Sears, Roebuck and Co. The Great Depression was starting to bite hard, but the "Modern Homes" catalog was still humming along. These weren't just cheap shacks for the desperate. They were high-quality, architecturally sound bungalows that used better wood than you’ll find in most new builds today. Old-growth yellow pine and cypress. No knots. Real plaster. It’s why so many of them are still there, looking better at nearly a century old than the stucco boxes built in the 90s.

The 1930 Catalog: A Last Hurrah for the Classic Bungalow

By 1930, the American obsession with the Craftsman style was starting to pivot toward "Period Revival" looks—think English Cottages or Spanish Colonials. But the bungalow remained the bread and butter. Why? Because they were efficient.

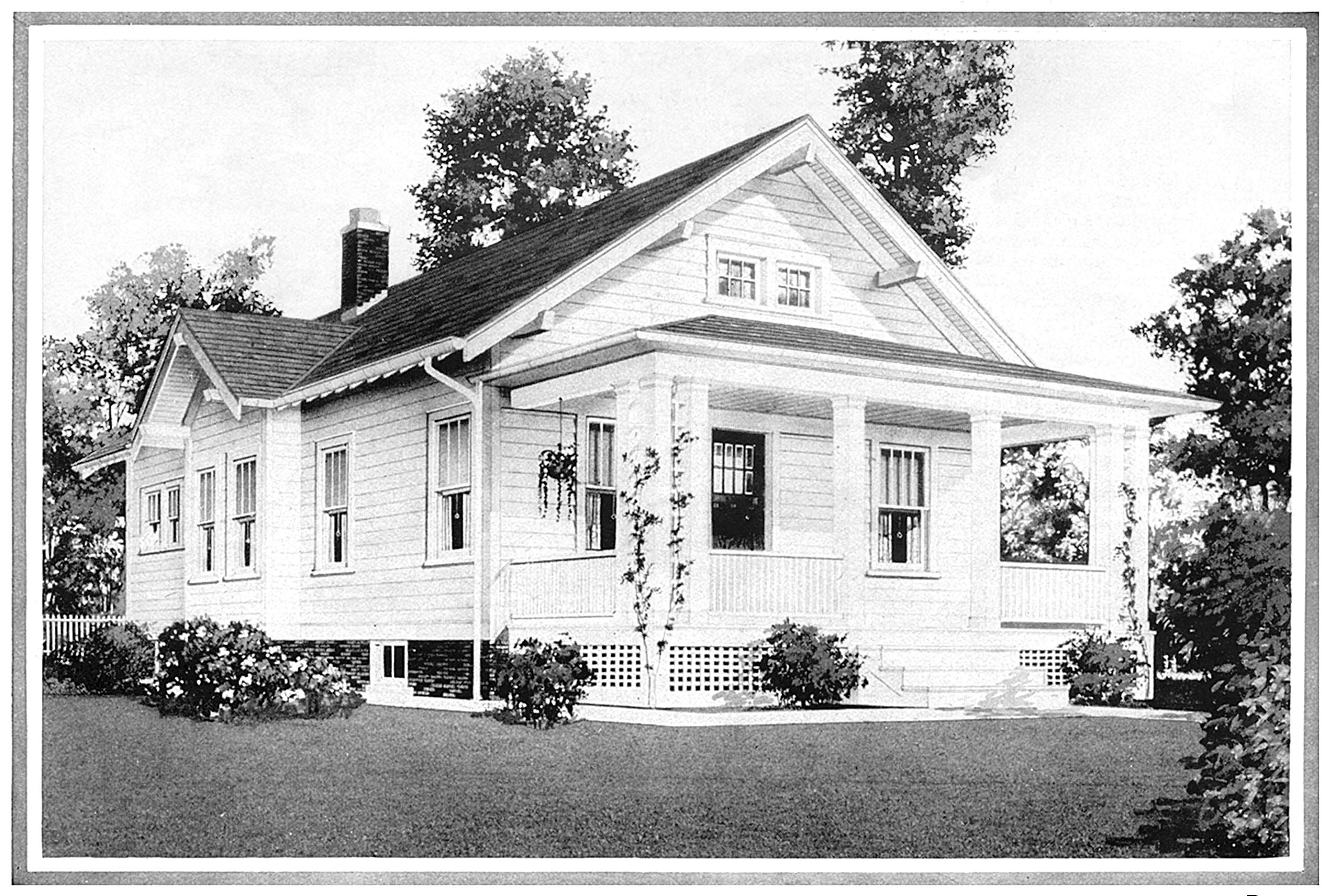

The "Argyle" or the "Winona" models were staples. Sears advertised them as "Honest-to-Goodness" homes. They were designed for the Everyman. If you look at the 1930 catalog specifically, you see a shift in the marketing. Sears started leaning heavily into the "Honor Bilt" brand. This was their top-tier line. It meant the framing members were pre-cut and fitted, much like a giant Lego set. The 1930 edition of the catalog was thick, hopeful, and surprisingly modern in its layouts.

People often think these kits were just for rural farmers. Not true. You’ll find clusters of bungalow Sears kit homes 1930 in suburban pockets of Ohio, Illinois, and Washington D.C. They were popular in "streetcar suburbs." A family would buy a narrow lot, order the kit, and spend their weekends hammering away with the help of neighbors. Or, if they were fancy, they'd hire a local contractor to assemble the Sears pieces.

Identifying a Real 1930 Sears Bungalow

Identifying these things is a bit of a sport for architectural historians like Rosemary Thornton. You can’t just look at the porch and know. You have to get dirty.

First, check the basement or the attic. Look at the exposed rafters. If it’s a genuine Sears home from around 1930, you’ll often find a letter and a three-digit number stamped into the wood. "A124" or "C452." This was the "map" for the homeowner to know which piece went where.

💡 You might also like: Hair Colors and Names: What Your Stylist Isn't Telling You About Those Salon Swatches

Another dead giveaway? The hardware. Sears used specific patterns for their doorknobs and backplates. The "Stratford" design or the "La Tosca" pattern are classic hallmarks. If you see a specific stylized "SR" on the back of a bathtub or a sink, you’ve hit the jackpot. However, keep in mind that by 1930, many people were also buying kits from competitors like Aladdin, Wardway (Montgomery Ward), or Gordon-Van Tine. A lot of those houses look strikingly similar to the Sears designs because, well, everyone was copying the same bungalow trends.

Why 1930 Was a Turning Point

It wasn't all sunshine and blueprints. The 1930s were brutal. Sears acted as the bank for many of these homes, offering mortgages to people who couldn't get them elsewhere. When the Depression hit full force, the company ended up having to foreclose on thousands of their own customers. It was a PR nightmare.

By the mid-30s, the kit home business was bleeding money. But the houses built in that 1929-1930 window represent the peak of the "Kit" era's engineering. They had mastered the logistics. The wood was kiln-dried and pre-fitted with a precision that was unheard of for mass-market housing.

The Survival of the "Honor Bilt" Standard

Sears used a "balloon framing" technique for years but transitioned more toward "platform framing" as codes evolved. The 1930 bungalows usually feature:

🔗 Read more: Target Gift Card Balance: Why It’s Not Always Where You Think It Is

- Double-strength glass in all windows.

- Clear-grade flooring (no knots in the wood).

- Goodyear rubber tiling in the kitchens (a high-tech luxury back then!).

- Pre-fitted joints that meant a novice could actually build a house that was square and level.

The "Argyle" and the "Maywood"

Let's talk about the specific models that dominated the 1930 landscape. The Argyle was a classic. It was a five-room bungalow with a massive front porch. It cost roughly $1,500 for the kit. Think about that. Even adjusted for inflation, that’s a steal for a house that will last 100 years.

Then there was the Maywood. It was a bit more "Cottage-esque." It had that clipped gable roof (sometimes called a jerkinhead roof) that gave it a storybook feel. These were the houses that defined the American dream before the "McMansion" ruined everything. They were small—usually under 1,000 square feet—but they used every inch. Built-in breakfast nooks. Ironing boards that folded out of the wall. Telephone niches. They were "tiny houses" before it was a hipster trend.

Misconceptions About Kit Homes

People think they were flimsy. They weren't. Honestly, they were often stronger than site-built homes of the same era. Because the lumber was cut in a centralized factory in Cairo, Illinois, the quality control was insane. If a piece of wood was warped, it didn't make it into the boxcar.

Another myth? That they all look the same. Sears offered dozens of customizations. You could flip the floor plan. You could add a sunroom. You could upgrade the shingles to slate. This is why two bungalow Sears kit homes 1930 on the same street might look totally different to the untrained eye.

How to Verify Your Home's Heritage

If you think you're living in one of these historical gems, don't just take the real estate agent's word for it. They love to claim a house is a "Sears Home" because it adds $20,000 to the price tag.

- Check the County Records: Look for a "Mechanic’s Lien." Sears often filed these when they provided the mortgage.

- Inspect the Lumber: Look for those stamped numbers on the joists in the basement.

- Look for Shipping Labels: Sometimes, if you're lucky, you'll find a scrap of paper or a stencil on the back of a piece of trim that says "Sears, Roebuck and Co."

- Compare Floor Plans: Use resources like the Sears Homes Archives. They have scanned catalogs where you can overlay your home's footprint onto the original 1930 designs.

The Legacy of the 1930 Mail-Order House

These houses represent a moment in time when high-quality architecture was accessible to the middle class. They weren't just buildings; they were kits of hope. Even though Sears stopped selling houses in 1940, the 1930 models remain some of the most sought-after real estate in older neighborhoods. They have "soul."

They remind us that "mass-produced" doesn't have to mean "disposable." In an age of 3D-printed houses and prefab modular pods, we’re essentially trying to rediscover what Sears perfected nearly a century ago.

📖 Related: How to Actually Score Black Friday Deals Futons Without Getting Scammed by Fake Markdowns

Next Steps for Homeowners and Enthusiasts

If you’re lucky enough to own or be looking at one of these homes, your first move should be preservation over renovation. Don't rip out those original windows if you can help it. Modern vinyl windows look like garbage in a 1930s frame. Instead, look into storm window inserts.

If you are trying to verify a property, start by checking the plumbing fixtures for any embossed "SR" marks. If the house has been updated, head to the attic and look at the rafters for those tell-tale ink stamps. Finally, join a community of "kit hunters." There are massive groups of enthusiasts on social media who can identify a model from a single photo of the roofline. Knowing exactly what you have isn't just cool—it's a way to protect a piece of American architectural history that literally came in a box.