Honestly, if you close your eyes and think of Buck Owens, what do you see? For a lot of people, it’s not the hard-driving honky-tonk pioneer who gave the Beatles a hit. It’s a guy in an overalls-wearing fever dream, standing in a literal cornfield, shouting "Hee Haw!" into a camera.

It’s a bit of a tragedy.

Buck Owens was a titan. He was the architect of the Bakersfield Sound, a raw, electric, and unapologetically loud alternative to the polished "Nashville Sound" that was dominating the 60s. He had 21 number-one hits. He played a red, white, and blue guitar like it was a weapon of mass percussion. Then, in 1969, he signed a contract to host a variety show.

That show was Hee Haw.

Most folks don't realize that while Hee Haw made Buck a household name and a very wealthy man, he actually grew to resent it. He felt it turned him into a caricature. A "cartoon donkey," as he famously put it in his autobiography, Buck 'Em!.

The $400,000 Cornfield: Why Buck Signed On

The origins of the show were weird. You’d think a show about rural humor would come from the South, right? Nope. Two Canadians, Frank Peppiatt and John Aylesworth, pitched the idea after seeing ratings spike whenever country stars appeared on variety hours.

They needed a face. They needed credibility. Buck Owens had both.

✨ Don't miss: Priyanka Chopra Latest Movies: Why Her 2026 Slate Is Riskier Than You Think

At the time, Buck was the king. He was selling out shows worldwide and running a business empire in Bakersfield, California. He wasn’t looking for a TV gig, but the money was—to put it lightly—insane.

The filming schedule was the real clincher. They’d tape an entire season’s worth of episodes in just a few weeks. Imagine that. You show up, put on some overalls, tell some "Knock, Knock" jokes, and pick your guitar for 14 days. Then, you spend the rest of the year counting the checks.

For a man who grew up picking cotton in the Texas heat during the Dust Bowl, that kind of "easy" money was impossible to turn down.

The Picking and the Grinning (and the Regret)

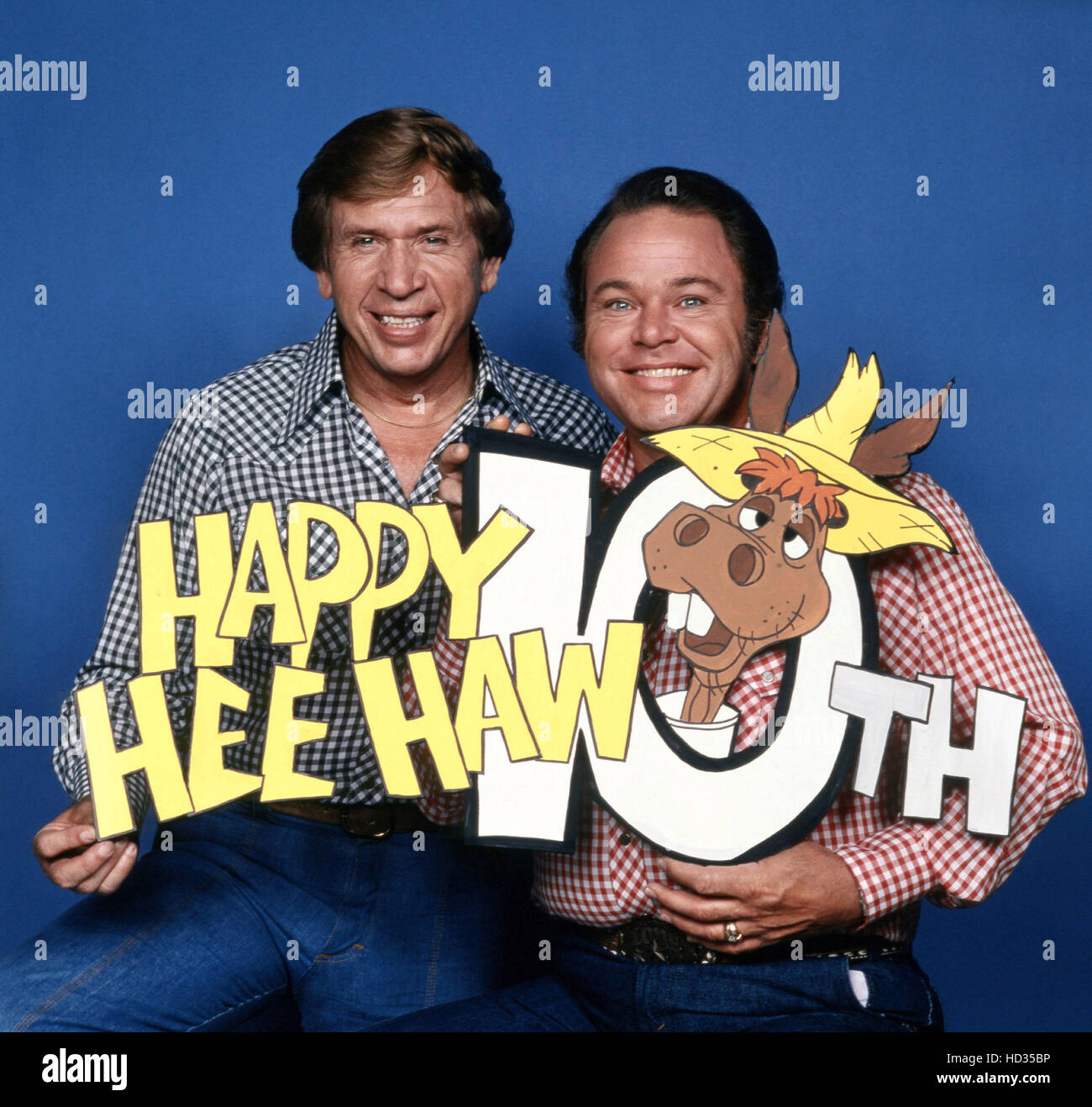

On screen, the chemistry between Buck and his co-host Roy Clark was legendary. Roy was the virtuosic, jolly foil to Buck’s cooler, more structured presence. Together, they birthed the phrase "Pickin' and Grinnin'."

But as the 1970s rolled on, the musical landscape started changing.

The very thing that made Hee Haw a hit—its relentless, cornball consistency—started to suffocate Buck’s recording career. Radio programmers began to see him as a "TV personality" rather than a serious artist. When his longtime musical partner and best friend Don Rich died in a tragic motorcycle accident in 1974, the heart went out of Buck's music.

🔗 Read more: Why This Is How We Roll FGL Is Still The Song That Defines Modern Country

Without Don, the Bakersfield Sound lost its edge. Buck went through the motions on TV, but he was hurting. He felt trapped in the cornfield.

He stayed until 1986. Seventeen years.

The Dwight Yoakam Salvation

By the mid-80s, Buck had basically retired. He was living in Bakersfield, running his radio stations, and staying away from the studio. He thought his time was over.

Then came a kid with a cowboy hat pulled low and a voice that sounded like 1962. Dwight Yoakam didn't care about the cornfield. He cared about the Telecaster twang.

Dwight famously tracked Buck down and practically begged him to come back. The result was "Streets of Bakersfield," which hit number one in 1988. It was the ultimate "I told you so." It proved that Buck wasn't just a guy on a variety show; he was a living legend who could still school the young guns.

The Legacy Beyond the Overalls

If you visit Bakersfield today—or at least, if you had visited before the recent headlines—you'd see the Crystal Palace. It’s the temple Buck built to the music he loved.

💡 You might also like: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

Sadly, in late 2025, the Owens family announced the venue would be closing its doors after nearly 30 years. It’s a gut-punch for fans of real country music. The Palace wasn’t just a restaurant; it was a museum of the Bakersfield Sound, housing that iconic red, white, and blue guitar and the memories of a man who fought to be more than a punchline.

What We Can Learn From the Buck Owens Story

Buck’s journey with Hee Haw is a massive lesson in brand identity. You can be the best in the world at what you do, but if you let the world define you by your easiest work, the "real" you can get lost in the shuffle.

But here’s the thing: Buck eventually reclaimed his name. He showed that you can survive the "cornfield" if your foundation is built on genuine talent.

How to Explore the Real Buck Owens:

- Listen to the "Live at Carnegie Hall" (1966) album. This is Buck and the Buckaroos at their absolute peak. It’s loud, it’s tight, and it has zero jokes about watermelons.

- Watch the "Streets of Bakersfield" music video. It captures the passing of the torch from the old guard to the new, and you can see the genuine joy in Buck's eyes as he realizes people still care about his music.

- Read Buck 'Em! The Autobiography of Buck Owens. It’s blunt. It’s honest. He doesn't hold back on how much he hated some of those TV sketches.

Buck Owens died in 2006, just hours after performing at the Crystal Palace. He died doing what he loved, not what paid the most. That’s the real story. The overalls were just a costume; the music was the man.

To truly understand the impact of the Bakersfield Sound, start by listening to the 1960s Capitol Records recordings. Pay attention to the "click" of the drums and the "twang" of the Telecaster—that is the DNA of modern country, and it has nothing to do with a laugh track.