He was a big, clumsy guy with a limp. Before he was "Brother Lawrence," he was Nicolas Herman, a soldier who survived the brutal Thirty Years' War only to end up working as a footman where he basically broke everything he touched. He called himself a "great awkward fellow." If you saw him in the 1600s, you probably wouldn't think, Hey, there goes a spiritual giant. You’d probably just move your glass away from the edge of the table.

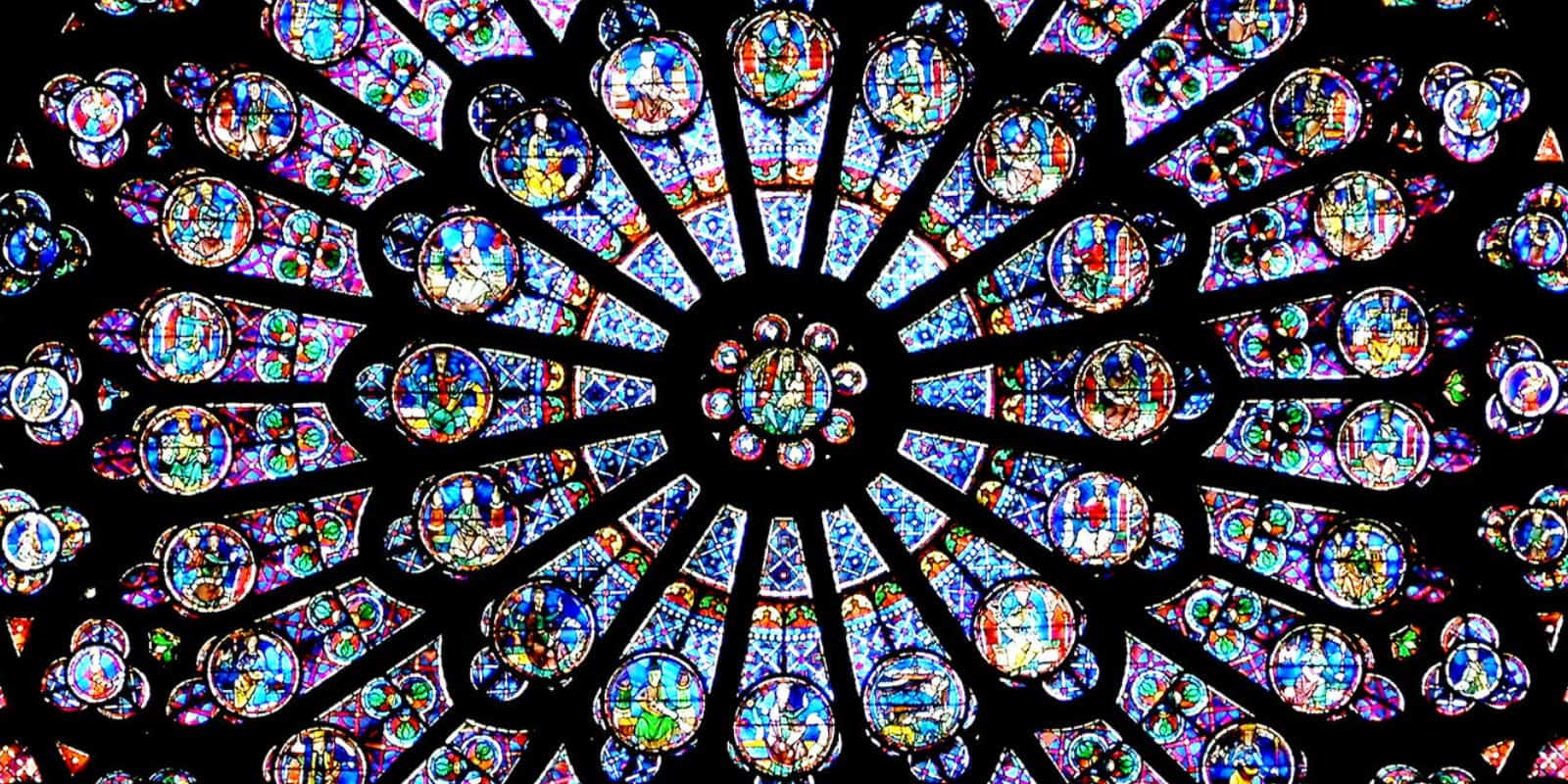

But this clumsy lay brother at a Carmelite monastery in Paris ended up figuring out something that modern mindfulness apps are still trying to sell us for $14.99 a month. The Brother Lawrence practice of the presence of God isn't some complicated theological framework. It's actually the opposite. It is the radical idea that washing a greasy pot in a loud kitchen is just as holy as praying in a cathedral.

Honestly, we’ve made spirituality way too hard. We think we need retreats, silent hours, or perfect lighting. Lawrence basically told everyone they were overthinking it. He spent most of his life in a kitchen he hated, surrounded by people who annoyed him, and somehow stayed happier than most of us on vacation.

The Kitchen Monk’s Weird Secret

Most of what we know about this guy comes from The Practice of the Presence of God, a tiny book compiled after he died in 1691. It wasn't even a book he wrote; it was just his letters and notes from conversations people had with him. One of those people was Joseph de Beaufort, the Grand Vicar to the Archbishop of Paris. Beaufort was shocked that this uneducated kitchen worker seemed more connected to the divine than the scholars.

The core of the Brother Lawrence practice of the presence of God is the "habitual, silent, and secret conversation of the soul with God." That sounds fancy, but in practice, it just means he didn't stop talking to God when he finished his prayers. He just kept the conversation going while he was peeling onions or fixing sandals.

He didn't see a "sacred-secular" divide. To him, there was no difference between the time of business and the time of prayer. He famously said that he possessed God as quietly in the heat of his kitchen business as if he were upon his knees before the Blessed Sacrament.

That's a massive claim.

Think about the last time you were stuck in traffic or dealing with a broken printer. Your first instinct probably wasn't "This is a holy moment." Lawrence’s "secret" was that he refused to let his mind wander into the past or the future. He stayed right there, in the mess, doing the work for the "love of God" rather than for the paycheck or the praise. He treated every mundane task like a high-stakes ceremony.

👉 See also: The Gospel of Matthew: What Most People Get Wrong About the First Book of the New Testament

Why We Keep Getting It Wrong

We usually think meditation means "turning off" the world. You go into a dark room, close your eyes, and try to escape the noise. Lawrence did the exact opposite. He turned the noise into the meditation.

The Brother Lawrence practice of the presence of God isn't about ignoring your chores; it's about doing them with a specific kind of internal posture. He didn't use a bunch of methods. In fact, he kind of hated methods. He tried them when he first entered the monastery—all the structured stuff the other monks were doing—and it just made him miserable. He felt like he was failing at being "holy."

So he quit.

He decided to just... be there. He realized that God doesn't need us to be "good" at praying; He just wants us to be present.

There's a specific nuance here that people miss: Lawrence didn't just "think" about God. He related to Him. It was personal. He’d screw up, he’d get frustrated, and he’d just tell God, "Well, I can’t do any better than this if You leave me to myself." Then he’d move on. No self-flagellation. No guilt trips. Just a quick course correction and back to the task.

The Problem With Modern "Mindfulness" vs. Lawrence

Today, we talk about "flow states." We talk about being "present in the moment." But Lawrence’s approach has a different flavor because it has an object.

Mindfulness is often about the self—observing your own thoughts, calming your own nervous system. It’s useful, sure. But for Lawrence, the Brother Lawrence practice of the presence of God was about an "other." It wasn't just about being present; it was about being present to Someone. This shifted the burden off his own shoulders. He wasn't trying to achieve a state of Zen; he was just hanging out with a Friend.

✨ Don't miss: God Willing and the Creek Don't Rise: The True Story Behind the Phrase Most People Get Wrong

How to Actually Do This Without Joining a Monastery

You’re probably not a 17th-century monk. You have Slack notifications, a mortgage, and a car that’s making a weird clicking sound.

How does this work in a 2026 lifestyle?

First, stop waiting for the "perfect" time to be spiritual. If you can’t find God while you’re checking your email, you’re probably not going to find Him in a 10-minute meditation at 6:00 AM either. The Brother Lawrence practice of the presence of God starts by acknowledging that the "boring" parts of your life are actually the primary venue for your spiritual growth.

The "Check-In" Method. Lawrence didn't spend hours in deep contemplation. He spent seconds, hundreds of times a day. When you're walking to the kitchen to get more coffee, just do a three-second internal acknowledgement. "I'm here, You're here. Let's do this."

The End of Grumbling. Lawrence was big on doing things "for the love of God." If you’re scrubbing a toilet, and you’re doing it with a resentful heart, you’re missing the presence. He believed that if you offer the mundane task as a gift, the task itself changes. It becomes a prayer.

Rejection of "Spiritual Success." This is huge. Lawrence didn't care about feeling "peaceful." Some days he felt nothing. Some days he felt terrible. He didn't let his feelings dictate the practice. He just stayed at it.

Honestly, it’s a lot like training a puppy. Your mind is going to run away. It’s going to go to your grocery list or that embarrassing thing you said in 2014. When it does, you don't beat the puppy. You just pick it up and put it back on the mat.

🔗 Read more: Kiko Japanese Restaurant Plantation: Why This Local Spot Still Wins the Sushi Game

Real-World Evidence: Does This Stuff Work?

While Lawrence was a mystic, modern psychology is finally catching up to his "clumsy" wisdom. Dr. Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi’s work on "Flow" echoes Lawrence’s focus on the task at hand. When we are fully immersed in an activity, our ego drops away. Lawrence just added a theological dimension to that ego-loss.

Furthermore, the "Acceptance and Commitment Therapy" (ACT) model used by many therapists today mirrors Lawrence's approach to failure. Instead of fighting intrusive thoughts or feeling guilty for being distracted, you simply note the distraction and return to your values. Lawrence was doing "defusion" (separating yourself from your thoughts) three hundred years before it had a clinical name.

A Quick Word on the "Letters"

If you actually read the letters, you’ll see he was kind of a sassy guy. He wrote to a woman who was complaining about her health, telling her basically that suffering is a gift if you use it to stay close to God. It sounds harsh, but he lived it. He had chronic pain in his legs for years and never complained. He just used the pain as another "bell" to remind him to check back into the Presence.

Actionable Steps for the Next 24 Hours

If you want to try the Brother Lawrence practice of the presence of God, don't start by trying to do it all day. You will fail. You'll forget within five minutes.

Instead, pick one "trigger" activity.

Maybe it’s when you’re washing the dishes. Or when you’re waiting for a Zoom call to start. For that specific five minutes, decide that this task is your "chapel." Don't rush through it to get to the "important" stuff. The task is the important stuff.

- Step 1: The Interior Glance. Every time you start a new task today, take one breath and internally acknowledge that you aren't doing it alone.

- Step 2: The Offering. Before you open your laptop, say (internally or out loud), "I'm doing this for You." It sounds cheesy, but it shifts your brain out of "survival mode" and into "service mode."

- Step 3: The Gentle Return. When you realize you've been doom-scrolling or worrying for the last twenty minutes, don't apologize. Don't get mad at yourself. Just "glance" back.

Lawrence proved that a life of "deep" spirituality doesn't require a special robe or a vow of silence. It just requires a little bit of attention paid to the ordinary. He found the "pearl of great price" in a sink full of dirty dishes. You can probably find it in your cubicle or your car, too.