You know that feeling when a riddle is right on the tip of your tongue, but your brain just decides to go on vacation? It’s annoying. Actually, it’s more than annoying—it’s a specific kind of cognitive friction that happens when our autopilot thinking crashes into a logic wall. We’ve all been there, staring at a list of brain teasing questions with answers and feeling slightly humbled when the solution is so simple it hurts.

Brains are lazy. Honestly, they’re designed to be. Evolutionarily speaking, your gray matter wants to conserve energy by using "heuristics," which are basically mental shortcuts. When you see a problem, your brain tries to match it to a pattern it already knows. But brain teasers are specifically engineered to exploit those shortcuts. They lead you down a sunny path and then suddenly turn into a brick wall.

Why We Fall for the Same Old Tricks

Psychologists often talk about "functional fixedness." This is the mental block that prevents you from seeing an object or a concept as anything other than its traditional use. If I give you a box of thumbtacks and a candle, you might struggle to realize the box itself can be part of the solution.

Take this classic: What has keys but can't open a single lock? Your brain immediately scans for physical keys—house keys, car keys, maybe those tiny ones for diaries. You’re stuck in the "lock and key" schema. It takes a second for the "musical" or "typing" schema to override the physical one. The answer, obviously, is a piano. Or a keyboard. It’s simple, yet for a split second, your neurons were firing in the wrong zip code.

The Science of the "Aha!" Moment

There is actually a rush of dopamine when you finally crack one of these. Dr. John Kounios at Drexel University has spent years studying the "Aha!" moment using EEG and fMRI scans. He found a burst of high-frequency gamma-band activity in the right temporal lobe right before someone solves a riddle.

It’s a literal spark.

This isn't just about trivia. It’s about cognitive flexibility. People who regularly engage with brain teasing questions with answers tend to be better at divergent thinking. They don't just look for the "right" answer; they look for all possible interpretations of the prompt.

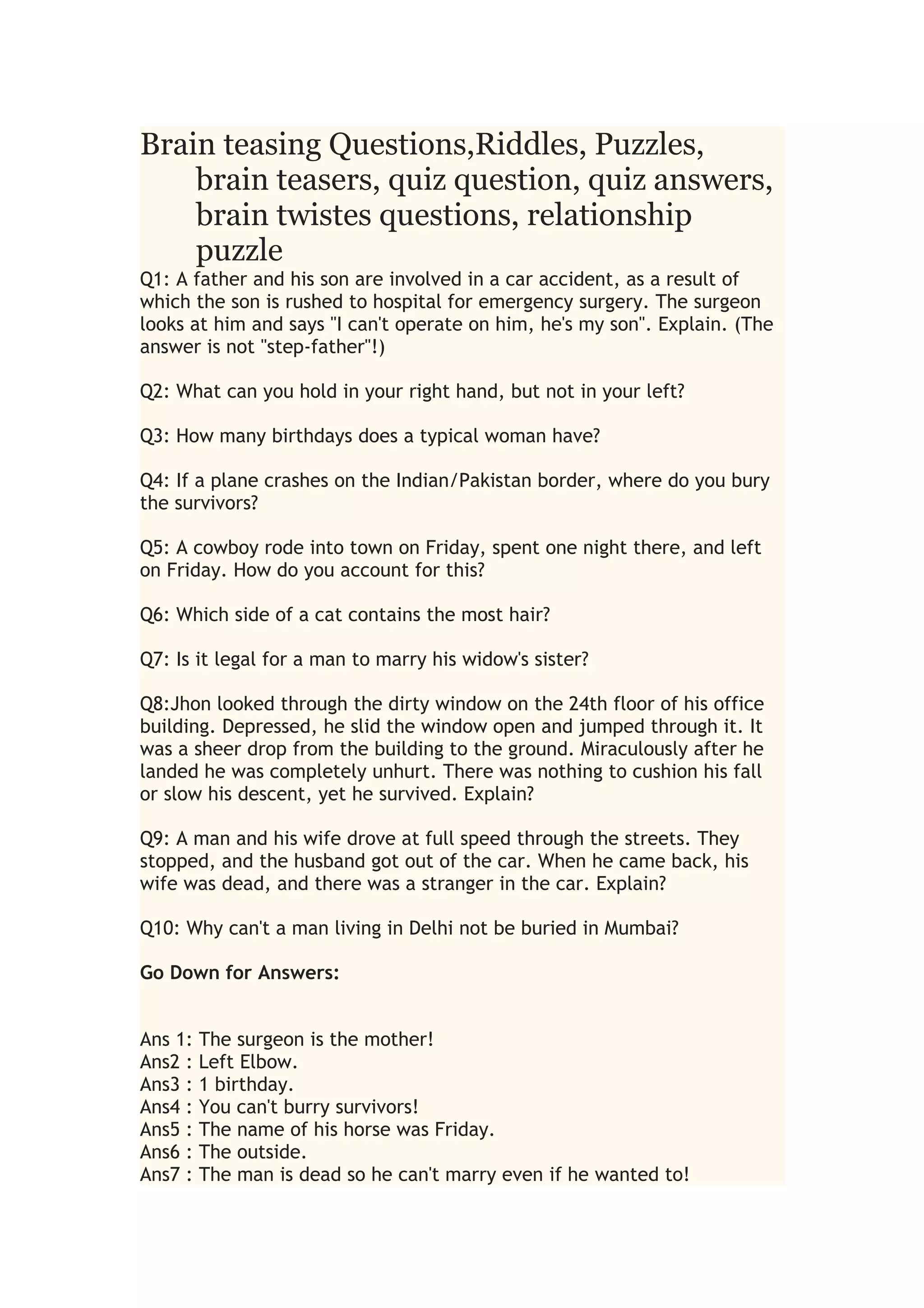

Some Brain Teasing Questions With Answers to Test Your Flexibility

Let's get into the thick of it. I've gathered some that range from "I should have known that" to "wait, let me read that again."

✨ Don't miss: Green Emerald Day Massage: Why Your Body Actually Needs This Specific Therapy

The Heavy Lifter

The Question: Which is heavier: a ton of bricks or a ton of feathers?

The Reality: Most people want to say bricks because they’re dense. But a ton is a ton. They weigh exactly the same. This is a classic example of your brain ignoring the units because it’s too focused on the material properties.

The Family Tree

The Question: A girl has as many brothers as she has sisters, but each boy has only half as many brothers as sisters. How many brothers and sisters are there?

The Solution: This one usually requires a pen and paper for most of us. There are four sisters and three brothers. If you’re a girl in that group, you have three sisters and three brothers (equal). If you’re a boy, you have two brothers and four sisters (half).

The Silent Killer

The Question: What is so fragile that saying its name breaks it?

The Solution: Silence.

The Lateral Thinking Trap

Lateral thinking is a term coined by Edward de Bono in 1967. It’s about solving problems through an indirect and creative approach, typically through viewing the problem in a new and unusual light.

Consider the "Man in the Elevator" riddle. A man lives on the tenth floor of a building. Every day he takes the elevator to go down to the ground floor to go to work or out shopping. When he returns, he takes the elevator to the seventh floor and then walks up the stairs to reach his apartment on the tenth floor. He hates walking, so why does he do it?

If you think logically about elevator mechanics, you'll never get it. You have to think about the man.

The answer? He’s a person of short stature. He can’t reach the button for the tenth floor. On rainy days, he uses his umbrella to hit the button, so he can go all the way up.

🔗 Read more: The Recipe Marble Pound Cake Secrets Professional Bakers Don't Usually Share

It’s kinda brilliant because the solution has nothing to do with the elevator and everything to do with a detail we weren't given but had to infer. That’s the core of high-level brain teasing.

Why Your Age Changes How You Solve These

Interestingly, kids often solve certain brain teasers faster than adults.

Why? Because they haven't spent decades reinforcing those mental shortcuts I mentioned earlier. An adult sees a picture of a bus and starts thinking about traffic, taxes, and their commute. A child looks at the bus and notices which way the door is facing.

There’s a famous riddle involving a bus where you have to guess which direction it’s traveling. Because the drawing doesn't show a door, kids in the UK or US (where buses drive on specific sides) immediately know it’s moving away from the side where the door should be. Adults overthink the physics; kids just look at what’s missing.

The Real-World Benefit of Mental Gymnastics

Is this all just for fun at parties? Not really.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, companies like Google and Microsoft famously used brain teasing questions with answers in their job interviews. They’d ask things like, "Why are manhole covers round?"

(The answer, by the way, is so they can't fall through the hole. A square cover could be tilted diagonally and dropped down.)

💡 You might also like: Why the Man Black Hair Blue Eyes Combo is So Rare (and the Genetics Behind It)

While many tech firms have moved away from these "guesstimation" or riddle-based interviews in favor of practical coding tests, the underlying logic remains. They wanted to see how you handle being stuck. Do you panic? Or do you start asking clarifying questions?

Working through these problems trains you to sit with discomfort. In a world of instant gratification and Google at our fingertips, being "stuck" is a rare and valuable state of mind. It forces the prefrontal cortex to work overtime.

Improving Your Creative Problem-Solving

If you want to get better at this, you have to stop trying to be "right" immediately.

- Question the Premise. If a riddle says "a man walks into a bar," don't assume it's a place that serves drinks. It could be a literal metal bar.

- Visualize the Scene. If the teaser involves movement or physical objects, try to build a 3D model in your head.

- Say it Out Loud. Sometimes the way a word sounds is the clue. "The word 'and' appears once in this sentence." Sometimes phonetic clues are hidden in plain sight.

Final Thoughts on Cognitive Play

Solving brain teasers isn't about being a genius. It’s about being curious enough to look past the obvious. We spend so much of our lives on autopilot—scrolling, driving, working—that we forget how to actually think about the mechanics of a problem.

Next time you hit a wall with a riddle, don't jump straight to the answer. Sit with that feeling of being stumped. That's actually your brain expanding its boundaries.

To keep your mind sharp, try to incorporate a few minutes of "divergent thinking" every day. Take a common object, like a paperclip, and try to come up with 10 uses for it that aren't holding paper. It’s the same muscle you use when solving the most complex riddles.

Actionable Steps for Sharp Thinking:

- Diversify your puzzles: Don't just do Sudoku. Mix in lateral thinking riddles, spatial puzzles, and wordplay to engage different brain regions.

- Teach others: Explaining the logic behind a solution to someone else reinforces the neural pathways associated with that type of reasoning.

- Limit your "Search Time": When you encounter a problem, give yourself at least 5 minutes of focused "struggle" before looking up the answer. The growth happens in the struggle, not the reveal.

- Read more fiction: Studies suggest that reading complex narratives improves "theory of mind" and the ability to see situations from multiple perspectives, which is a key component of solving riddles.