Let's be real for a second. Most people look at a box and whisker plot graph and their brain just shorts out. It looks like a rectangle with two antennas glued to the ends, and if you haven't looked at one since 10th-grade stats, you’ve probably forgotten what the heck it’s actually telling you. But here's the thing: if you're dealing with a massive pile of data and you just look at the "average," you're probably lying to yourself.

Averages are dangerous. They hide the messy truth.

If you have ten people in a room and one of them is Elon Musk, the "average" net worth in that room is billions of dollars. That tells you absolutely nothing about the other nine people who are probably wondering how they're going to pay rent. This is exactly why the box and whisker plot—or the "boxplot" if you're into the whole brevity thing—is the unsung hero of data visualization. It doesn't just show you the middle; it shows you the spread, the outliers, and the weird stuff happening at the edges.

What’s Actually Happening Inside the Box?

John Tukey. That’s the name you need to know. He’s the guy who introduced this back in 1970. He wanted a way to visualize the "Five-Number Summary" without making people read a boring table.

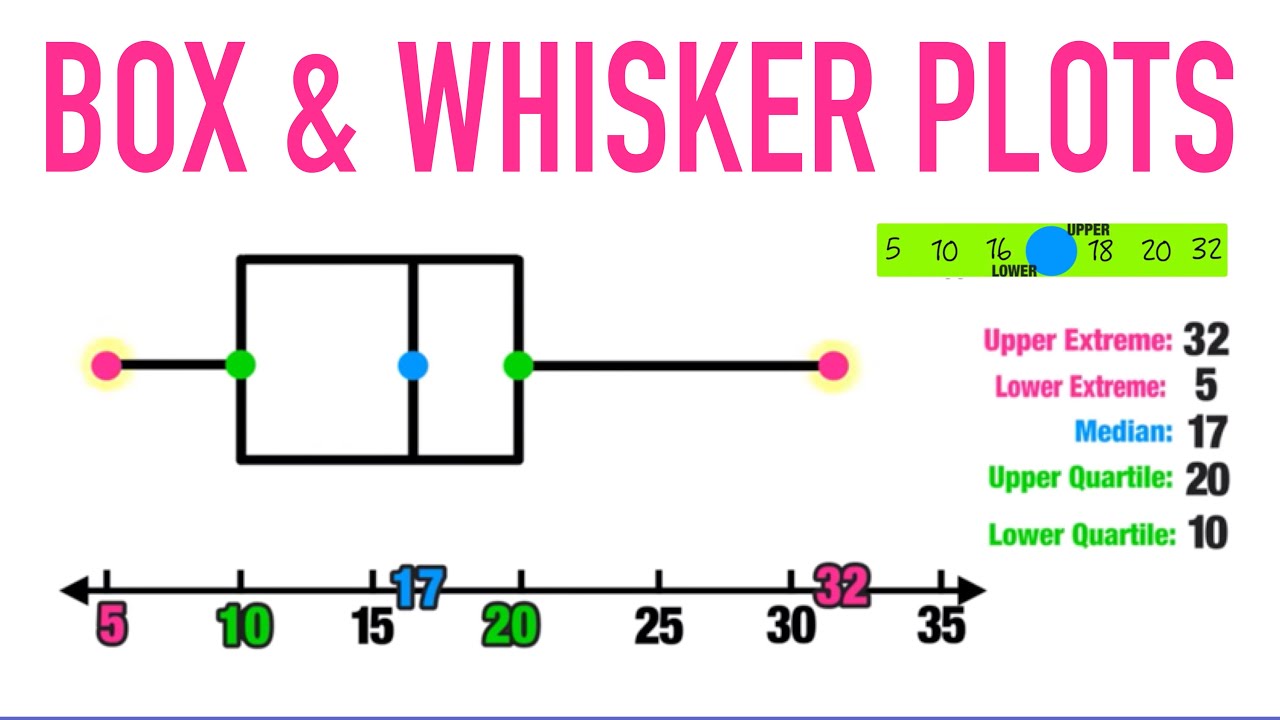

Think of it as a snapshot of a distribution. You’ve got the minimum value, the first quartile (Q1), the median, the third quartile (Q3), and the maximum value. Basically, the box represents the middle $50%$ of your data. If that box is tiny, your data is consistent. If it’s stretched out like a piece of saltwater taffy, your data is all over the place.

The line inside the box? That’s the median. It’s the literal middle point. Half the numbers are higher, half are lower.

✨ Don't miss: US Space Force Ships: What the Military Actually Flies in Orbit

Honestly, the median is way more honest than the mean (the average). If you’re looking at house prices in a neighborhood, one $10 million mansion will skyrocket the average, but it won't budge the median much. The boxplot protects you from being fooled by that one outlier.

Those "Whiskers" and the Mystery of Outliers

Then you have the whiskers. They extend from the box to show the range of the rest of the data. Usually, they represent everything within 1.5 times the Interquartile Range (IQR).

Wait, IQR? It sounds like math homework, but it’s just the height of the box.

$IQR = Q3 - Q1$

If a data point is way outside those whiskers, it gets its own little dot or asterisk. That’s an outlier. In the world of tech or manufacturing, those dots are the most important part of the whole graph. They’re the "Why did this server crash?" or "Why did this batch of batteries explode?" points. Without the box and whisker plot graph, those anomalies might just get folded into a "standard deviation" and forgotten until they cause a real problem.

Why Excel and Google Sheets Kinda Struggle with This

For years, making these was a nightmare in standard spreadsheet software. You had to hack the system using stacked bar charts and invisible error bars. It was a mess.

Now, Microsoft and Google have built-in boxplot options, but they're still a bit clunky. If you're serious about this, you're probably using R (the ggplot2 library is the gold standard here) or Python with Seaborn or Matplotlib.

import seaborn as sns

sns.boxplot(x='category', y='value', data=df)

That tiny bit of code does more for your data clarity than a thousand-row spreadsheet ever could. It lets you compare different groups side-by-side. Imagine you’re testing website load times on Chrome vs. Safari vs. Firefox. A bar chart would show you three bars of roughly the same height. Boring. A boxplot might show you that while the median time is the same, Firefox has a massive "whisker" of slow load times that's driving users crazy.

[Image comparing multiple box plots side-by-side for different categories]

The "Notched" Variation Nobody Talks About

If you see a boxplot that looks like someone took a bite out of the sides, that’s a "notched" boxplot. It’s not just for aesthetics. Those notches represent a confidence interval around the median.

If the notches of two different boxes don't overlap, there’s a "strong likelihood" that their medians are actually different. It’s a quick-and-dirty way to do a significance test without running a full T-test or ANOVA. It’s the kind of detail that makes you look like a wizard in a boardroom full of people who are just looking for the biggest bar on a chart.

✨ Don't miss: Bismuth and Bitcoin: Why These Two Oddities Actually Belong Together

Where This Fails (Because Nothing is Perfect)

I’ll be the first to admit it: boxplots can be deceptive.

They hide the "shape" of the data inside the quartiles. You could have a "bimodal" distribution—where the data has two big humps, like a camel—and a boxplot would make it look like one solid block of data. It smooths over the nuances.

This is why "Violin Plots" have become so popular lately. They take the boxplot and wrap it in a frequency curve. It gives you the best of both worlds: the structure of the box and the "vibe" of the distribution. But even then, for a quick executive summary, the box and whisker plot graph is still king because it doesn't require a degree in statistics to squint at and understand the basics.

Real World Example: The Healthcare Efficiency Study

Let's look at a real study. Dr. Mary Dixon-Woods has done extensive work on using data visualization in healthcare quality improvement. In one study, researchers used boxplots to track the "time to antibiotics" for patients with sepsis.

A simple average was useless. What they needed to see was the "tail"—the patients who were waiting 6 or 8 hours. By plotting these as whiskers and outliers, hospitals could see exactly which shifts or departments were failing to meet the "Golden Hour" standard. The boxplot didn't just provide data; it provided a target for saving lives.

How to Build a Better One Right Now

If you're about to make one of these for a report, stop and think about your audience.

- Labels are everything. Don't just put "Group A." Explain what Group A is.

- Color matters. Use contrasting colors if you're comparing groups.

- Don't hide the dots. Sometimes, if you have a small dataset, it’s better to overlay the actual raw data points on top of the boxplot. It’s called a "jitter" plot, and it prevents the box from hiding the fact that you only have five data points.

Putting the Boxplot to Work

You've got the theory. Now you need the execution. Don't just use this for "work" data. Use it for your life. Track your sleep patterns. Track your spending. If you look at your monthly spending as a boxplot, you’ll quickly see that your "average" grocery bill is fine, but those "outlier" weekend trips to Target are what's actually killing your savings account.

The box and whisker plot graph is about seeing the whole truth, not just the convenient part in the middle.

Your Next Steps:

- Audit your current reporting. Look at any bar chart showing an "average" and ask: "What is the range here?"

- Try a Jitter. If you use Python or R, add

geom_jitter()orstripplotover your boxplot to see if the box is hiding a weird distribution. - Define your Outliers. Decide now what a "bad" outlier looks like for your business—is it $1.5 \times IQR$, or do you need a stricter $3 \times$ threshold for extreme cases?

- Simplify for your boss. If you're presenting this to someone non-technical, literally draw an arrow to the median and write "The Middle" and an arrow to the outliers and write "The Problems."