You’ve probably heard it on a rainy Tuesday and felt that specific, hollow ache in your chest. Boots of Spanish Leather isn't just a folk song. Honestly, it’s a slow-motion car crash of a relationship, captured in nine perfect stanzas on Bob Dylan’s 1964 album, The Times They Are a-Changin'.

Most people think it’s a sweet, seafaring ballad. It isn't. Not really.

It’s actually a brutal masterclass in realization. You’re listening to a man figure out he’s being dumped in real-time through the mail. While the title sounds romantic—almost exotic—the "boots" themselves are a consolation prize for a broken heart.

The Real Story Behind the Song

To understand why this track hits so hard, you have to look at Suze Rotolo.

She was Dylan’s "muse" during his early Greenwich Village days. You know her—she’s the one huddled against him on the cover of The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan. In 1962, she headed off to Perugia, Italy, to study art. Dylan didn't want her to go. He was, by most accounts, pretty possessive.

The distance didn't just create a gap in miles; it created a gap in their shared reality.

While Suze was finding herself in Europe, Dylan was sitting in New York, writing songs like "Tomorrow Is a Long Time" and "Don't Think Twice, It's All Right." Boots of Spanish Leather was born from this period of agonizing wait.

The song is structured as a dialogue. It’s a series of letters.

She starts by asking what he wants from across the sea. He plays the romantic hero, saying he doesn't want silver or gold—he just wants her back "unspoiled." It’s a heavy word, "unspoiled." It reeks of the anxiety of a man worried his partner is changing without him.

💡 You might also like: Not the Nine O'Clock News: Why the Satirical Giant Still Matters

The Scarborough Fair Connection

If the melody sounds familiar, there’s a reason. Dylan was a sponge.

In late 1962, he took his first trip to London. While he was there, he met a folk singer named Martin Carthy. Carthy taught him a specific arrangement of a traditional English ballad called "Scarborough Fair."

Dylan basically lifted that melody twice.

- First, for "Girl from the North Country."

- Then, for Boots of Spanish Leather.

They’re sister songs. Some fans argue that "Boots" is actually the superior version because it’s more narratively complex. While "Girl from the North Country" is a wistful memory of a past love, "Boots" is the actual moment the love dies.

It’s fascinating because Paul Simon would later make "Scarborough Fair" a global hit, but Dylan got there first, stripping the melody down to its barest, loneliest essentials.

Why the Boots?

The turning point of the song is devastating.

She sends a letter saying she doesn't know when she’s coming back. It "depends on how I’m a-feeling." That’s the death knell. Every person who has ever been ghosted or "slow-faded" knows that feeling.

Suddenly, Dylan’s narrator stops being the poetic lover.

📖 Related: New Movies in Theatre: What Most People Get Wrong About This Month's Picks

He realizes she’s gone. Not just across the ocean, but gone from the relationship. So, he gives up. He says, fine, if you’re not coming back, send me the boots.

The Irony of the Gift

There’s a theory in Dylan circles—and it’s a good one—that the request for "Spanish boots of Spanish leather" is a bit of a middle finger.

Earlier in the song, he rejected silver and gold. He was above material things. But once the love is dead, he asks for something expensive, functional, and durable.

"Yes, draw myself away from your ship-a-sailing / And yes, I'll take those boots of Spanish leather."

It’s almost like he’s saying, "If I can't have your heart, I’ll at least take a high-end souvenir." Some even point out that "Spanish boots" were historical torture devices, suggesting he’s asking her to send him the physical manifestation of the pain she’s already causing him.

Technical Mastery in Simplicity

Dylan recorded this on August 7, 1963.

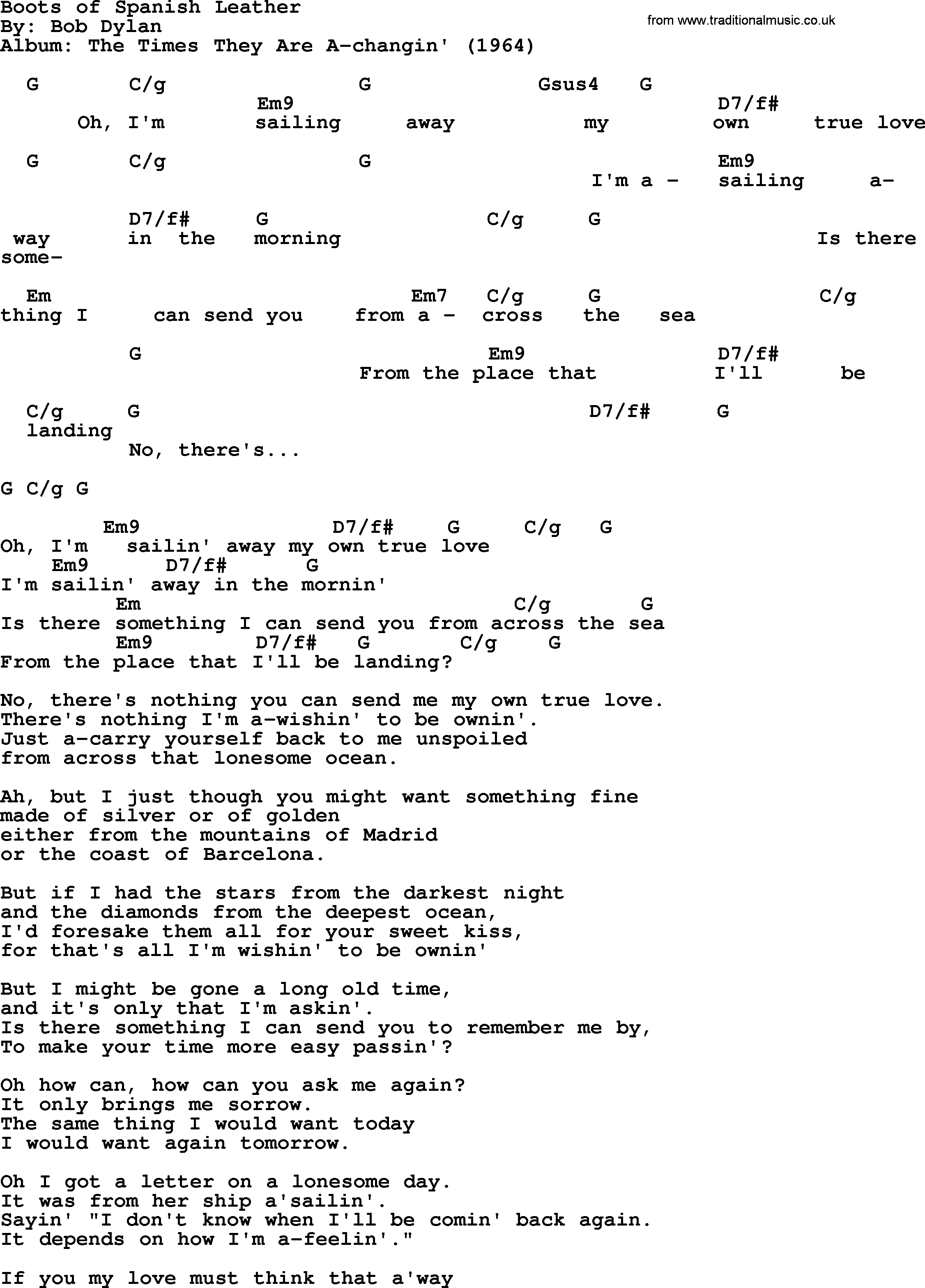

It’s just him, an acoustic guitar, and a harmonica he barely uses. The fingerpicking is steady, almost hypnotic. It mimics the rhythm of the waves or the steady ticking of a clock while waiting for a letter.

He uses "assonance" constantly—the repeating "-in'" sounds (sailin', mornin', landin'). It gives the song a folk authenticity that makes it feel hundreds of years old, even though he wrote it in a New York apartment.

👉 See also: A Simple Favor Blake Lively: Why Emily Nelson Is Still the Ultimate Screen Mystery

Key Differences: "Boots" vs. "North Country"

While the chords are nearly identical (usually played with a capo on the 2nd or 3rd fret), the delivery is different.

- Girl from the North Country is warm. It’s a "remember her to me" vibe.

- Boots of Spanish Leather is cold. It ends in a place of resignation and bitterness.

One is about a girl he used to know; the other is about a girl who is currently leaving him.

How to Truly Appreciate the Track

If you want to get the most out of this song, don't just stream it.

Find a lyric sheet. Follow the "voices." Notice how the first six stanzas are a back-and-forth, but the last three are all him. She has stopped writing. He is talking to a ghost.

It’s a song about the exact moment you realize you are no longer a "we."

Actionable Insights for Dylan Fans

- Listen to the Witmark Demos: There’s an early version where the melody is even more similar to "Scarborough Fair." It shows his process of refining the tune.

- Read Suze Rotolo’s Memoir: It’s called A Freewheelin' Time. She gives her side of the story, and it adds a layer of reality to the "muse" trope that Dylan often hid behind.

- Compare the Covers: Check out Nanci Griffith’s version or Mandolin Orange. They highlight the "dialogue" aspect by using male and female vocals, which makes the ending even more heartbreaking when one voice drops out.

The song remains a staple because it captures a universal truth. People leave. Sometimes they leave for a different country, and sometimes they just leave the person they used to be. The boots are just what’s left behind when the romance is gone.

Listen for the silence between the last few notes. That’s where the real story lives.

Next Steps: You can explore the rest of The Times They Are a-Changin' to see how Dylan balanced these intensely personal songs with his famous protest anthems like "The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll."