Honestly, if you grew up in a UK classroom anytime in the last forty years, you probably think you know exactly what books written by michael morpurgo are all about. You’re thinking: "Oh, the horse one." Or maybe "The one with the island and the old Japanese guy."

But there is a specific kind of magic—and a fair bit of grit—in his bibliography that people often overlook. Morpurgo isn’t just a "children’s author" in the way we usually mean it. He’s more like a war correspondent who happened to choose a younger audience because they're the only ones who still listen with their hearts.

Why We Keep Coming Back to Joey and Charlie

It is impossible to talk about his work without starting with War Horse. Published back in 1982, it didn't actually set the world on fire immediately. It was a slow burn. Most people forget that it took a National Theatre production with giant puppets and a Spielberg movie to turn Joey into a global icon.

✨ Don't miss: Boruto Blue Vortex 18: Why the Power Balance Just Shifted Forever

But why does it work?

Basically, it's the perspective. Writing from the point of view of the horse wasn't just a gimmick. It was a way to show the utter pointlessness of the Great War without getting bogged down in human politics. Joey doesn't care about borders. He cares about oats and the boy who raised him.

Then you’ve got Private Peaceful. If you want to talk about books that absolutely wreck readers, this is the one. It’s set over twenty-four hours. One night. That's it. Tommo Peaceful is looking back on his life while waiting for the dawn, and the "twist" (if you can call a historical injustice a twist) regarding his brother Charlie is something that still sparks heated debates in school libraries. It’s a book about the "shot at dawn" soldiers, and it’s unapologetically angry about how they were treated.

The "Animal" Misconception

People often say, "Oh, he just writes about animals."

Well, yeah, he does. But look closer. In The Butterfly Lion, the lion isn't just a pet; it's a symbol of a lost childhood in South Africa and the enduring nature of a promise. In Kensuke's Kingdom, the orangutans are the bridge between a shipwrecked boy and an old man who has chosen to disappear from a world that dropped an atomic bomb on his family.

Morpurgo uses animals as "emotional anchors." He’s mentioned in interviews that animals provide a way into difficult conversations about loneliness, disability, and environmental collapse.

- Shadow: Follows a spaniel in Afghanistan and a boy in an asylum detention center.

- Running Wild: Uses a tsunami and an elephant to discuss the palm oil crisis.

- A Medal for Leroy: Uses a dog to peel back the layers of a family secret involving the first Black officer in the British Army.

More Than Just History Lessons

There is a weirdly common idea that books written by michael morpurgo are strictly historical fiction. That’s just not true. While he’s clearly obsessed with the World Wars—partly because he was a "war baby" born in 1943—he dips his toes into folklore and modern-day crises more than he gets credit for.

Take Why the Whales Came. It feels like a myth, but it’s rooted in the very real, very isolated culture of the Isles of Scilly. Or his retellings of Beowulf and Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. He strips away the stuffy, academic language of the original texts and turns them into what they were always meant to be: campfire stories.

And let’s talk about the "Dreamtime."

That's what he calls his process. He doesn't sit down and outline a plot with 3x5 index cards. He wanders around his farm in Devon. He milks cows. He mucks out sheds. He lets the story "compost" in his head for months before he ever puts pen to paper. Actually, he literally writes by hand, sitting on his bed, propped up by pillows. It's a very physical, old-school way of creating.

The Impact of "Farms for City Children"

You can’t really separate the books from the man’s life work. In 1976, Michael and his wife Clare started Farms for City Children.

They’ve had nearly 100,000 kids stay on their farms. Think about that. These are kids who might have never seen a cow in real life. When you read a Morpurgo book and the description of the mud, the smell of the hay, or the cold wind feels "too real," it’s because he’s spent forty years watching children react to those exact things.

🔗 Read more: Why the John Williams Jurassic Park soundtrack Still Gives Us Goosebumps

He isn't guessing how a ten-year-old feels when they see a birth or a death on a farm. He’s seen it.

What to Read Next: A Quick Roadmap

If you’ve already done the "Big Three" (War Horse, Private Peaceful, Kensuke’s Kingdom), where do you go?

- For something heart-wrenching: Alone on a Wide Wide Sea. It deals with the British child migrant schemes—kids sent to Australia after WWII thinking they were going on an adventure, only to face horrific conditions.

- For something shorter: The Mozart Question. It’s a slim volume about a famous violinist and a secret hidden in the Holocaust. It's beautiful and devastating.

- For the younger crowd: The Mudpuddle Farm series. It’s light, funny, and shows his range beyond the "heavy" stuff.

- For the hidden gem: Mr. Skip. It’s a bit more whimsical, involving a garden gnome and a girl who wants to be a jockey.

How to Get the Most Out of Morpurgo’s Catalog

If you're an educator or a parent, the worst thing you can do is treat these as "test prep" books. They are designed to be read aloud. Morpurgo started as a teacher who realized his students were bored by the books on the curriculum, so he started making up stories at the end of the day to keep them quiet.

The rhythm of his prose is oral. It's meant for the ear.

Actionable Next Steps:

- Try the Audiobooks: Many are narrated by Morpurgo himself. His voice has this gentle, gravelly quality that makes the stories feel like a grandfather telling you a secret.

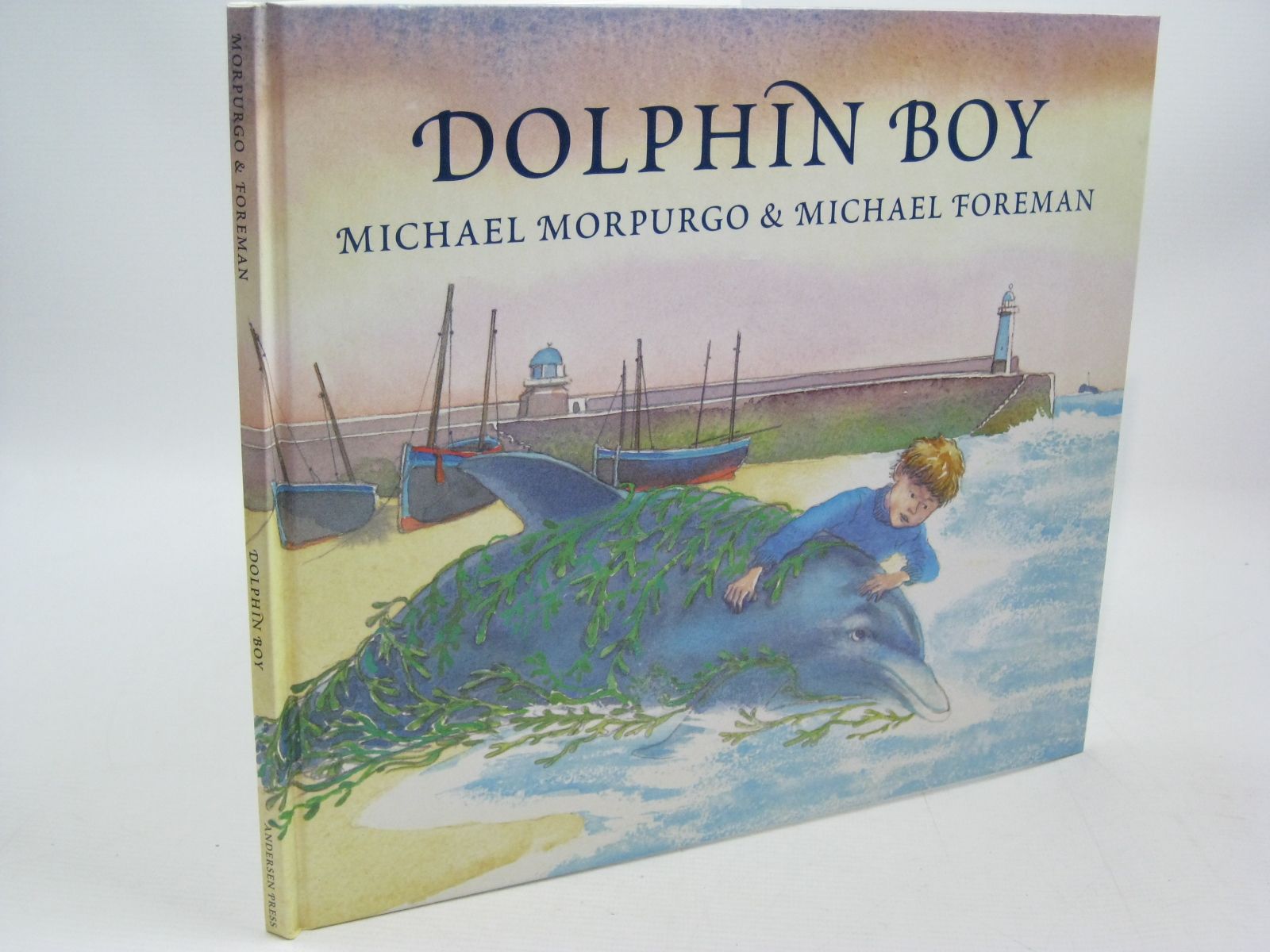

- Look for the Illustrators: His long-term collaboration with Michael Foreman is legendary. The soft watercolors in books like Kaspar: Prince of Cats add a layer of atmosphere that text alone can't reach.

- Visit the History: If a book is set in a specific place—like the Scilly Isles for Why the Whales Came or the French village in Waiting for Anya—look up the real history. He almost always bases his fiction on a "nugget" of truth he found in a local museum or a conversation with an elder.

Whether he’s writing about a cat on the Titanic or a boy in the trenches, the core of books written by michael morpurgo remains the same: a belief that we are defined by our kindness, especially when the world is at its loudest and most violent.