You’ve probably heard of the "Skinner Box." Or maybe you’ve seen that old footage of a pigeon playing ping-pong. Most people associate B.F. Skinner with cold, clinical laboratory experiments and the idea that we’re all just biological machines responding to rewards.

Honestly? That’s a massive oversimplification.

When you actually sit down with the books written by B.F. Skinner, you find something much weirder and more provocative than a simple manual for training rats. Skinner wasn't just a scientist; he was a social reformer, a novelist, and a philosopher who thought he could save the world.

He didn't just want to understand behavior. He wanted to design a culture.

The Book That Scared the Public: Beyond Freedom and Dignity

If you want to understand why Skinner became one of the most hated and admired men in America, you start with Beyond Freedom and Dignity (1971). This is the big one.

The title alone makes people's skin crawl.

Basically, Skinner argued that our traditional notions of "free will" and "moral responsibility" are outdated superstitions. He believed that if we keep clinging to the idea that people are "free" agents, we’ll never actually solve the big problems like war, overpopulation, or pollution.

Why? Because we'll keep blaming "human nature" instead of fixing the environment that creates the behavior.

He wasn't saying we shouldn't have freedom. He was saying that what we call freedom is usually just the absence of obvious punishment.

The reaction was explosive.

Vice wasn't a thing back then, but the 1970s equivalent of a "cancel culture" storm hit Skinner hard. He appeared on the cover of Time magazine with the headline "Skinner’s Utopia: Panacea or Path to Hell?" Critics called him a fascist. They said he wanted to turn humans into robots.

🔗 Read more: Finding the Right Word That Starts With AJ for Games and Everyday Writing

But if you read the text closely, you see a man frustrated by the slow pace of social change. He genuinely thought that a "technology of behavior" could make people kinder and more productive.

Walden Two: The Behaviorist Utopia

Long before he was a lightning rod for controversy, Skinner wrote a novel.

Walden Two (1948) is a strange piece of fiction. It’s about a group of people who start a communal society based on "behavioral engineering."

There are no jails. There are no politicians. Instead, children are raised by the community, and "planners" manage the environment to ensure everyone stays happy and motivated.

It sounds like a cult, right?

Many readers certainly thought so. But for Skinner, it was a thought experiment. He wanted to show how positive reinforcement could replace the "aversive control" (aka punishment and threats) that dominates modern life.

The book actually inspired real-life communities. Places like Twin Oaks in Virginia and Los Horcones in Mexico were directly influenced by the ideas in Walden Two.

Some of these places still exist.

They didn't all turn into "behaviorist dictatorships." Instead, they became experiments in cooperative living. It turns out that when you try to apply "books written by B.F. Skinner" to real humans, things get a lot messier than they are in a lab.

Science and Human Behavior: The Foundation

If Beyond Freedom and Dignity is the manifesto and Walden Two is the dream, then Science and Human Behavior (1953) is the textbook.

💡 You might also like: Is there actually a legal age to stay home alone? What parents need to know

This is where the heavy lifting happens.

Skinner takes the principles he discovered while working with animals—things like operant conditioning and schedules of reinforcement—and applies them to everything.

- Government

- Religion

- Psychotherapy

- Education

- Economics

He basically says: "Look, if we can predict how a pigeon will peck for grain, we can understand why a person votes, prays, or buys a certain brand of soap."

It’s a dense read.

But it’s also remarkably consistent. Skinner had this incredible ability to look at a complex social interaction and strip it down to the "contingencies of reinforcement." He didn't care about what people were thinking or feeling inside. He only cared about what they did and what happened right after they did it.

The Verbal Behavior Controversy

We can't talk about Skinner's books without mentioning Verbal Behavior (1957).

This was Skinner’s attempt to explain language through behaviorism. He spent over twenty years writing it. He thought it was his most important work.

Then Noam Chomsky happened.

Chomsky wrote a review of the book that became more famous than the book itself. He argued that Skinner’s model was fundamentally broken because it couldn't account for the "creativity" of language—how children can say things they’ve never heard before.

This "paradigm clash" basically gave birth to the Cognitive Revolution.

📖 Related: The Long Haired Russian Cat Explained: Why the Siberian is Basically a Living Legend

For decades, the narrative was that Chomsky "debunked" Skinner. But in recent years, behavior analysts have pushed back. They argue that Chomsky didn't actually understand Skinner’s technical definitions.

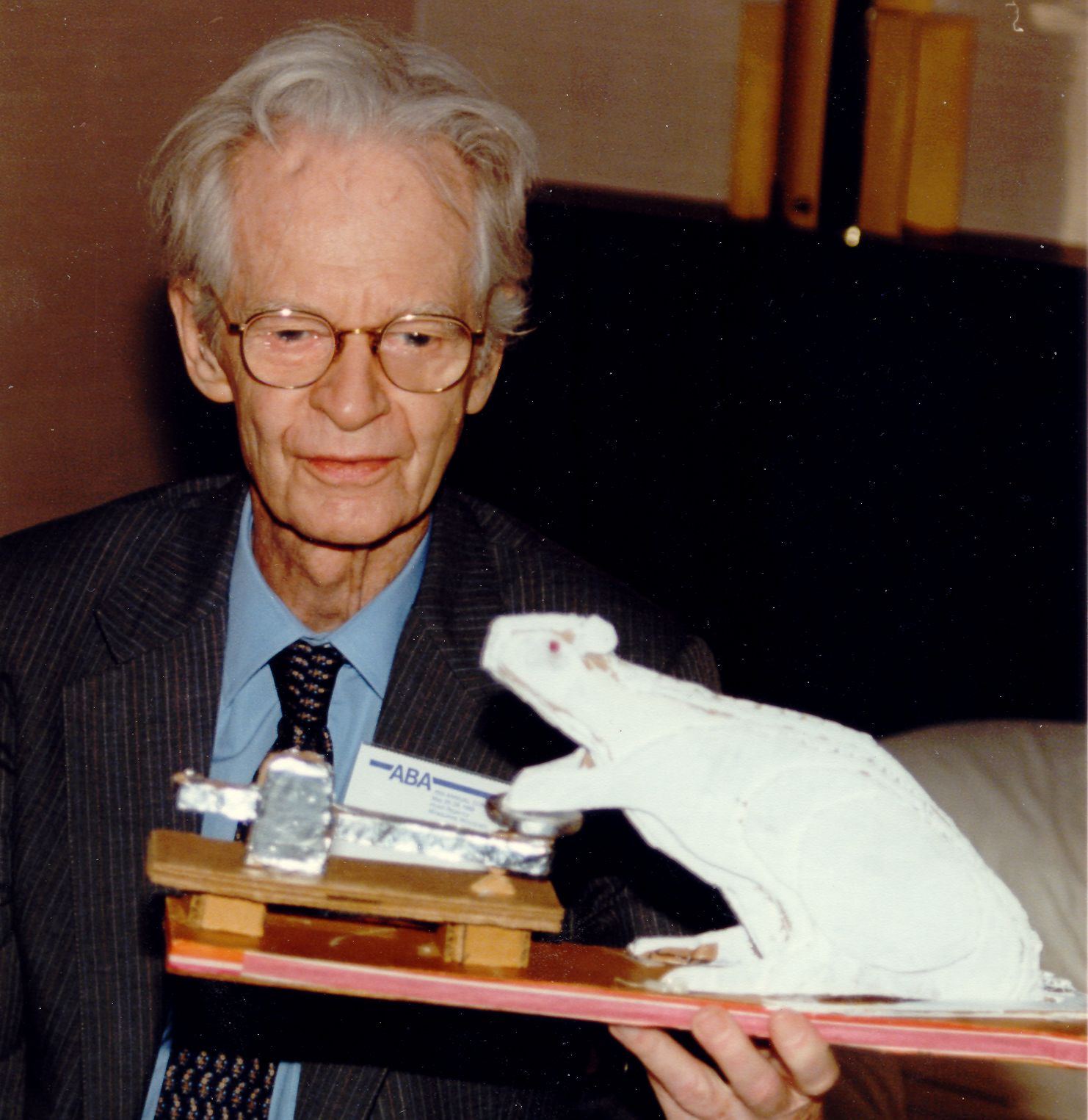

Whether you agree with him or not, Verbal Behavior is still the foundation for many modern autism therapies, like Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA).

The Surprising Relevance in 2026

It’s easy to dismiss Skinner as a relic of the mid-20th century.

We don't talk about "behavioral engineering" much these days. Or do we?

Look at your phone.

Every notification, every "like," every "streak" on a language app—that is Skinnerism in its purest form. Silicon Valley is essentially a giant Skinner box. The engineers at big tech companies have read their Skinner. They know exactly which "variable ratio schedule" will keep you scrolling for another twenty minutes.

We live in the world Skinner described, even if we don’t use his vocabulary.

He warned us that if we didn't take control of the environment, the environment would control us. In 2026, with algorithms shaping our political views and our spending habits, his warnings feel less like "mad scientist" ramblings and more like a prophecy.

Actionable Insights: How to Read Skinner Today

If you’re interested in diving into the books written by B.F. Skinner, don't just start at the beginning. It's a lot.

- Start with About Behaviorism (1974). It’s the most accessible entry point. Skinner wrote it specifically to answer his critics and explain his philosophy in plain English.

- Read Walden Two as a "What If?" Don't look at it as a perfect blueprint. Look at it as a challenge to the way we organize our own lives and families.

- Observe your own "Schedules of Reinforcement." Once you understand Skinner’s concepts, you’ll start seeing them everywhere. Why do you check your email when you’re bored? Why is it so hard to stop playing that one mobile game?

- Separate the Science from the Politics. You can find his data on reinforcement schedules incredibly useful for habit-building without agreeing with his views on "the death of the self."

Skinner’s legacy isn't about pigeons or boxes. It's a fundamental question: If we are products of our environment, shouldn't we be more careful about the environments we build?

To get the most out of Skinner's work, try mapping your own daily habits to his "four consequences" model: positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, positive punishment, and negative punishment. Identify one habit you want to change and consciously alter the immediate consequence that follows it.