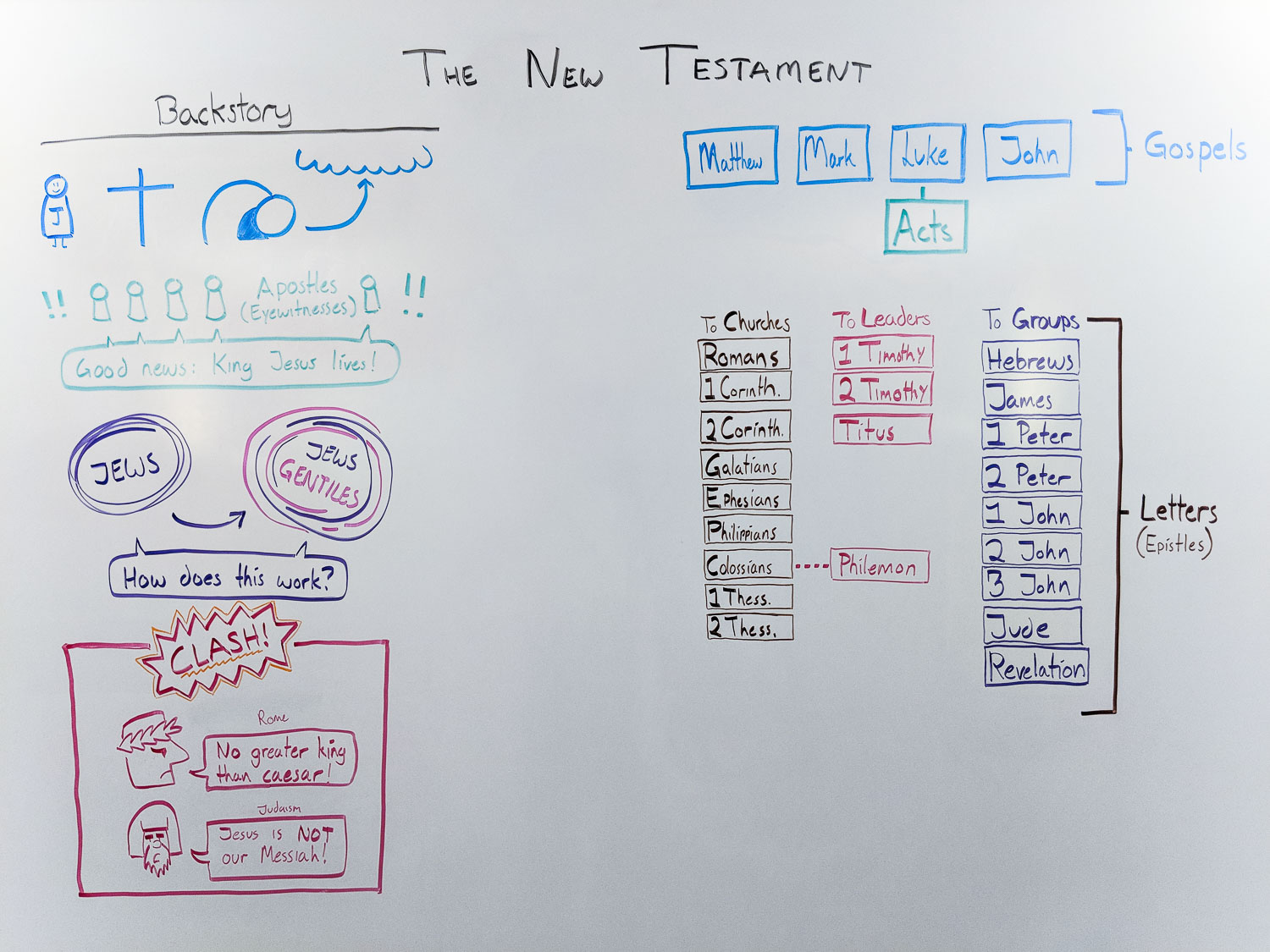

Ever tried reading the New Testament straight through? It’s a trip. You start with four different versions of the same story, then move into a history of the early church that reads like an action movie, followed by a bunch of letters that get really specific about 1st-century drama, and it all ends with a psychedelic vision of the world ending. Most people think they know the books of the New Testament because they’ve seen the movies or heard the sermons. But honestly, the way these 27 documents actually came together is way messier and more fascinating than the "perfectly curated" version we usually hear.

It isn't just a list. It’s a library.

Most folks assume the New Testament was written in the order you see it in your Bible. Nope. Not even close. If you want to read it chronologically, you’d actually start with 1 Thessalonians—a letter written by a guy named Paul who was basically stressed out about how a specific church in Greece was doing. The Gospels? Those came decades later. This matters because when we talk about the books of the New Testament, we’re looking at a collection of writings that took about 50 to 60 years to finish, written by people who didn't always agree on how to explain what they’d just witnessed.

Why the Order of the Books of the New Testament is So Weird

If you open a standard Bible, you see Matthew first. That’s because the early church thought Matthew was the oldest Gospel. Turns out, they were likely wrong. Most modern scholars, like the late Raymond Brown or the prolific N.T. Wright, agree that Mark was probably the "OG" Gospel. It’s shorter, punchier, and has a bit of a frantic energy to it.

So why is Matthew first? It’s basically a bridge. Matthew is obsessed with the Old Testament, constantly quoting it to prove that Jesus was the guy the prophets were talking about. It makes for a smoother transition from Malachi. Then you get Mark, Luke, and John. These four aren't meant to be a single biography; they are four different portraits. Think of it like four different people describing a car crash from four different street corners. You’re going to get different details.

After the Gospels, you hit Acts. This is the only "history" book in the set. It’s a sequel to Luke. Then come the Epistles (mostly Paul’s letters), and they aren't organized by date. They’re organized by size. Romans is the longest, so it goes first. Philemon is tiny, so it’s near the end. It’s a weirdly bureaucratic way to organize sacred scripture, but it stuck.

🔗 Read more: Monroe Central High School Ohio: What Local Families Actually Need to Know

The Letters: Ancient Mail You Weren't Supposed to Read

Actually, that’s a bit of an exaggeration. You were supposed to read them, but they weren't written for us. They were written for specific groups of people in the Roman Empire who were trying to figure out how to live out this new faith without getting killed or sued.

Take the book of Galatians. Paul is fuming in that letter. He doesn't even start with his usual "I thank God for you" pleasantries. He basically jumps straight to "Who bewitched you?" He’s mad because people were trying to force new converts to get circumcised. It’s a raw, heated, 1st-century legal argument. When you read the books of the New Testament as a collection of real mail, the whole thing feels much more alive.

Then you have the "General Epistles." These are books like James, 1 and 2 Peter, 1, 2, and 3 John, and Jude. They aren't addressed to specific cities. They’re more like "To whom it may concern" circulars for the whole movement. James is famous for being the "practical" one. While Paul is talking about deep theology and grace, James is over in the corner saying, "If you don't help poor people, your faith is dead." Martin Luther famously hated the book of James. He called it an "epistle of straw" because it seemed to contradict Paul. It’s this internal tension that makes the New Testament so durable. It’s not a monolith; it’s a conversation.

The Mystery of Hebrews

Who wrote Hebrews? Nobody knows. Seriously. For a long time, people credited Paul, but the Greek is way too sophisticated for his style. It reads more like a sermon than a letter. It’s a brilliant, dense argument connecting Jewish temple rituals to the life of Jesus. It almost didn't make it into the final list of the books of the New Testament because of the authorship question.

That Wild Ending: Revelation

Revelation is the one that gets all the attention. It’s also the one most people get completely wrong. Most scholars, including experts like Elaine Pagels, point out that Revelation is "Apocalyptic Literature." This was a specific genre of writing back then—lots of symbols, numbers, and strange creatures used as a sort of "code" to talk about political oppression under the Roman Empire.

💡 You might also like: What Does a Stoner Mean? Why the Answer Is Changing in 2026

When John writes about a "Beast" with a specific number, he’s likely talking about the Emperor Nero. To the original readers, this wasn't a crystal ball about the year 2026; it was a survival manual for the year 95. It was a way of saying, "The world looks like a monster right now, but hang on, because something better is coming."

How Did This List Actually Get Finalized?

It wasn't like there was a single meeting where a group of guys in robes just picked their favorites. It was a slow, organic process that took centuries.

By the end of the 2nd century, most Christians were using the four Gospels and most of Paul’s letters. But there was a lot of debate about the fringes. Some people wanted the Shepherd of Hermas included. Others thought 2 Peter was a fake. The first time we see the exact list of 27 books of the New Testament we have today is in a letter from Athanasius, the Bishop of Alexandria, in 367 AD. That’s over 300 years after Jesus.

The criteria were pretty simple, though:

- Apostolicity: Was it written by an apostle or someone who knew them?

- Orthodoxy: Did it match what the church was already teaching?

- Catholicity: Was it being used by most churches, or just one weird cult in the desert?

Real-World Applications for Today

Understanding the books of the New Testament isn't just for theology students. It gives you a massive amount of cultural literacy. Our legal systems, our literature, and our concepts of human rights are deeply tied to these texts.

📖 Related: Am I Gay Buzzfeed Quizzes and the Quest for Identity Online

If you want to actually understand what’s going on in these pages, stop treating them like a magic book and start treating them like a library.

Identify the Genre First

Don't read Revelation the same way you read the Gospel of Mark. Mark is a narrative; it’s telling a story. Revelation is a dreamscape. Romans is a legal brief. If you read a legal brief like it’s a fairy tale, you’re going to be confused.

Get a Good Study Bible

Seriously. Look for something with "Oxford," "HarperCollins," or "ESV Study" in the title. These contain footnotes that explain the 1st-century context. For instance, when Jesus talks about a "camel going through the eye of a needle," there are several theories about what that meant geographically and linguistically. A study Bible keeps you from making up your own weird interpretations.

Read in Context

Taking one verse out of a letter and sticking it on a coffee mug is fine for inspiration, but it usually ignores what the author was actually saying. Read the whole chapter. Read the whole book. If you read 1 Corinthians as a whole, you realize it’s not just a beautiful poem about love (Chapter 13); it’s a blistering rebuke of a church that was acting like a dumpster fire.

Next Steps for Exploration

Start by reading the Gospel of Mark in one sitting. It only takes about 90 minutes. It’s fast, breathless, and gives you the core story without the long genealogies or complex sermons found in Matthew or John. From there, move to the book of Acts to see how the early "startup" phase of the church looked. Finally, pick one short letter—like Philippians—to see how those early beliefs actually affected someone’s daily life in a prison cell.

This approach turns a daunting religious text into a manageable, historically grounded project. You don't have to be a believer to find the historical and literary evolution of these 27 books absolutely staggering.