People think they know the Bible. Most folks imagine a single, thick book with gold-edged pages that fell out of the sky in one piece. Honestly? It’s not even a "book" in the way we think of one. It’s a library. A messy, complicated, ancient library written by about 40 different authors over 1,500 years. If you’re trying to understand the books of the Bible, you’ve got to stop looking at it as a novel and start seeing it as a collection of legal documents, poetry, gritty history, and private letters.

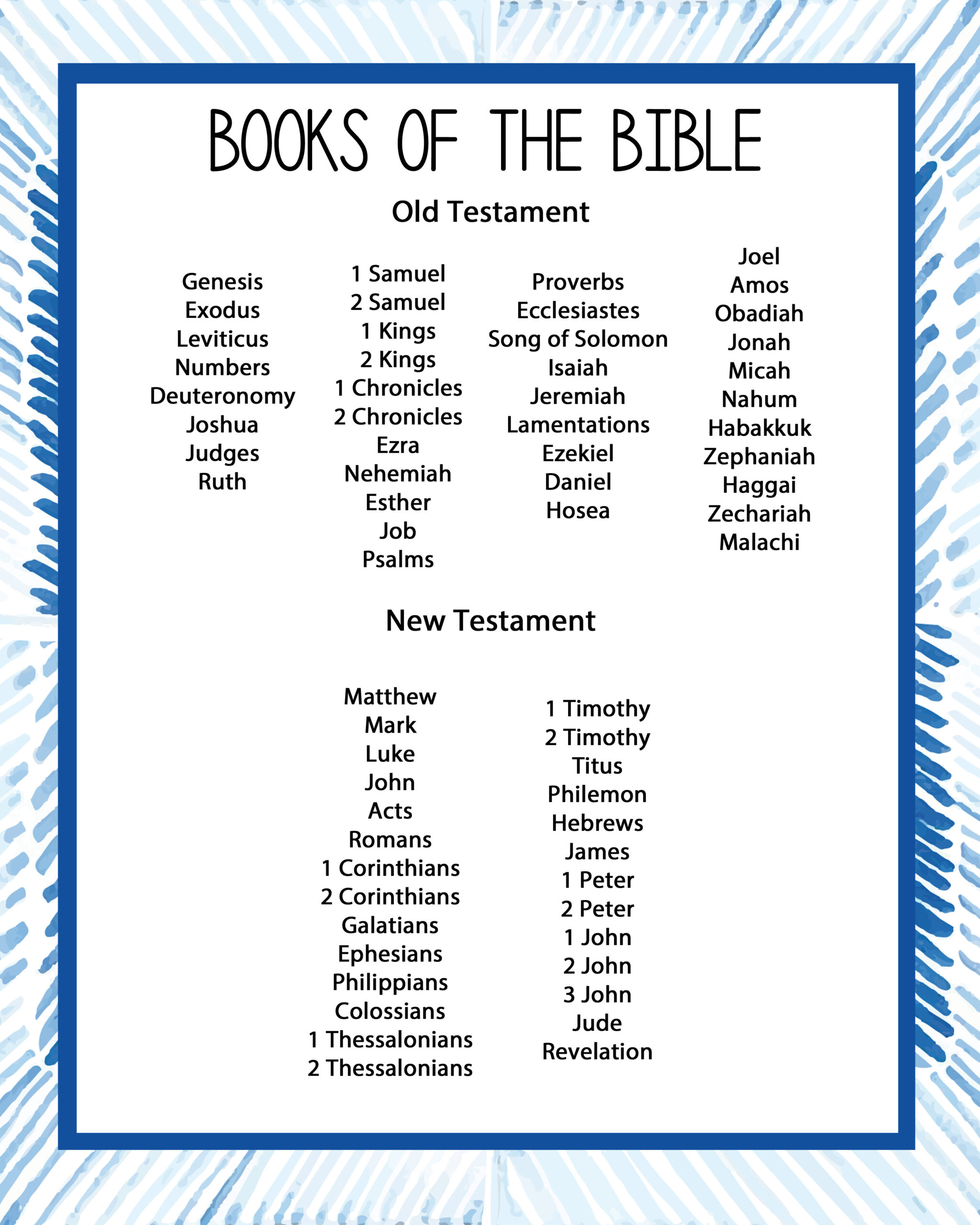

It's wild when you think about it. You’ve got kings, fishermen, a doctor, and even a tax collector all contributing to this thing. They weren't sitting in a room together. They didn't have a group chat. Yet, somehow, these 66 separate pieces (or 73 if you’re Catholic) manage to tell one cohesive story. It's kinda like a massive puzzle where the pieces were scattered across different continents and centuries.

The Old Testament Is Not Just "Old"

The first section—the Hebrew Bible—is basically the foundation for everything. Without it, the New Testament makes zero sense. You have the Torah, or the Pentateuch, which is the first five books. People usually get bored in Leviticus because of all the laws about mildew and goats, but for the ancient Israelites, those laws were a blueprint for a brand new society. They were trying to be different from the empires around them.

Then you hit the historical books. This is where things get cinematic. Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings—it’s full of civil war, assassination plots, and massive failures. If you think the Bible is just "nice stories for kids," you clearly haven’t read about the era of the Judges. It's R-rated. It’s dark. It shows humanity at its absolute worst.

✨ Don't miss: Green Emerald Day Massage: Why Your Body Actually Needs This Specific Therapy

Wisdom and the Weirdness of Ecclesiastes

The Wisdom literature is a total shift in tone. You have the Psalms, which are basically ancient song lyrics. Some are happy; a lot are actually pretty depressed. Then there's Ecclesiastes. If you're feeling cynical about life, that's your book. The author basically says, "Everything is meaningless, we all die, so just enjoy your bread and wine." It's shockingly modern for something written thousands of years ago. It doesn't offer easy answers. It sits in the tension of life being unfair.

Why the Order of Books of the Bible Actually Matters

Most people read the Bible from left to right, like a novel. Big mistake. The order we see in most English Bibles today (Genesis to Revelation) is based on the Latin Vulgate, not necessarily the chronological order in which things happened. For example, the book of Job might actually be one of the oldest stories, but it’s tucked away in the middle.

In the Hebrew tradition, the order is different. They call it the Tanakh. It ends with 2 Chronicles, which focuses on the hope of returning home. In the Christian Bible, the Old Testament ends with Malachi, which points forward to a coming "messenger." This isn't just a formatting choice. It changes the "vibe" of the ending. One ends with a return; the other ends with a "to be continued."

🔗 Read more: The Recipe Marble Pound Cake Secrets Professional Bakers Don't Usually Share

The Prophetic Literature

Prophecy isn't just about predicting the future. That’s a common misconception. Most of what the prophets like Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Amos were doing was "forth-telling," not "fore-telling." They were social critics. They were yelling at the rich for stepping on the poor. They were calling out corrupt politicians. Sure, they talked about the future, but they were mostly concerned with the mess happening right in front of them.

The New Testament: Letters and Logic

When you jump into the New Testament, the books of the Bible take a turn toward the personal. You start with the four Gospels—Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. They’re like four different witnesses to a car accident. They don't agree on every tiny detail, but they agree on the big picture. Mark is fast-paced. He uses the word "immediately" constantly. Luke is a historian, very detailed. John is the philosopher, getting into the deep "why" behind it all.

Paul’s Inbox

Then you have the Epistles. These are literally just mail. Paul, an early church leader, was writing to small groups of people in cities like Rome, Corinth, and Ephesus. These weren't meant to be "holy scripture" at the exact moment he wrote them; they were troubleshooting guides. People were arguing about food, sex, and money. Paul was trying to keep the peace.

💡 You might also like: Why the Man Black Hair Blue Eyes Combo is So Rare (and the Genetics Behind It)

If you read 1 Corinthians, it’s not just a beautiful poem about love used at weddings. It’s a stern letter to a group of people who were being incredibly chaotic and selfish. Reading these books without knowing the "drama" behind the scenes is like listening to one side of a phone call. You have to piece together what the other people were doing to understand why Paul was so frustrated.

Translation Wars and the Language Gap

Let's talk about the elephant in the room: translation. The Bible wasn't written in King James English. It was written in ancient Hebrew, Aramaic, and Koine Greek. Every time you read it, you’re reading an interpretation. Some versions, like the NASB, try to be "word-for-word." Others, like the NLT, go for "thought-for-thought."

There's no such thing as a "perfect" translation. Languages don't map onto each other perfectly. The Greek word "agape" (a type of love) doesn't have a direct English equivalent that captures the full depth. Scholars like N.T. Wright or the late Bruce Metzger have spent their entire lives debating these nuances. It’s a deep well.

Actionable Steps for Exploring the Library

If you actually want to get a handle on this, don't start at page one and try to power through to the end. You'll probably get stuck in the genealogies or the tabernacle dimensions.

- Start with Mark. It’s the shortest Gospel and gets straight to the point.

- Get a Study Bible. Look for one with notes from reputable scholars (The ESV Study Bible or the HarperCollins Study Bible are solid choices). You need the historical context to understand why someone is talking about "clean" and "unclean" animals.

- Use the "Bible Project" videos. They’re free and do a killer job of visualizing the structure of each book. It helps to see the "map" before you enter the woods.

- Compare versions. Read a passage in the NIV and then check the NRSV. The differences in wording often highlight the complexity of the original text.

- Ignore the verse numbers occasionally. Those were added much later (around the 13th to 16th centuries) to help people find things. Sometimes they actually break up the flow of a thought right in the middle of a sentence.

The Bible isn't a monolith. It’s a conversation. It’s a collection of voices that have shaped Western civilization more than any other text. Whether you see it as sacred scripture or just a foundational piece of literature, understanding the individual books of the Bible—their genres, their authors, and their original audiences—is the only way to actually understand the message they're trying to convey. It's a lot of work, but honestly, it’s worth the effort to see the big picture.