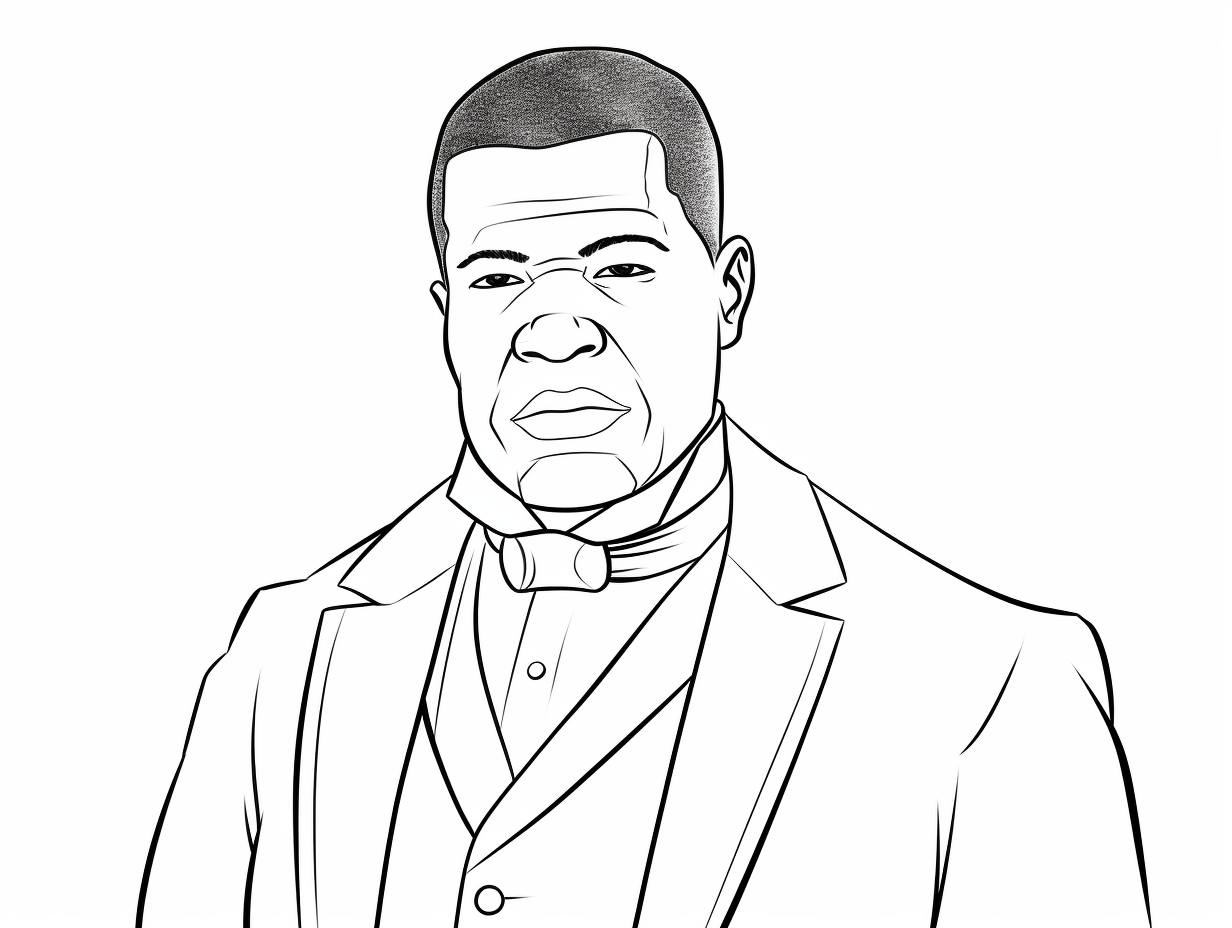

History has a funny way of flattening people into stone. We see the stiff collars, the unblinking stares in sepia, and the dusty pages of Up From Slavery, and we think we know the man. But seeing Booker T. Washington in color for the first time? It changes the vibe. Completely.

Honestly, when you look at the colorized archives from the Library of Congress or the stunning restorations floating around Reddit’s historical communities, you stop seeing a "historical figure" and start seeing a guy who was stressed, ambitious, and incredibly tactical. You see the reddish tint in his hair. You see the intensity in his gray eyes—eyes that had to navigate the deadliest era of American race relations while keeping a literal empire at Tuskegee afloat.

The Visual Shock of Booker T. Washington in Color

Most of us grew up with the black-and-white version of the "Great Accommodator." It makes him feel distant. Safe. Maybe even a little boring. But colorization brings back the grit.

Take the famous 1906 photo of him in his office at Tuskegee. In black and white, it’s a standard portrait of a Victorian-era professional. In color, the room warms up. You see the rich wood of his desk. You notice the stack of papers that probably represent the thousands of letters he wrote to white philanthropists like Andrew Carnegie and Julius Rosenwald. It reminds you that this wasn't just a philosopher; he was a CEO. He was running a massive machine.

He wasn't just "black." His father was white, and his mother, Jane, was enslaved. In colorized photos, his "mulatto" features—as they were called then—become more apparent. You see the nuances of his skin tone that played a massive, unspoken role in how he was perceived by both white donors and the Black community he led.

What the History Books Kinda Gloss Over

People love to pit him against W.E.B. Du Bois. It’s the classic "Accommodation vs. Agitation" debate. But looking at Booker T. Washington in color helps you realize how much of a tightrope he was walking.

✨ Don't miss: How to Sign Someone Up for Scientology: What Actually Happens and What You Need to Know

He lived in a world of red. Red summer lynchings. Red dirt roads in Alabama.

While he was publicly telling Black folks to "cast down your bucket where you are" and basically play nice with segregation, he was secretly funnelling money into court cases to fight that very same segregation. He was a master of the "double game."

- The Public Persona: The humble educator in a gray wool suit who didn't want to rock the boat.

- The Private Reality: A political "boss" who used the "Tuskegee Machine" to reward friends and crush enemies in the Black press.

He once spent a year and a half as a houseboy for a mine owner’s wife. That’s where he obsessed over cleanliness and "the gospel of the toothbrush." To him, a clean collar and a trade were armor. If you looked "civilized" and made yourself indispensable to the local economy, maybe—just maybe—the mob wouldn't burn your house down.

Why the Color Matters for Gen Z and Beyond

There's a reason teachers are using "Booker T. Washington in Color" worksheets and digital art projects. Black history isn't a museum exhibit; it's a living thing. When a student colors in his portrait, they have to decide: what shade was his coat? How bright was the Alabama sun behind him?

It forces a connection.

🔗 Read more: Wire brush for cleaning: What most people get wrong about choosing the right bristles

We’re talking about a man who walked 500 miles to get to Hampton Institute. He showed up with 50 cents in his pocket. He slept under a wooden sidewalk in Richmond just to make it. That’s not a "historical fact." That’s a survival story.

Seeing the dirt on his shoes in a colorized outdoor shot makes that 500-mile walk feel real. It wasn't a metaphorical journey. It was a dusty, exhausting, dangerous reality.

The Myths vs. The Man

Let’s be real about a few things.

- He wasn't a "sellout." He was a pragmatist. He lived through the "Nadir" of American race relations. Between 1890 and 1915, things were arguably worse than they were right after the Civil War. He was trying to keep people alive.

- He didn't hate the arts. People think Tuskegee was only about bricks and farming. While he pushed vocational training, he also built a world-class campus with a chapel and a library. He wanted "dignity," not just a paycheck.

- The 1856 "Mystery." He actually didn't know his exact birthday. Most historians agree on April 5, 1856, but in his mind, he was a man who literally created himself from nothing—even his own name.

The Actionable Takeaway: How to "See" History Differently

If you want to truly understand the legacy of someone like Washington, you can't just read the Wikipedia summary. You've got to look at the visual evidence.

Start by searching for the Library of Congress’s "Frances Benjamin Johnston" collection. She took some of the most intimate photos of Tuskegee life. Use a high-quality colorization tool or look for professional restorations by artists who specialize in skin tone accuracy.

💡 You might also like: Images of Thanksgiving Holiday: What Most People Get Wrong

When you see the sweat on a student's brow at the Tuskegee brick kiln in full color, Washington’s philosophy suddenly makes sense. It wasn't about "liking" manual labor. It was about building a world with your own two hands because no one else was going to give you the keys.

Next time you see a grainy photo of a historical figure, try to imagine the color of the sky that day. It sounds cheesy, but it’s the only way to stop them from being statues and start seeing them as people who were just as complicated and conflicted as we are.

His life was a series of impossible choices. Seeing Booker T. Washington in color won't give you all the answers, but it'll definitely make you ask better questions.

To get a better sense of his actual voice beyond the photos, read the "Atlanta Compromise" speech but imagine it being delivered to a crowd that was actively hostile. It changes everything. You can also find high-resolution digital archives through the National Museum of African American History and Culture that show the actual textures of the tools and clothes he championed.

The real lesson of Washington isn't "work hard." It's "survive and build." That's a message that never loses its color.

Next Steps for Your Research:

- View the Archives: Check the Library of Congress digital portal for the Johnston photographs of Tuskegee.

- Read the Secret Letters: Look into Louis R. Harlan’s "The Booker T. Washington Papers" to see the "secret" side of his activism.

- Visit the Site: If you're ever in Alabama, go to "The Oaks." Standing in his actual home makes the transition from black-and-white to color permanent in your mind.