Ever looked at a medical scan of your own barking dogs and wondered why it looks like a pile of spilled dominoes? You aren't alone. Honestly, most people expect to see a simple structure when they search for bones in the foot images, but what they find is a chaotic, 26-bone jigsaw puzzle that seems way too fragile to hold up a whole human. It's kind of a miracle we can walk at all.

Your foot isn't just a block of calcium. It’s a high-performance suspension system. Each foot contains 26 bones, 33 joints, and over a hundred muscles, tendons, and ligaments. When you look at high-resolution bones in the foot images, you're seeing a masterpiece of evolutionary engineering designed to absorb three times your body weight with every single step you take while running.

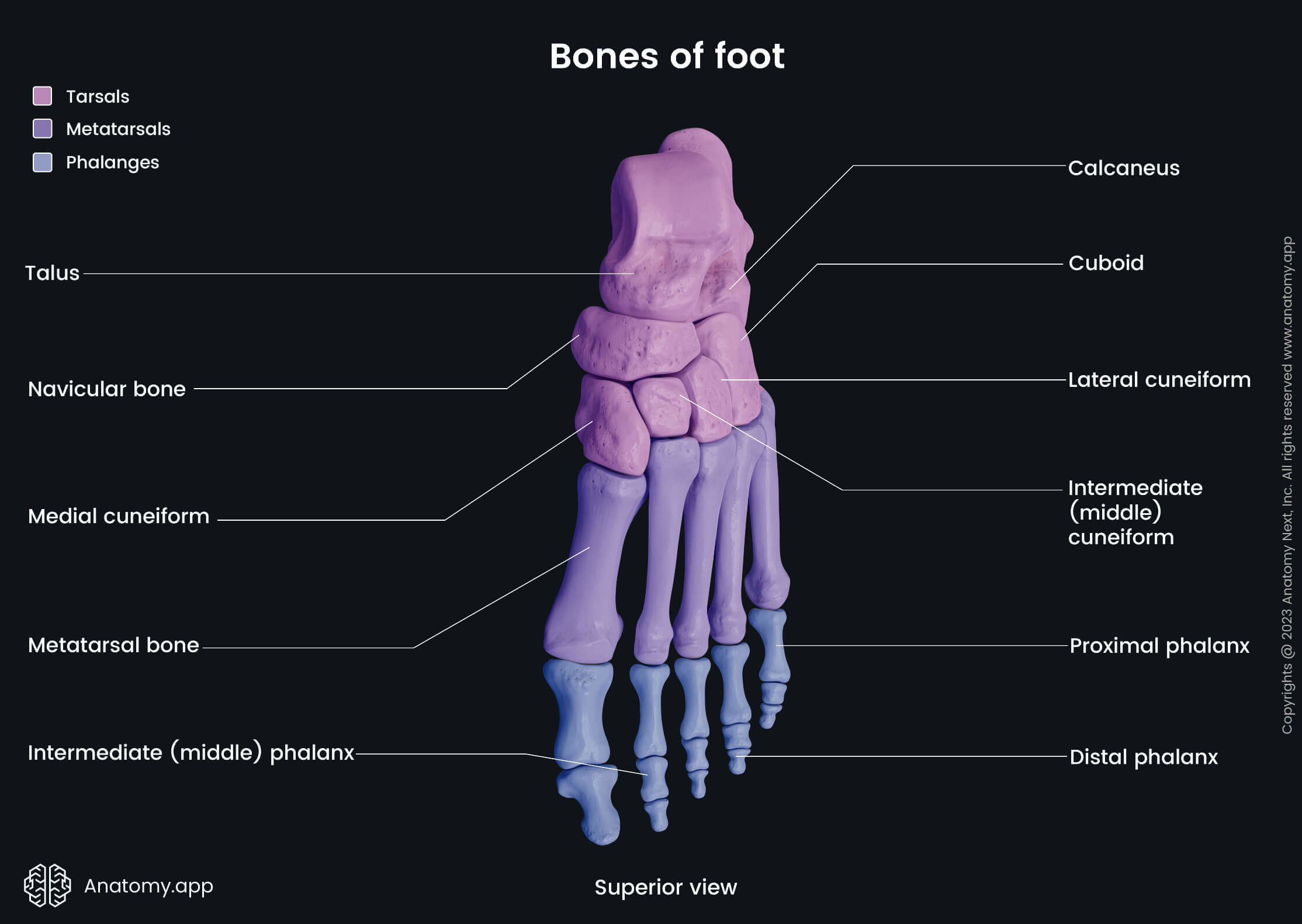

What You're Actually Seeing in Bones in the Foot Images

Most diagrams split the foot into three main zones: the hindfoot, the midfoot, and the forefoot. But that's a bit too sterile. Think of it more like a bridge. The hindfoot and midfoot are the heavy-duty structural supports, while the forefoot is the flexible platform that pushes you off into the world.

✨ Don't miss: Dr Mark Nesselson New York: What Most People Get Wrong

The Hindfoot and Midfoot: The Powerhouse

The "stars" of any lateral view in bones in the foot images are the talus and the calcaneus. The calcaneus is your heel bone. It's the biggest bone in your foot and takes the brunt of the impact when your heel hits the pavement. Sitting right on top of it is the talus. This bone is weird because it doesn’t have any muscles attached to it; it’s basically a lubricated hinge that connects your foot to your leg.

Moving forward, you hit the midfoot. This is where things get crowded. You've got the navicular, the cuboid, and the three cuneiform bones. They form the arch. If you look at an image of a flat foot versus a high arch, you’ll see these bones either stacked tightly or slumped down. When people talk about "collapsed arches," they’re usually talking about the relationship between these specific midfoot bones and the posterior tibial tendon that's supposed to hold them up.

The Forefoot: Where the Action Happens

Then you have the metatarsals. These are the five long bones that lead to your toes. If you've ever had a "stress fracture," it was likely in the second or third metatarsal. They are thinner than you’d think. Finally, the phalanges—your toes. Your big toe (the hallux) only has two bones, while the rest of your toes have three.

Interestingly, there are often two tiny, pea-shaped bones hidden under the big toe joint called sesamoids. They act like pulleys for tendons. In many bones in the foot images, beginners mistake these for bone chips or fractures, but they’re actually supposed to be there.

Common Misinterpretations and Why Context Matters

Looking at a 2D image of a 3D structure is inherently confusing. Doctors use different "views"—AP (front to back), lateral (side), and oblique (angled)—to get the full story. If you're just Googling "foot bone anatomy," you might see a clear, color-coded map. Real X-rays are much messier.

One thing that trips people up is "accessory bones." About 20% of the population has extra little bone bits, like an accessory navicular or an os trigonum. They show up on bones in the foot images as small floaters. Most of the time, they do absolutely nothing. Sometimes, they cause chronic pain. But just because you see an "extra" piece in a photo doesn't mean your foot is broken. It might just be how you were built.

The Problem with Self-Diagnosis via Search

Searching for bones in the foot images because your foot hurts is a double-edged sword. You might find a picture of a Jones fracture—a break at the base of the fifth metatarsal—and convince yourself that's what you have. But a Jones fracture looks remarkably similar to an avulsion fracture or even just a prominent styloid process in a grainy photo.

The nuances are everything. Dr. Casey Humbyrd, an orthopedic surgeon at Penn Medicine, often notes that the physical exam is just as important as the imaging. You can have a "perfect" looking X-ray and still be in agony because of a ligament tear that doesn't show up on a standard bone scan. Conversely, some people have "ugly" X-rays with bone spurs and arthritis but zero pain.

How Age and Activity Change the Picture

A child’s foot image looks like a ghost. Seriously. Because kids are mostly cartilage, their bones appear disconnected or even missing in X-rays. As we age, those "gaps" fill in with solid bone (ossification).

In athletes, the bones actually get denser. Wolff’s Law states that bone grows in response to the stress placed upon it. A marathon runner's metatarsals might look thicker on an image than those of a sedentary office worker. On the flip side, someone with osteoporosis will have "thinner" looking bones in images, appearing more transparent or "ghostly" because the mineral density is lower.

What About Bunions?

If you look at bones in the foot images of a bunion (hallux valgus), it’s not just a "bump" of skin. The actual first metatarsal is drifting outward, and the big toe is leaning inward. It’s a structural misalignment. The image shows the joint partially dislocating over time. Seeing this on a screen usually makes people realize why a "bunion cream" isn't going to fix a bone that's literally pointing the wrong way.

Practical Next Steps for Foot Health

If you’ve been scouring bones in the foot images because of persistent pain, stop squinting at the screen and take these actual steps.

Check your wear patterns. Look at the bottom of your favorite shoes. If the inside edge is worn down significantly more than the outside, your bones are likely collapsing inward (overpronation). This puts massive stress on the midfoot bones you see in those diagrams.

📖 Related: Healthy Food for Weight Loss Recipes: Why Most People Are Still Hungry

Test your mobility. Stand up and try to lift just your big toe while keeping the other four on the ground. Then try to lift the four while keeping the big toe down. If you can't do this, your intrinsic foot muscles are weak, which means your bones are taking more impact than they should.

Consult a professional for imaging. If you have "point tenderness"—meaning you can poke one specific spot on a bone and it hurts sharply—you need a real X-ray. Stress fractures are notorious for not showing up on images until they start healing, which can take two weeks. A podiatrist or orthopedic surgeon might need an MRI or a bone scan to see what a standard photo misses.

Strengthen the platform. Your bones are the frame, but the muscles are the shocks. Simple exercises like "towel curls" (using your toes to scrunch up a towel) or "short foot" exercises can realign how your bones sit under load, potentially fixing the issues you're seeing in those scary-looking medical images.

Don't panic over a weird shape you found on a Google search. The human foot is weird by design. It's a complex, adaptable, and incredibly sturdy piece of equipment that usually just needs the right support and strength to do its job.