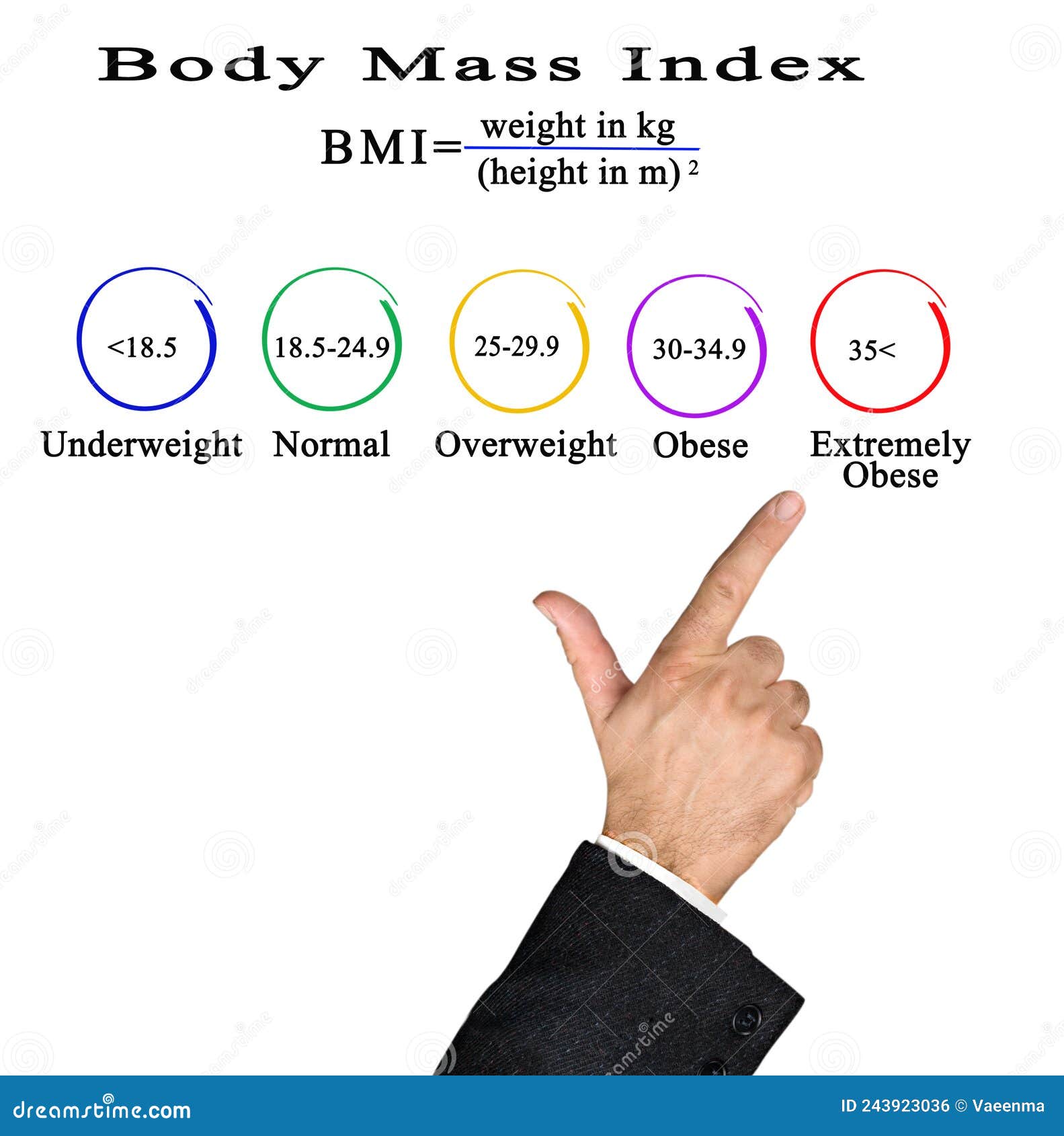

You’ve probably stood on that cold office scale, watched the needle settle, and felt a tiny pit in your stomach while the nurse scribbled a number down. That number leads directly to your BMI. It’s a math equation—weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared—that basically decides how the medical world views your physical existence.

But honestly, the idea of a body mass index healthy range is kinda weird when you think about where it came from.

It wasn't even invented by a doctor.

Adolphe Quetelet, a Belgian mathematician, cooked this up in the 1830s. He wasn't trying to diagnose obesity or heart disease; he was just obsessed with "the average man." He wanted to find a statistical middle ground for the human population. Fast forward nearly two hundred years, and we're still using this mid-19th-century math to determine if someone is "fit" or "at risk." It’s wild.

The Reality of the Body Mass Index Healthy Zone

Most people know the "ideal" bracket is $18.5$ to $24.9$. If you fall into that window, you get a gold star and a lower insurance premium.

Go above $25$, and you're labeled overweight. Hit $30$, and the chart says you're obese.

The problem is that the scale doesn't know the difference between a pound of marbled fat and a pound of dense, functional muscle. I’ve seen athletes—legit professional rugby players and weightlifters—who are technically "obese" according to their BMI. Their hearts are incredibly strong, their blood pressure is perfect, and they can run circles around a "normal" weight person who sits on a couch all day.

Yet, for the average person who isn't a pro athlete, the body mass index healthy range does provide a decent, if blunt, baseline. It’s a starting point. It’s not the whole story, but it’s often the first chapter of your health records that every specialist from your dermatologist to your cardiologist is going to read.

Why Doctors Won't Let It Go

Why do we still use it?

Efficiency.

💡 You might also like: Images of Grief and Loss: Why We Look When It Hurts

It’s incredibly cheap and fast. You don’t need an MRI or a DEXA scan to calculate it. You just need a wall and a scale. In large-scale population studies, BMI actually correlates pretty well with health risks like Type 2 diabetes and hypertension. Research from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) consistently shows that as BMI climbs into the $30$s and $35$s, the statistical likelihood of metabolic syndrome skyrockets.

But statistics are about groups. You are an individual.

The "skinny fat" phenomenon is a perfect example of why the body mass index healthy label can be deceptive. You might have a BMI of $22$—the absolute "sweet spot"—but if you have very little muscle mass and carry all your weight as visceral fat around your internal organs, you might actually be at higher metabolic risk than someone with a BMI of $27$ who hits the gym four times a week.

The Muscle and Bone Factor

Muscle is roughly $18%$ denser than fat. This is where things get messy.

Imagine two people. One is a $5'10"$ software engineer who weighs $195$ lbs. They haven't lifted a weight since high school. The other is a $5'10"$ CrossFit coach who also weighs $195$ lbs. Both have a BMI of $28.0$.

On paper, they are both "overweight."

In reality, their health profiles are worlds apart. The engineer likely has a higher percentage of body fat, while the coach has significantly more lean mass. This is why many experts, including those at the Mayo Clinic, suggest that waist circumference is often a much better predictor of health than BMI alone. If your waist is more than half your height, that’s usually a sign that the fat is sitting in the wrong places, regardless of what the BMI says.

Age and Ethnicity Matter More Than You Think

The "one size fits all" approach to a body mass index healthy score is fundamentally flawed because humans aren't all built from the same blueprint.

Studies have shown that for older adults—those over $65$—having a slightly higher BMI (in the $25$ to $27$ range) might actually be protective. It’s called the "obesity paradox." A little extra reserve can help the body recover from surgeries or long illnesses. If you're $75$ years old and your BMI is $19$, you might actually be more fragile than your neighbor whose BMI is $26$.

📖 Related: Why the Ginger and Lemon Shot Actually Works (And Why It Might Not)

Ethnicity plays a massive role too.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has recognized that for people of Asian descent, the risk for Type 2 diabetes starts at a lower BMI. For these populations, the "healthy" cutoff might actually need to be $23$ instead of $25$. Conversely, some studies suggest that for Black populations, higher BMIs don't always correlate with the same level of metabolic risk seen in Caucasians.

Moving Beyond the Number

If we stop obsessing over the body mass index healthy label, what should we actually look at?

Metabolic health is the real prize here.

You want to know your "Big Five":

- Blood pressure (ideally under $120/80$)

- Fasting blood sugar

- Triglycerides

- HDL cholesterol (the "good" kind)

- Waist circumference

If those five markers are in the green, your BMI is almost irrelevant.

I’ve talked to people who were devastated because their BMI moved from $24.9$ to $25.1$ over the holidays. They felt like they had suddenly become "unhealthy." That’s just not how biology works. Your body doesn't hit a magical "danger switch" the second you cross a decimal point on a chart from the 1800s.

The Psychology of the Scale

We have to talk about the mental toll.

Using BMI as a primary metric can lead to weight bias in healthcare. Some doctors see a high BMI and stop looking for other causes of pain or illness. "Just lose weight," becomes the default prescription for everything from a sore knee to a persistent cough. This can lead to patients avoiding the doctor altogether, which is way more dangerous than being five pounds overweight.

👉 See also: How to Eat Chia Seeds Water: What Most People Get Wrong

Focusing on a body mass index healthy goal can sometimes trigger disordered eating or an unhealthy obsession with the scale. It's much better to focus on "health at every size" principles while acknowledging that carrying significant excess weight does, factually, put strain on the joints and the heart. It’s a delicate balance.

Practical Steps for a Better Health Assessment

Don't throw your scale out the window, but maybe stop giving it so much power over your mood.

If you want a more accurate picture of where you stand, there are better ways to measure progress than just chasing a lower BMI.

- Use a tape measure. Check your waist-to-hip ratio. Take the measurement at the narrowest part of your waist and the widest part of your hips. For men, a ratio of $0.9$ or less is great; for women, $0.85$ or less.

- Track your strength. Can you carry your groceries up three flights of stairs without feeling like your lungs are on fire? Can you do a plank for $60$ seconds? Functional fitness is a much better indicator of longevity than a BMI of $21$.

- Get a DEXA scan or use smart scales. While consumer smart scales aren't $100%$ accurate, they give you a trend of your body fat percentage versus muscle mass.

- Check your bloodwork. Ask your doctor for a full metabolic panel. If your labs are perfect, stop stressing about the "overweight" label on your chart.

How to Talk to Your Doctor

The next time your physician mentions your BMI, you've got every right to ask for more context.

Ask them: "Given my muscle mass and my current activity level, how much weight does this BMI number actually carry in my overall health assessment?"

A good doctor will look at the whole picture. They’ll look at your sleep quality, your stress levels, your diet, and your genetics. They won't just look at a height-to-weight ratio and call it a day.

The body mass index healthy range is a tool—a very old, very blunt tool. It’s like using a chainsaw to prune a bonsai tree. It might get the job done eventually, but it lacks the precision needed for the complex, beautiful, and individual nature of the human body.

Final Actionable Steps

- Prioritize protein and resistance training. Building muscle will improve your metabolic health even if the number on the scale—and your BMI—stays exactly the same.

- Walk more. Aiming for $8,000$ steps a day has a massive impact on cardiovascular health that isn't always reflected in a weight change.

- Sleep 7-9 hours. Lack of sleep wreaks havoc on the hormones that regulate hunger (ghrelin) and fullness (leptin), making it nearly impossible to maintain a healthy weight anyway.

- Stop the shame. If your BMI is high, use it as a data point, not a character judgment. Focus on adding healthy behaviors rather than just subtracting calories.

Ultimately, your health is a mosaic of a thousand different factors. Your BMI is just one tiny, somewhat dusty tile in that entire picture. Look at the whole image instead.