John Hammond was a legend. He'd discovered Billie Holiday and Count Basie. But when he walked into Columbia Records' studios in November 1961 with a scruffy kid from Minnesota who sounded like a rusty gate, people thought he'd finally lost his mind. They literally called the kid "Hammond’s Folly." That kid was Bob Dylan. He was twenty.

If you listen to Bob Dylan's first album today, you aren't hearing the "Voice of a Generation." Not yet. You’re hearing a guy who is desperately trying to sound like a seventy-year-old bluesman from the Mississippi Delta while sitting in a sterile New York recording booth. It’s weird. It’s abrasive. Honestly, it’s kind of a miracle it ever got released at all.

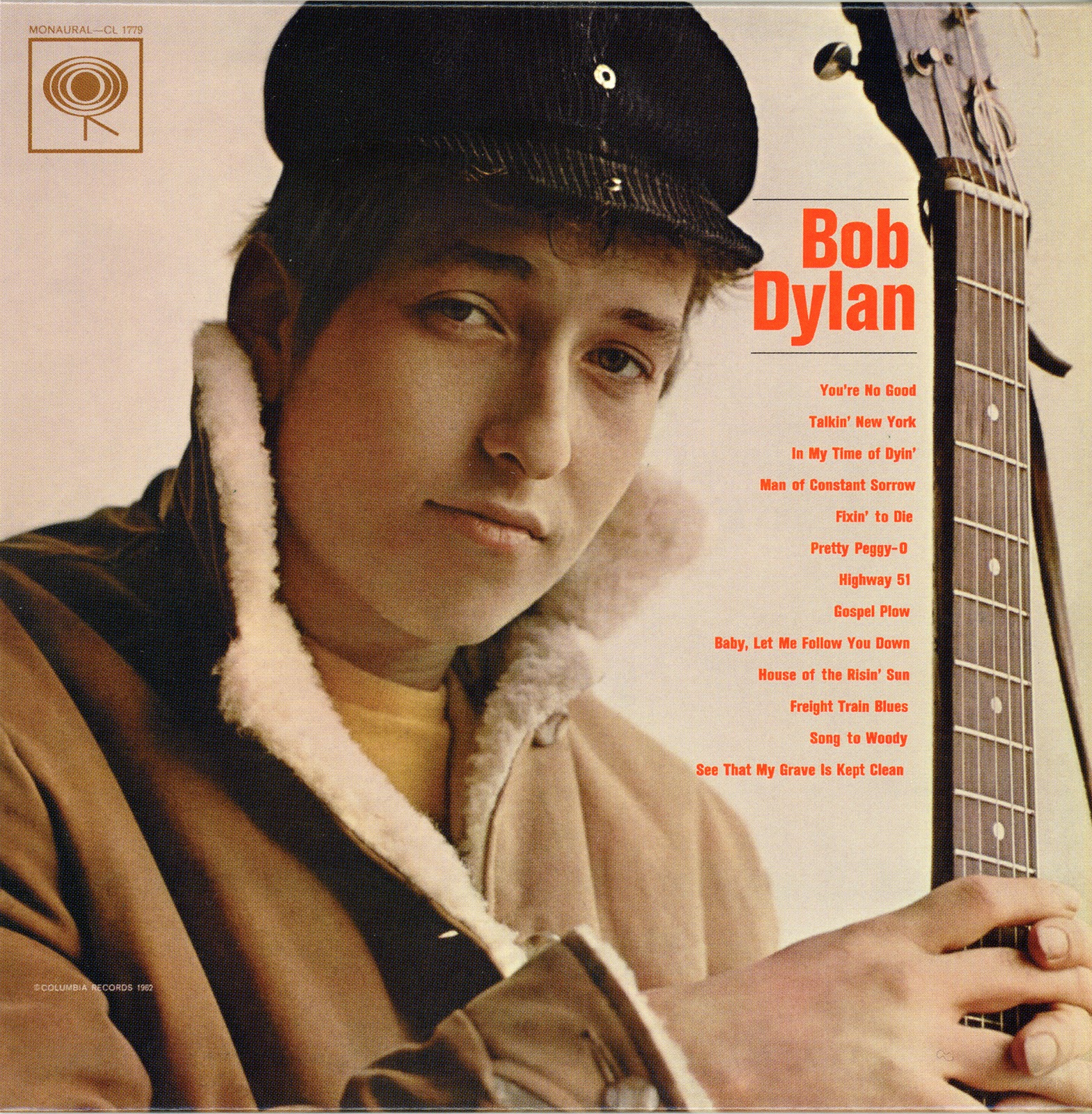

Most people think Dylan exploded onto the scene with "Blowin' in the Wind." He didn't. His self-titled debut was a commercial dud that moved maybe 2,500 copies in its first year. Columbia executives were ready to drop him. They didn't see a folk icon; they saw a weirdo with a harmonica rack who couldn't sing "correctly." But looking back, that 1962 release is the DNA for everything that followed. It’s the raw, unpolished proof that Dylan wasn't interested in being pretty.

The Two-Day Blitz That Cost $402

Recording an album now takes months. Sometimes years. This thing took two afternoons.

Hammond booked the studio for November 20 and 22, 1961. Dylan showed up, spit out about seventeen songs, and they picked thirteen. Total cost? Roughly $402. That’s it. There were no retakes for "perfection." If Dylan made a mistake, he usually just kept going. You can hear it in the tracks—the way the guitar strings buzz, the way he catches his breath. It’s visceral.

The tracklist is mostly covers. That’s the big surprise for people who only know Dylan as a songwriter. Out of thirteen songs, only two were originals: "Talkin' New York" and "Song to Woody." The rest were traditional folk, blues, and gospel tunes. He was basically doing a high-speed tour of his record collection.

- "You’re No Good" (Jesse Fuller)

- "Fixin’ to Die" (Bukka White)

- "Highway 51" (Curtis Jones)

- "In My Time of Dyin’" (Traditional)

He was obsessed with Woody Guthrie. Like, scary obsessed. "Song to Woody" is a direct tribute to his hero, who was dying in a New Jersey hospital at the time. It’s arguably the most "honest" moment on the record. He sounds less like he's putting on a mask and more like a kid saying thank you to his idol.

The Voice That Divided New York

Dylan’s voice on this record is... a choice.

It’s a nasal, raspy bark. If you grew up on the smooth harmonies of The Kingston Trio or Peter, Paul and Mary—which was the "folk" sound of 1962—Dylan sounded like a train wreck. He wasn't trying to be "folk-pop." He was trying to channel the "Old, Weird America" that Greil Marcus famously wrote about years later. He wanted to sound like the field recordings found on the Anthology of American Folk Music.

Critics were baffled. Some saw the genius. Robert Shelton of the New York Times had already hyped him up after a show at Gerde’s Folk City, which helped get him the Columbia deal. But the general public? They just didn't get it. Why listen to a kid pretend to be an old man when you could listen to actual old men?

Why "Bob Dylan" Failed (And Why That Matters)

The album peaked at exactly nowhere on the charts in the US. It didn't even touch the Billboard 200.

In the industry, it was a joke. Hammond had to fight tooth and nail to keep Dylan on the label. If it weren't for Johnny Cash—who was Columbia’s big star—telling the suits to back off and leave the kid alone, Dylan might have been a one-hit-wonder who never actually had a hit. Cash saw something the accountants didn't. He saw the "freight train" energy.

The failure of Bob Dylan's first album actually gave him a weird kind of freedom. Because he wasn't an instant pop star, he didn't have to keep repeating a formula. He went back to the Village, kept writing, and by the time he went into the studio for his second album, he had "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall" ready to go. The debut was the clearing of the throat.

The "Stolen" Arrangements

There’s a bit of drama involved with this record, too. Specifically regarding "House of the Risin' Sun."

Dylan learned the arrangement from Dave Van Ronk, the "Mayor of MacDougal Street." Van Ronk was planning to record it for his own album. Dylan asked if he could use it. Van Ronk said no. Dylan recorded it anyway.

✨ Don't miss: Why Insane Clown Posse Miracles Became the Internet's Favorite Punchline (and What Everyone Missed)

It caused a huge rift in the tight-knit Greenwich Village folk scene. For a while, Van Ronk couldn't even play his own signature song because everyone thought he was covering Bob Dylan. It was the first sign of Dylan’s ruthless streak—his willingness to take whatever he needed for his art, regardless of whose toes he stepped on. He was a sponge, but a sponge with sharp edges.

Breaking Down the Standout Tracks

"Talkin' New York" is the first real glimpse of Dylan the storyteller. He talks about arriving in the city with "my guitar in my hand" and getting told he sounds like a "hillbilly." It’s funny. It’s cynical. It’s the foundation for his later "talkin' blues" style.

Then you have "Man of Constant Sorrow." Most people know the George Clooney version from O Brother, Where Art Thou?, but Dylan’s 1962 version is haunting. He uses a dropped tuning that gives the guitar a heavy, percussive thud.

- Freight Train Blues: He hits this high-pitched, sustained note that sounds like a literal steam whistle. It’s impressive, if a bit gimmicky.

- Fixin' to Die: He’s using a slide (possibly a lipstick tube or a pocketknife) to get that Delta blues whine.

- See That My Grave Is Kept Clean: A Blind Lemon Jefferson cover. This is where the "old man" persona is strongest. He’s singing about death and gravestones with the intensity of someone who has seen it all, despite being barely old enough to drink.

The Myth of the "Authentic" Folk Singer

One of the biggest misconceptions about this era is that Dylan was a "natural." He wasn't. He was a highly calculated performer.

He’d spent hours in the New York Public Library looking at old microfilms of newspapers from the 1920s to get "authentic" details for his songs. He changed his name (from Zimmerman). He told reporters he’d run away and joined the circus. He was building a character. Bob Dylan's first album is the first official document of that character.

It’s not an "honest" album in the sense of a diary entry. It’s a performance. He was trying on different hats—the bluesman, the hobo, the protest singer—to see which one fit. Ironically, by pretending to be all these other people, he stumbled onto a sound that was entirely his own.

What You Should Do Next

If you want to actually understand Dylan, you can't just skip to Highway 61 Revisited. You have to hear the origin point.

Listen to "Song to Woody" first. It’s the emotional core of the record. Then, immediately listen to his version of "House of the Risin' Sun" and compare it to the famous version by The Animals. You’ll hear how Dylan was stripping the song down to its bones while everyone else was trying to make it a radio hit.

After that, go find a copy of The Freewheelin' Bob Dylan. Listen to the jump in quality between 1962 and 1963. It’s one of the greatest leaps in artistic history. But remember: the second album wouldn't exist without the "folly" of the first.

- Check the credits: Look for the names of the session players (there basically weren't any, it's almost all him).

- Compare the mono vs. stereo mixes: The mono version feels much more "in the room" and is generally preferred by purists.

- Read the liner notes: They were written by "Stacey Williams," which was actually a pseudonym for Robert Shelton. It’s pure 1960s hype-man prose.

The record is a time capsule. It’s New York in the winter of '61. It’s the smell of coffee houses and cigarette smoke. It’s the sound of a kid who was about to change the world, even if the world wasn't quite ready to listen yet.