Martin Scorsese was losing it. Imagine being one of the greatest directors in cinema history, standing backstage at the Winterland Ballroom on Thanksgiving 1976, and realizing your entire movie is about to go up in flames. The reason? A man in a white hat and a polka-dot shirt named Bob Dylan.

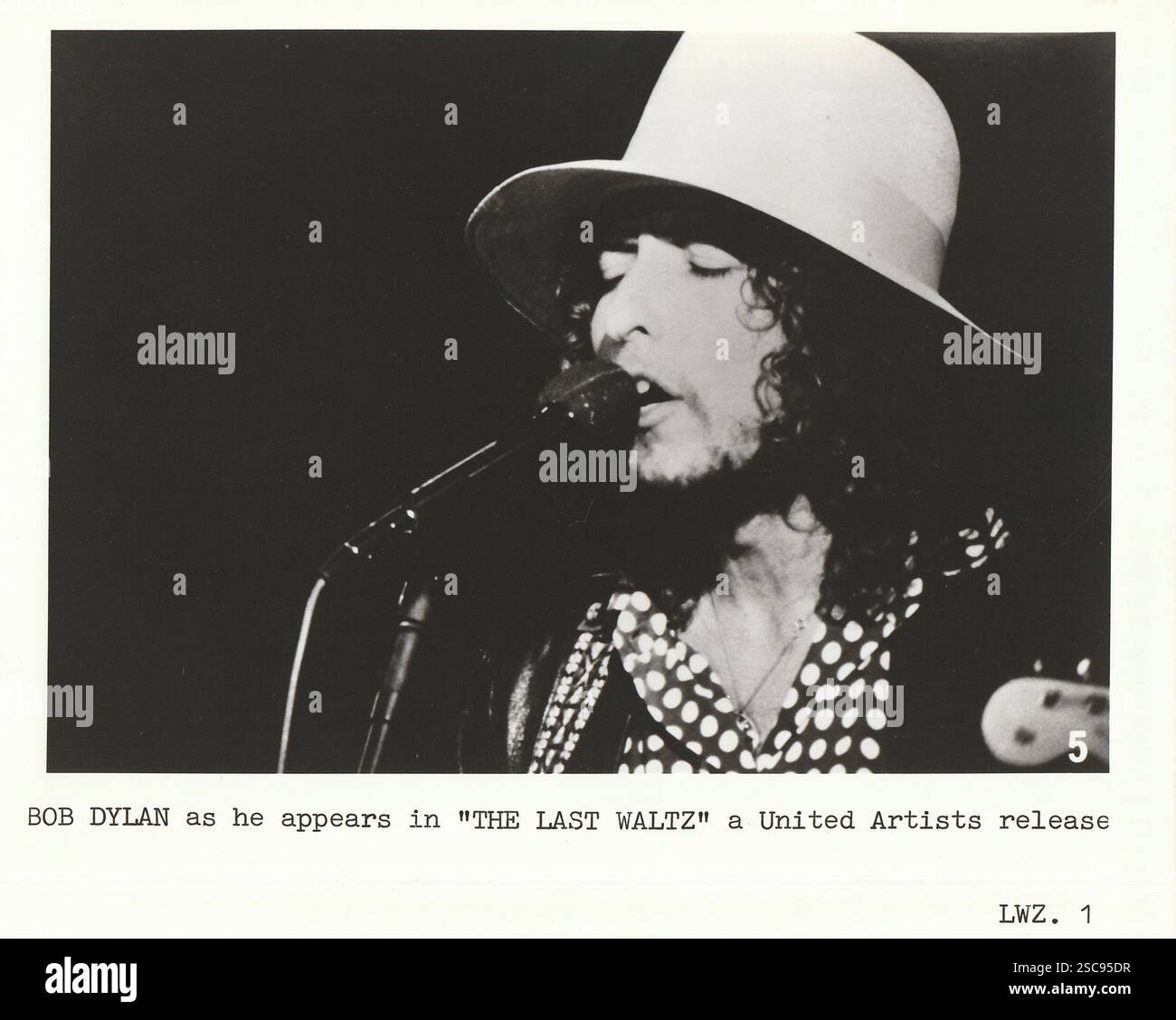

The story of Bob Dylan and The Last Waltz is usually told as a triumph. We see the footage: Dylan taking the stage as the final guest, looking like a street-smart poet-king, leading The Band through a blistering set. It feels inevitable. It feels like the only way that era could have ended.

But behind the scenes, it was a total mess. Honestly, it's a miracle the cameras were even rolling when he walked out.

The $25 Ticket and the Salmon

Let’s set the scene first. This wasn’t just a concert; it was an event. Bill Graham, the legendary promoter, had turned the Winterland into a 19th-century ballroom. He literally took the sets from the San Francisco Opera’s production of La Traviata—huge wooden pillars and crystal chandeliers—to give the place some class.

People paid 25 bucks for a ticket. In 1976, that was insane. Usually, a ticket cost five dollars. But for that price, you got a full turkey dinner and a night of rock royalty.

Dylan even contributed to the menu. Kind of. One of his "handlers" owned an Alaskan fish company, so 400 pounds of salmon were brought in to make sure the vegetarians in the crowd had something to eat. It was a nice gesture, sure, but it didn't mean Dylan was going to make the filming easy.

The 15-Minute Crisis

Warner Brothers had bankrolled the movie on one condition: Dylan had to be in it. No Dylan, no deal. No deal, no money for Scorsese or Robbie Robertson.

Dylan showed up. That wasn't the problem. He’d even rehearsed with The Band in a private hotel room because he didn't want to do the formal dress rehearsal at the venue. But about fifteen minutes before he was supposed to go on stage, his lawyer walked out of the dressing room with a look that basically said "everyone is screwed."

✨ Don't miss: How to Watch the Order of the Dark Knight Trilogy Without Getting Confused

Dylan didn't want to be filmed.

He was worried that Scorsese’s movie would compete with his own project, Renaldo and Clara, which he was directing himself. He didn't want his face on two different movie posters at the same time. Scorsese went into a full-blown panic. If the cameras didn't roll for Dylan, the studio might pull the funding for everything they’d already shot.

How Bill Graham Saved the Movie

Scorsese didn't fix it. Robbie Robertson didn't fix it. It was Bill Graham who finally cracked the code.

Graham charged into Dylan’s dressing room. He didn't use soft words. He basically told Dylan that if he didn't let them film, it would ruin his friends in The Band. Eventually, they reached a weird, last-minute compromise. Dylan agreed to let them film his last two songs only.

This is why, if you watch the movie closely, the first few songs of the Dylan set have a different "vibe." During "Baby, Let Me Follow You Down" and "I Don't Believe You (She Acts Like We Never Have Met)," Scorsese was ordered to turn the cameras away. Bill Graham, being Bill Graham, eventually told the camera crews to "screw it" and start filming anyway, but that tension is baked into the very film grain.

The Five-Song Finale

Dylan’s actual performance was short but heavy. He played:

- Baby, Let Me Follow You Down

- Hazel

- I Don't Believe You (She Acts Like We Never Have Met)

- Forever Young

- Baby, Let Me Follow You Down (Reprise)

He looked electric. This was the Dylan of the Desire era—voice sharp, eyes hidden under that brimmed hat. When he hit the final notes of the "Baby, Let Me Follow You Down" reprise, it was the signal for the ultimate rock and roll curtain call.

🔗 Read more: Doors the Unknown Soldier: What This Massive Hit Actually Means

"I Shall Be Released"

The true emotional peak of Bob Dylan and The Last Waltz is the finale. Every single guest from the night—Eric Clapton, Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Van Morrison, even Ringo Starr—piled onto that cramped stage.

They sang "I Shall Be Released."

It was a mess. There were too many people and not enough microphones. You can see Ringo in the back just happy to be there. But when Dylan and Richard Manuel shared the vocals on that song, it felt like a funeral and a wedding at the same time. It was the end of a sixteen-year road for The Band, and Dylan, the man who had essentially "hired" them into the stratosphere a decade earlier, was there to turn out the lights.

Why It Still Matters

People still argue about The Last Waltz. Levon Helm, the Band's drummer, famously hated the movie. He thought it was a vanity project for Robbie Robertson and Scorsese. He even pointed out that Robertson’s microphone was turned off for most of the night (which, if you watch the isolated audio tracks, is mostly true).

But even with the drama, the egos, and the "Cocteau Room" (the backstage area filled with enough cocaine to power a small city), the Dylan footage remains the anchor.

If you want to understand why this performance is so vital, don't just watch the movie. Go find the "Complete Last Waltz" recordings. Listen to the version of "Hazel" that didn't make the theatrical cut. It’s raw. It’s less "produced." It shows a group of guys who knew each other's musical habits so well they didn't even need to look at each other to know where the beat was going.

To get the most out of your next viewing or listen:

- Watch the eyes: Notice how Dylan rarely looks at the cameras. He's playing for the guys behind him.

- Listen for the bass: Rick Danko’s work during the Dylan set is some of the most melodic playing of the night.

- Ignore the "Cocaine Booger": Yes, Neil Young had a visible rock of cocaine in his nose that Scorsese had to rotoscope out at great expense. It’s a fun piece of trivia, but the music is better.

The next time you pull up Bob Dylan and The Last Waltz, remember that what you're seeing almost never happened. It was a few minutes away from being a lost moment in history. Instead, it became the gold standard for how to say goodbye.

Check out the 40th-anniversary box set if you can find it. It includes "This Wheel's On Fire," a Dylan/Danko collaboration that was bafflingly left out of the original film but captures the soul of their partnership better than almost anything else.