You’re walking through Manhattan’s Chinatown, maybe down Catherine Street or past the old markets on Broome, and you see it: a yellow metal tag clipped to a chicken’s wing. To the casual tourist, it’s just a piece of plastic or tin. But to anyone who actually knows their way around a Cantonese kitchen or a high-end Michelin-starred restaurant in New York City, that tag is a flag. It’s the calling card of Bo Bo Poultry Market, a business that somehow manages to bridge the massive gap between gritty immigrant traditions and the elite "farm-to-table" movement.

Honestly, it’s a weird success story.

Most people think "live poultry market" and imagine something out of a Dickens novel—cramped cages, feathers flying, and a general sense of chaos. But Bo Bo is different. They’ve basically cornered the market on a specific type of bird that most Americans don't even know exists.

Why the "Buddhist Style" Chicken Actually Matters

If you go to a standard supermarket, you’re buying a bird that was bred to grow so fast its legs can barely support its weight. It’s flavorless. It’s watery. It’s... fine for a nugget, I guess.

Bo Bo Poultry Market doesn't play that game.

They specialize in what they call "Buddhist Style" chickens. Now, don't get it twisted—this isn't just a religious label. In the culinary world, this refers to a bird that is processed with its head and feet still attached.

Why? Because in traditional Chinese cooking, and specifically for prayer or ceremonial offerings, the animal must be whole. It represents a beginning and an end.

But for the home cook who just wants a killer dinner, the head and feet are basically a giant neon sign saying "this bird is fresh." You can’t hide a stale chicken when the eyes are still there. Plus, if you’re making stock, those feet are pure gelatinous gold. If you’re tossing them out, you’re tossing out the soul of your soup.

The Richard Lee Legacy and the 1985 Pivot

The story started back in 1978 when Richard Lee bought an egg farm near the Catskills. By 1985, he realized that the Chinese community in NYC was miserable with the chicken options available. They wanted the birds they remembered from home—leaner, tougher (in a good way), and yellow-skinned.

He opened a market under the Williamsburg Bridge. It was a family affair.

Richard and his brothers didn't just buy random birds; they sought out specific breeds like the Barred Silver Cross. These aren't your typical white-feathered industrial birds. They grow slowly. While a Tyson chicken might be ready for the oven in four weeks, a Bo Bo bird takes its sweet time, often twice as long.

This slow growth lets them actually develop muscle. It changes the chemistry of the meat. When you bite into it, there’s a "snap" to the skin and a depth of flavor that makes a standard grocery store bird taste like wet cardboard.

From a Small Stall to the NYC Powerhouse

By 1998, they outgrew the "small market" vibe. They built a USDA-licensed facility from scratch in East Williamsburg. That was a massive deal.

Most live poultry markets are state-regulated, which means they can only sell to individuals or certain local spots. Having that USDA stamp meant Bo Bo could sell to hotels, big-name restaurants, and wholesalers across state lines.

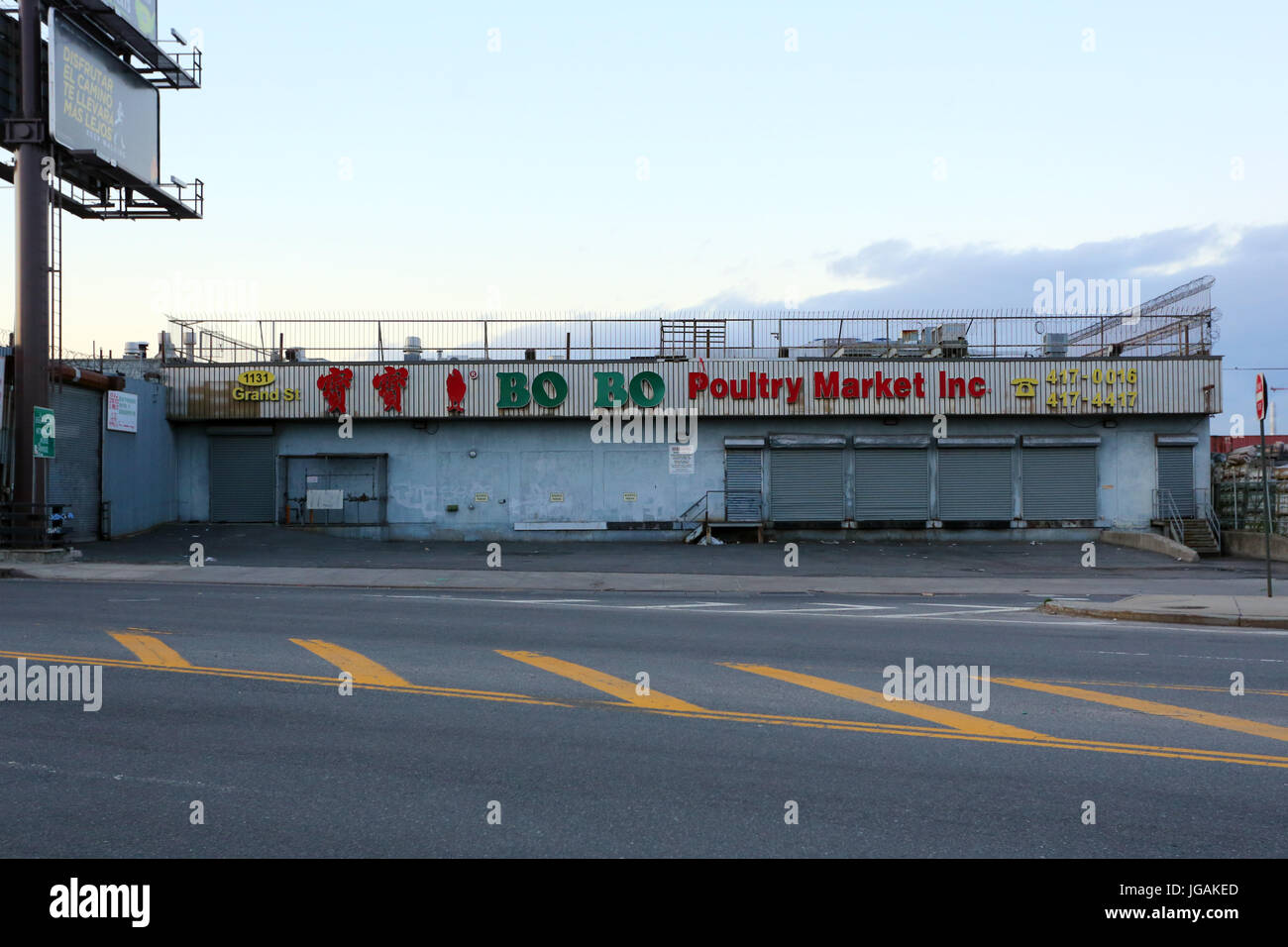

Today, they are located at 1131 Grand Street in Brooklyn. It’s not a retail shop anymore—don't show up there expecting to buy a single bird for lunch. They’ve moved into the world of manufacturing and processing.

Here is the wild part: Despite being a major supplier, they’ve kept their farm network local. We’re talking about dozens of small farms in New York and Pennsylvania, all within about 200 miles of the city.

The "No-Antibiotics" Reality Check

We hear "no antibiotics" and "no hormones" so often it feels like a marketing script. But at Bo Bo Poultry Market, it’s kinda the only way they can do business. Because their birds aren't packed into the high-density "houses" you see in the South, they don't get sick in the same way.

They are free-roaming. Not "pasture-raised" (which means they’re outside eating grass all day), but they have space to walk.

Anita Lee, Richard’s daughter, has been pretty vocal about the middle ground they occupy. They aren't trying to be the $40 organic chicken you find at a boutique butcher in the West Village. They want to be affordable.

Most of their retail customers—the grandmas in Chinatown who have been buying these birds for decades—are often using food stamps. Bo Bo has managed to keep the quality high without making the price elitist.

✨ Don't miss: The Result of a Scandal Going Viral: What Actually Happens to a Brand After the Internet Explodes

What You'll Find if You Go Looking

If you’re hunting for a Bo Bo bird today, you have to look in the coolers of Chinatown markets or specific butchers like Luis Meat Market in the Essex Street Market.

Keep an eye out for these varieties:

- The Classic Bo Bo Chicken: The yellow-skinned staple.

- Poussins: Tiny, tender young chickens.

- Silky Chickens: These are the ones with black skin and bones. They look like something out of a sci-fi movie, but they are prized for medicinal soups.

- Partridges and Quail: Usually seasonal, but they pop up.

The Controversy of the "Wet Market" Label

Let’s address the elephant in the room. During the 2020 pandemic, "wet markets" became a dirty phrase. People started looking at New York’s live poultry markets with a lot of suspicion.

Animal rights groups like PETA have pushed to shut them down, calling them "blood-soaked."

But the reality is more nuanced. These markets are a vital food source for immigrant communities who don't trust the industrial food chain. For many, a Bo Bo chicken is the only way to get meat that hasn't been pumped with saltwater or frozen for six months.

Is it pretty? No. Slaughtering animals never is. But it’s transparent. You see the bird. You know it’s healthy. You see it processed. There’s a level of honesty there that you’ll never find at a supermarket.

How to Actually Cook a Bo Bo Bird

If you manage to snag one, don't treat it like a Butterball turkey. If you roast it at a low temperature for three hours, you’re going to end up with a very expensive piece of leather.

Because these birds have more muscle and less fat, they respond best to "wet" cooking or high-intensity heat.

- The Poach: This is the classic "White Cut Chicken" method. Submerge it in ginger-scented water, bring it to a boil, then turn off the heat and let it steep. The result is silk.

- The Cleaver: You need a heavy knife. Because the head and feet are on, you’re going to have to do some "butchery" at home. Don't be squeamish.

- The Stock: Use the feet. Seriously. The collagen content in a Bo Bo bird's feet will turn your soup into a jelly-like concentrate once it hits the fridge.

Actionable Steps for the Curious Foodie

If you want to experience what the hype is about without getting overwhelmed, here is your game plan:

📖 Related: UK Savings Tax Threshold Breach: What Really Happens When You Earn Too Much Interest

- Visit Chinatown early. Go to the markets on Catherine Street or Mott Street around 8:00 or 9:00 AM. Look for the yellow wing tags in the refrigerated cases.

- Check the tag. Ensure it actually says Bo Bo. Many markets sell "yellow chickens," but they aren't all from the Lee family's network.

- Ask for the "Buddhist Style" if you want the full experience. If you’re nervous about the head, ask the butcher to "clean it" for you. They’ll chop off the extremities in three seconds flat.

- Start with soup. If you’re worried about the texture of the meat being too firm, use it for a long-simmered herbal soup. It’s the best way to extract the flavor without worrying about "chewiness."

Bo Bo Poultry Market isn't just a business; it’s a weirdly resilient piece of New York history. It’s survived gentrification, health scares, and the rise of mega-corporations. It stays successful because it does one thing—chicken—better than almost anyone else in the five boroughs.